Art and science under the microscope

In 1910, Miss Gladys Roberts became one of the first employees of the Australian Institute of Tropical Medicine in Townsville, Queensland. She was employed to illustrate publications and research papers by the institute staff on a casual basis until 1930, depicting parasites and micro organisms as seen through a microscope. Colour plates of her illustrations were published in the ‘Report of the Institute for 1911′, and a copy of that report, open to show one of Gladys’ works, is now on display in the Landmarks gallery at the National Museum.

Born on 12 March 1888, Gladys Roberts was a daughter of George Alexander Roberts, who arrived in Townsville in 1881 and established a successful law practice. In 1884-85, George Roberts purchased a 7.6 hectare property called Kenilworth, and lived there with his family until his death in 1901. [1] The Roberts were a prominent Townsville family, with George Roberts’ son, (George) Vivian Roberts, becoming senior partner of Roberts, Leu and North Solicitors, a long-serving alderman, deputy mayor, and Deputy Vice-Chancellor of James Cook University.

During the early 1880s, George Roberts contributed £10/10/- to the public appeal for the establishment of a grammar school in Townsville, which opened on 16 April 1888. [2] Until then, “Secondary education was not readily available in Townsville; parents wishing their children to receive higher education were forced to send them to boarding school in the south.” [3] Those attending one of the few private schools available were still required to travel to the University of Sydney to sit their examinations.

From 1902 to 1905, Gladys Roberts attended Townsville Grammar School, studying English, Mathematics, History, Geography, Chemistry, Latin, Greek and French. Gladys was awarded prizes in history, geography and English at the 1904 and 1905 school speech days, where she also played roles in theatrical performances. Speaking about the scenes from ‘As You Like It’, in 1904, headmaster P.F. Rowland commented that “Miss Roberts, very successfully got up, gave a clever and amusing sketch; her scene with Wilson as William, being the great success of the evening”. [4]

Today Townsville Grammar School “prides itself on being the oldest co-educational School on the Australian mainland,” but for many years “Mr Hodges, the second headmaster, was very much against co-education and resisted any attempts to enroll more than three or four girls at any one time.” Mr Rowland, headmaster at the time of Gladys’ enrollment, was “on record as saying that he was not supportive of the idea” of co-education, but changed his mind when Miss Effie Hartley was the first female student to be named Dux of Form VI (Year 12) in 1905. [5]

The effect of the academic achievements of both Effie Hartley and Gladys Roberts during 1905 was clear in Rowland’s comments: “It is with sincere regret, too, that the School will say goodbye to Miss Gladys Roberts, whose refining influence has only been second to that of Miss Hartley, and whose work showed a freshness and originality that was often lacking in the work of those who beat her in examinations.” Following the achievements of Gladys Roberts and Effie Hartley, headmaster Rowland “approached the [Grammar School] Trustees and requested that girl enrollments be increased to at least twenty a year.” [6]

After her graduation, Gladys maintained involvement with the activities of Townsville Grammar School. In 1926, the Townsville Daily Bulletin reported that “The artistic fingers and clever design of Miss Gladys Roberts were deciding factors in the distinctive embellishment of the School of Arts on Friday evening for the first annual ball of the old boys of the Townsville Grammar School Association, which was easily the most successful this season, both in attendance and smart-frocking.” [7] Gladys’ attendance at the same annual event was also reported in following years.

Never marrying, Gladys had an active creative and social life in Townsville. She participated in the activities of the School of Arts, including working as a librarian, and spent a year in London studying at the Royal Academy of Arts. It is uncertain how she came to start working at the Institute of Tropical Medicine, but it appears that her creative talents were recognised by director of the institute, Dr Anton Breinl, possibly through a family connection.

The Institute of Tropical Medicine

The study of diseases and health problems which occur within tropical and subtropical regions, became increasingly specialised and located within those geographic regions during the late 1800s and early 1900s. The Australian Institute of Tropical Medicine, the first medical research institute in Australia, was established in Townsville in 1910. Dr Anton Breinl was appointed as the first director the institute, having studied in Prague, worked at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in England and travelled to Brazil for research.

Between 1910 and 1930, more than 90 staff and visiting scholars worked at the institute before it was moved to Sydney. The institute’s young staff became leaders in their fields, publishing hundreds of research papers, articles and books on a variety of medical subjects, including mental health, nutrition and parasitic infections, as studied in the particular conditions of Australia’s tropical north, Papua New Guinea and neighbouring islands. They treated patients, mapped disease patterns, and collected and identified infection-carrying parasites and insects.

Drawing what she saw

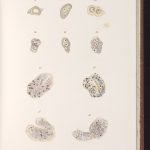

Gladys completed numerous illustrations of specimens collected and analysed by institute staff, as observed under a microscope. She was able to depict the details of human and animal parasitic subjects that were invisible to the naked eye, using her skills as an artist to communicate the research of the institute to other researchers and the general public.

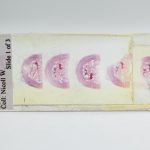

Plates by Gladys Roberts as published in the Australian Institute of Tropical Medicine, Report for the Year 1911 (1912). The plates were printed by Werner and Winter, a printing house in Frankfurt, Germany. National Museum of Australia Research Library.

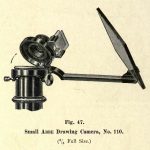

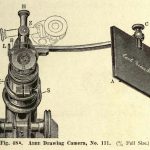

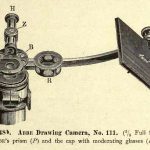

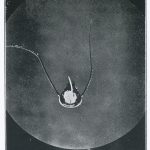

To facilitate her illustration tasks, Gladys used an Abbe ‘camera lucida’, or drawing apparatus, an instrument developed by optical scientist Ernst Abbe, research director and partner at the Zeiss Optical Works, Germany. A number of drawing apparatuses had been developed to aid the work of researchers to illustrate their microscopic work. Most instruments provided a reflected image from the microscope onto a piece of paper allowing the image to be copied. Abbe’s camera lucida consists of an eyepiece housing two prisms and an arm holding a rectangular mirror, attached to the eyepiece of the microscope. When adjusted, the camera lucida allows the user to view the reflected image of the specimen and their pencil on paper through the same eyepiece, so that they do not have to move their eye from the microscope to the paper. Although it made tracing the image of the specimen easier, the technique was reportedly difficult to master.

The National Museum holds over 30 items of historic laboratory equipment used at the Australian Institute of Tropical Medicine in Townsville between 1910 and 1930. The equipment represents two decades of Australian medical research focussed on tropical diseases, vectors of disease, and the diet and lifestyles of human and animal populations in northern Australia.

Unfortunately the National Museum does not hold the Abbe camera lucida used by Gladys Roberts in its collection. Certainly, one or more of the microscopes in collection, would have been used by Gladys during her work for the institute.

A move to photography

At the time of Gladys’ employment at the institute, developments in photographic techniques were beginning to replace hand-drawn illustrations in scientific papers. This change is documented in the publications of the Institute of Tropical Medicine and the National Museum’s collection, which includes a Zeiss photo-micrographic apparatus.

A photo-micrograph is a photograph taken through a microscope, as opposed to a microphotograph which is a very small photograph that requires enlargement. As shown in the photos, the camera was mounted above the microscope, so that the camera used the microscope like a lens. Artificial light was beamed onto the microscope mirror and directed through the specimen and lenses. The microscope was then focused to present a clear image on the plate at the back of the camera.

This photo-micrographic apparatus is likely to date from the mid-1920s, as the institute’s research papers from that time include not only more photo-micrographs, but also those taken by institute staff indicating that they were using their own equipment rather than using photo-micrographs by other researchers to illustrate their work.

Zeiss made a wide range of photo-micrographic apparatus. This version was called the ‘Horizontal and Vertical Camera’ (Horizontal-Vertikalkamera) because, according to the catalogue: “the motion rod of the camera attaches to the base by a hinge. The camera may therefore in the first instance be set up in a vertical position. It may, however, also be folded down for use in the horizontal position.” With some adjustments, this apparatus could also be used to project images from a photograph plate onto a wall or screen.

The 1911 institute report featuring Gladys’ illustrations, laboratory equipment used at the institute, including the photo-micrographic apparatus, and historic slides and specimens are on display in the Townsville exhibit in the Landmarks gallery at the National Museum of Australia.

With thanks to Susan Roberts, Bill Muller at Townsville Grammar School Archives, and the Research Library of the National Museum of Australia.

[1] Families of Townsville (Gallery Services and Townsville City Council, 2016).

[2] ‘Townsville Grammar School’, Townsville Daily Bulletin, 15 October 1938, p12.

[3] Dorothy Gibson-Wilde, Gateway to a Golden Land: Townsville to 1884 (Townsville, Qld; James Cook University of North Queensland, 1985).

[4] Townsville Grammar School magazine and Kim Allen, History of the Townsville Grammar School 1888-1988 (Bowan Hills, Qld; Booralong Publications with Trustees of the Townsville Grammar School, 1990).

[5] TGS Archives newsletter May 2005.

[6] Townsville Grammar School magazine, 1905, as quoted in Kim Allen, History of the Townsville Grammar School 1888-1988 (1990).

[7] ‘Townsville Grammar School Ball’, Townsville Daily Bulletin, 22 June 1926, p6.

Feature image: detail of Plate X, ‘Figure 1 – Microfilaria trichosuri’, by Miss Gladys Roberts, as published in ‘Australian Institute of Tropical Medicine: report for the year 1911’, by Anton Breinl. National Museum of Australia.

Here is a project you might be interested in https://traceybenson.com/2016/09/18/work-in-progess-for-living-green-festival-stage-2-100daysproject/

Thank you Tracey, interesting work developing.