Irresistible forces: reflections on the history of women in Australian science

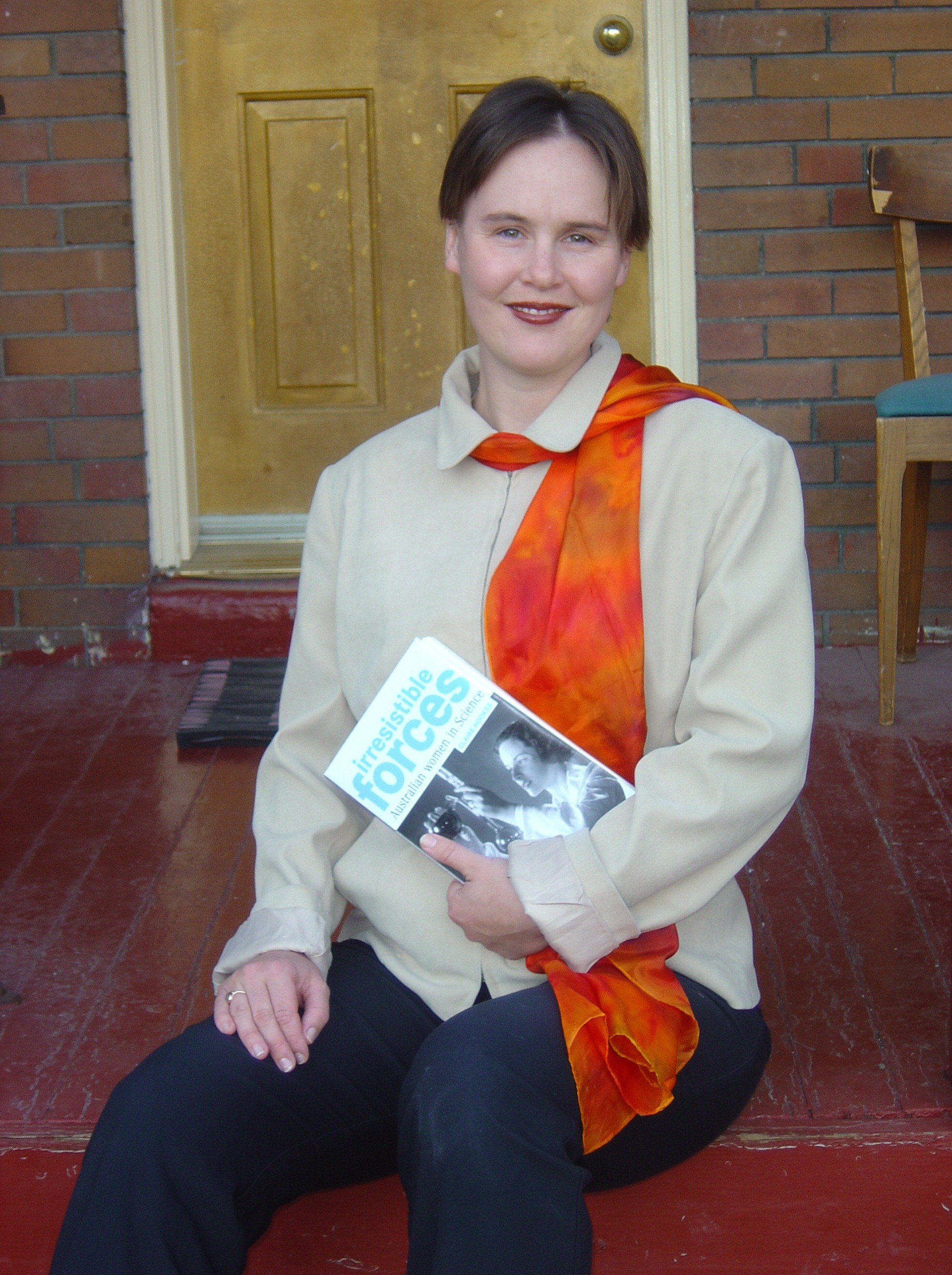

In the early 1990s Claire Hooker began investigating the history of Australian women’s participation in science. In this guest post, she reflects on her research, twenty years on.

Claire is now, as she puts it, ‘not writing about women and science at all anymore!’ She’s a Senior Lecturer in Health & Medical Humanities at the Centre for Values, Ethics & the Law in Medicine (VELiM), at the Sydney School of Public Health. She is also the Leader, Ethics and Politics of Infection Node, at the Marie Bashir Institute for Infectious Disease and Biosecurity (MBI).

We invited Claire to look back on her earlier research as the third post in a series about women scientists connected with the Museum’s participation in the League of Remarkable Women in Science exhibition, which closed yesterday. The other posts, by Kirsten Wehner and Martha Sear, as well as an earlier post about geologist Germaine Joplin, can also be found on this blog. They feature many of the women Claire had studied as part of her work, and we are pleased to be able to share her insights into their lives and careers in the context of contemporary debates about women’s contributions to science.

Here is Claire’s post:

The women scientists from the pre-World War II era, whose implements, publications and images were displayed as part of the League of Remarkable Women in Science exhibition, arouse in me an honouring of their quiet, dedicated sort of nationalism, in which deep connections with land and environment were intermingled with an ethic of humility and service.

I went looking in Australia’s history for women scientists whose lives and careers would refute claims that women’s capacity for spatial and abstract reasoning is less than men’s, due to differences in the development and structure of the brain. If you’re interested in these questions, you may enjoy debates such as this from Harvard University.

But the strange intimacy that arises from peering and prying into the lives of others – reading their letters, looking over their to-do lists, their jottings of household expenses, the neat, beautifully crafted wooden specimen boxes in which Germaine Joplin’s friend and colleague Ida Brown placed carefully hewn rock samples – instead forced on me the realization that these were, in many ways, the wrong questions to be asking. Instead I began to wonder: what counts as, and what makes for, success in science? In Australia, until after World War II there was very little infrastructure for formal scientific research at all – just a handful of people at the handful of universities and museums, many of them engaged desperately in the monumental task of coming to terms with the disorientingly unfamiliar natural landscape in which they lived. Just cataloguing Australia’s unique plants, animals and geology, in order to have enough data to work with to trial and test theories about evolutionary change or ecological shifts, was a tough enough job on its own; and one often carried out by patient and persistent women. Other Australian scientists, then and now, scrambled to apply the newest research from Europe and the USA – which arrived by ship a minimum of six months late, with each expensive journal then passed around social networks of local scientists – to the unique and pressing problems of the developing nation: how best to treat snakebite? Could rain be induced? How can the quality and yield of wheat and wool be improved?

What does it mean to be ‘good’ at science in such circumstances? To the women scientists of the interwar era, it meant simply getting on with the job. These women were direct, honest and practical, and they got a lot done. I still pause, amazed, to consider women’s contribution to mosquito related research. Dr Josephine McKerras and her team dissected around 38,000 of them in search of a better understanding of malaria during World War II – discovering, in the process, what no one had figured out before, which was why mosquitoes breed so poorly in captivity: because they need over a metre of free fall for successful mating. Her colleague Dr Pat Marks described 38 new species in the few decades thereafter. This tediously repetitive fiddly work is, in my view, an outstanding, if unsung, contribution to Australian science.

These women make good role models. They not only coped with, but enjoyed with gusto, the unladylike discomforts of fieldwork – wading out in the flowing tides in the middle of the night to collect specimens, or standing for hours in cold rivers driving core samplers into their beds. The most common description given me – I was told this about every single one of them – by their friends and colleagues was, ‘she didn’t suffer fools gladly’.

To a woman they worked with tireless dedication in the faith that their small contribution to scrupulously considered factual knowledge – say, mapping stratigraphy (the age and layering of the rocks) in NSW or identifying the lifecycle of a nematode (parasite) or cataloguing the distribution of starfish species up and down the eastern seaboard – was a form of service for the common good. It was distressing when this ethic was betrayed in the much less scrupulous ‘real’ world. For example, 40 years later Valerie May was still expressing distress at how her discovery of the cause of mysterious stock deaths – cyanotic algal blooms provoked by fertiliser run-off – was ignored for decades, when instead, preventive measures might have been taken.

Of course not all women scientists were content with the intrinsic rewards of discovery alone. Germaine Joplin’s contemporaries in geology Dorothy Hill, Irene Crespin, Beryl Nasher and Isobel Cookson, wished for, sometimes fought for, and to impressive degree achieved, success as measured by position, pay and promotion, as perhaps more famously, did Ruby Payne-Scott, the physicist who provided the mathematical foundation for the brand new science of radio astronomy in 1945. But whether they worked within an institutional setting or along or outside it, predominantly these women focused on the joy of their work, and on its value, expressed sometimes in the quiet approval of their small band of colleagues. As they slowly gathered their multiple collections of lichens or algae or worms or bivalve shellfish or types of rock, these women were cultivating an intimate feeling for the qualities and processes of the Australian natural environment, and a sense of connection through this to their fellow intellectual travellers around the world

After World War II, Australian governments invested more in scientific research, and as opportunities for research expanded amid a swiftly-changing society, women – who had made up about half of all enrolments in science degrees for some time – began to name and critique some of the subtler forms of sexism that had been there all along. Women scientists today continue to appreciate both the intrinsic rewards of science and the relative autonomy and flexibility that working in research institutions affords – and they continue to need to demand that research institutions do more to shift the structures that produce unequal careers; as you can read in this recent systematic review, there is a long way to go.

In the meantime I hold on to the aspirations of rational judgment and intellectual integrity of which their lives speak so eloquently.

———–

If you’d like to find out more about Claire’s research, you can read her book Irresistible forces: Australian Women in Science, published by Melbourne University Press in 2005.

Like Claire, I found working on the collections of these women scientists inspirational – and also a little intimidating. Their resoluteness in the face of blatantly unfair treatment, years of grinding disappointment or the sudden loss of decades’ worth of meticulous research, was formidable. There were times when I read about their tenacious responses to obstacles and difficulties and I felt not just humbled but small and inadequate in the face of their determination. Germaine Joplin’s decision to retrain by studying at night as a social worker because, despite an international reputation as a petrologist, she couldn’t find more than part-time work as a geology teacher is one example that really sticks in my mind, but there are many more.

Tracing the arcs of the lives of the eight women scientists featured in this exhibition has meant asking myself, over and over: ‘would I have had the mettle to continue through this?’ And if I had, ‘could I have kept my passion and purposefulness so undimmed?’ I’ve stood quietly next to Valerie May’s microscope, or Jean Galbraith’s billy can, and wondered how they did it.

I think Claire gets to the answer here: it’s about a sustaining entwinement of joy with service, and the nourishment that comes from a continuing closeness to the things that fascinate us, and to like-minded people who share our enthusiasms, whether it’s for algae, microscopes, or the history of science.

In the CSIRO Discovery exhibition space, the objects and stories of nineteenth- and twentieth-century women scientists were surround by images and quotes from the women scientists of the twenty-first century, collected by Anne-Sophie Dielen for the League of Remarkable Women in Science project. The quotes were inspirational – and it was clear that they struck a chord with those, especially the schoolgirls, who looked at them. But many visitors also commented in the visitor’s book that they wanted to know more – what work were these women doing? How had they got to where they were? Their questions will be answered in an e-book that Anne-Sophie is putting together from her interviews with more than 40 women scientists around the globe. It will be available later in the year – we’ll keep you posted on its progress.

But those questions are also important ones for us to ask more broadly. After two hours of discussion at a forum connected with the exhibition, ‘Women in Science: Challenges and Solutions’, the consensus seemed to be that now that the more overt barriers to women’s participation had been made visible, attention needed to turn to confronting the subtler – yet just as real – impediments embedded in culture – whether within the sciences themselves, or beyond them.

As both Claire and my colleague Kirsten Wehner have observed, insights from within the humanities – where culture is the subject of the same kind of patient and careful observation these scientists made of sand dunes and slices of granite – may offer a powerful way to understand and address these issues.

What work have women scientists done? How did they do it? What forces shaped their experiences? These are questions the humanities can help to answer.

Given how profoundly getting to know these women scientists, their work and their joys and consolations, continues to shape Claire’s ethos – and, after only a few months, has bolstered and dared mine too – the possibilities seem great.

So, what role do you think exploring the history of women scientists can play in contemporary discussion of increasing women’s participation in scientific research? Let us know your views in the comments section below.

The feature image above shows Dr Germaine Joplin (left) with students on a geology excursion. Image courtesy the Joplin Family.

Reblogged this on VELiM.

Thanks for the reblog!