Women in science – Dr Germaine Joplin

This International Women’s Day (March 8) we’re reflecting on the remarkable achievements of little-known yet talented Australian petrologist Dr Germaine Joplin (1903-1989).

50 years ago women were particularly prominent in the field of geology, yet they struggled to gain recognition and acceptance among their male counterparts. Today, the gender gap is still a concern for Australian science. Leading Australian scientists explored the reasons for this in 2011 in The Conversation. Despite outstanding talent and hard work women scientists experienced prejudice and discrimination in the workplace, if they were lucky enough to gain employment. Determination and a thick skin were prerequisite for any woman then aspiring to a profession in the sciences.

By all accounts, Dr Joplin was a woman who made things happen – for herself, for her chosen field of geology, and for others. Her tenacity and skill saw her make a significant and enduring contribution to the field of geology during the mid-20th century – a time when women, even those with academic achievements which outshone their male peers, struggled to forge careers outside of the home.

On the difficulties of her early research career, Dr Joplin later recalled:

‘When I started in the early [19]20s girls were not supposed to go wandering about with maps and sacks of rocks, but if you were really interested in your work you had to… Girls suffered also in that men on the academic staff took some of the brighter boys on expeditions and the girls missed out. This is why I often took a group with me when I visited a site. Boys and girls studying geology nowadays go on mixed excursions and no-one thinks a thing about it, but once it would have been considered scandalous if a chaperone, usually the professor’s wife, were not invited along also.’[1]

Image courtesy the Joplin Family.

Germaine Joplin was drawn to rocks from a young age. As a child ‘her favourite outing was not to the beach or to the theatre or to the zoo but to the mining museum to look at the rocks’.[2] At school she excelled, winning awards for English, geography, geology and science: ‘Being so good at her subjects every Speech Day she used to be laden down with book prizes’. [3]

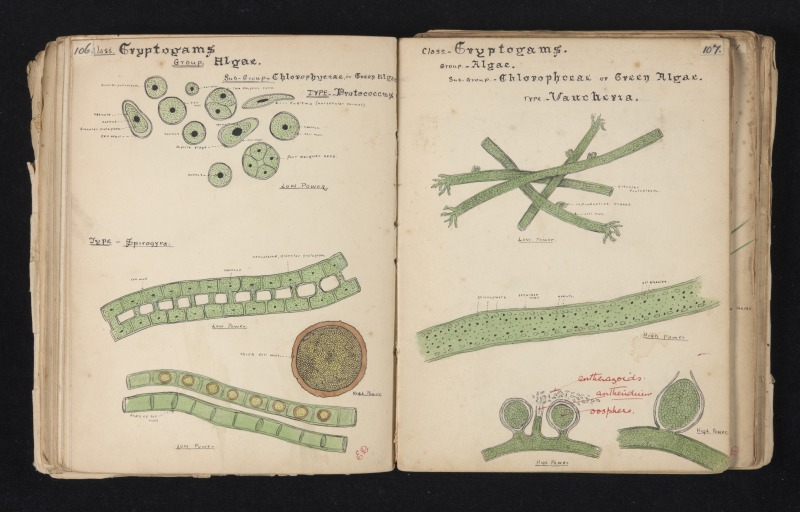

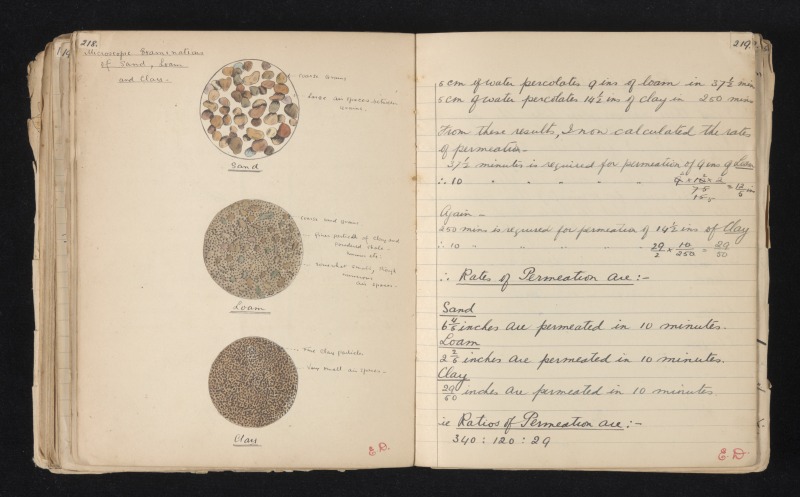

Her mettle was tested when, following iritis, she lost sight in one eye. Her studies for the School Leaving Certificate were put on hold for a year. Undaunted, after recovering she submitted an illustrated exercise book for her final course, ‘Practical Botany’, in 1925. Beautiful coloured drawings of flora, plant cell structures and soil compositions showcased Joplin’s attention to detail and artistic talent – skills she would later use extensively in her work as a geologist. Joplin’s subsequent geology publications featured hundreds of her illustrations – microscopic views of rock samples – still admired for their aesthetic quality and scientific precision in an age when digital cameras have replaced the hand-made.

Image courtesy the Joplin Family.

Image courtesy the Joplin Family.

Success at school allowed Joplin to take up geological studies at university at a time when few women went on to pursue tertiary study. As a student at the University of Sydney, she continued to produce work of exceptional quality, winning ‘virtually every available prize’. [4] Joplin graduated in 1930 with a Bachelor of Science and First Class Honours, the University Medal in Geology, the Science Research Scholarship and the Deas-Thompson Scholarship for Minerology.

Joplin chose to specialise in petrology, an area of geology that studies the origin, composition, distribution and structure of rocks. The branches of petrology correspond to the three different rock types: igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary. Much of Joplin’s research focused on igneous rocks, those formed by the cooling and solidification of volcanic lava.

After graduation Joplin was appointed Curator of the University’s geological museum, demonstrated in geology and continued her research and writing about the Hartley District. Her work gained international recognition when she was awarded the Junior International Fellowship in Science for the year 1933-1934 by the International Federation of University Women. This association aimed to show that ‘women could undertake university work and that it neither destroyed their character or their charm, and that women could hold their own in the professional world.’ [5] The Fellowship allowed Joplin to study petrology under Australian expatriate C.E. Tilley at Cambridge University in the U.K., where she was awarded her PhD in 1935.

Joplin returned to the University of Sydney with a ‘distinguished reputation for her achievements in petrology’ [6] however was only able to take up a temporary position as acting assistant lecturer in geology. Despite the lowly title, Joplin had almost exclusive responsibility for instructing students in igneous and metamorphic petrology. In addition to teaching she continued her research and had papers published in a number of scientific journals.

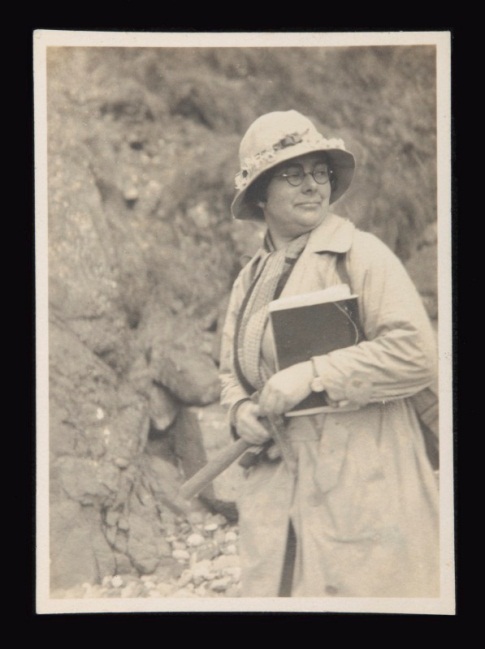

Image courtesy the Joplin Family.

After five years in this position, in 1941 Joplin was awarded a Macleay Fellowship from the Linnean Society of New South Wales which enabled her to conduct petrographic study of the Cooma region in south-eastern New South Wales. This ‘pioneering research’ saw ‘Cooma and its metamorphic style [become] known across the world, described in international textbooks and [become] the basis for much subsequent investigation’, [7] and led, in 1950, to award of a D.Sc. (higher doctorate) from the University of Sydney for her thesis ‘On the question of interaction between primary granitic and primary basaltic magma under varying tectonic conditions’.

On her life at this time, Joplin later commented: ‘I seemed to be stuck in rocks and thought it was about time I learned something about the humanities. While teaching during the day I studied for a Bachelor of Arts degree at night and did also a diploma of social studies.’ [8] Joplin received her B.A. and Diploma of Social Studies that same year from the University of Sydney.

Dr Germaine Joplin ‘in the field’ with her notebook and geology hammer.

Image courtesy the Joplin Family.

Juggling social work, teaching, and geological research in Sydney, Joplin decided to move to Canberra in 1951 to concentrate on geology with a job at the Bureau of Mineral Resources. The following year she accepted a permanent research post in the newly formed Geophysics Department at the Australian National University (ANU). Despite her great academic achievements, this was Joplin’s first permanent position.

Over the next 16 years at the ANU, Joplin supervised many PhD students, compiled chemical data on Australia rocks, became a Steward of University House, and wrote two important textbooks acclaimed for their contribution to the understanding of the chemistry and mineralogy of Australian igneous rocks (1964, twice reprinted) and metamorphic rocks (1968). Her indomitable spirit again prevailed when a fire in her laboratory in early July 1960 destroyed manuscripts, records, and a whole collection of rock specimens.

Joplin published numerous research papers and six books throughout her career. Her contribution to Earth Sciences was belatedly honoured in 1986 when she was awarded the prestigious W.R. Browne Medal for ‘distinguished contributions to the Geological Sciences of Australia’, as well as being made a Member of the General Division of the order of Australia (AM). She was never elected to the Australian Academy of Science, even though she was recommended several times. Joplin passed away on 18 July 1989.

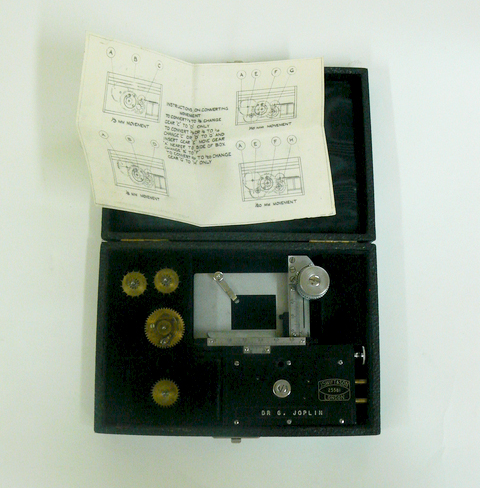

The National Museum holds a collection of laboratory equipment used in the study of geophysics by Dr Germaine Joplin, Professor John Jaeger and Professor Mervyn Paterson who worked at the Australian National University’s Department of Geophysics, in the then Research School of Physical Sciences, from the 1950s. Dr Germaine Joplin’s and Professor Mervyn Paterson’s research into rock physics during the 1960s underpins our contemporary understanding of the movement of continents. Joplin’s research used petrographic microscopes fitted with point-counting equipment for directly measuring the abundance of different minerals using rock thin sections.

This blog post was developed with contributions from Lisa Catt and Jennifer Moncrieff.

[1] Germaine Joplin quoted in The Canberra Times, 6 August 1968, p10

[2] Chris Brennan-Horley ‘The Biography of Germaine Anne Joplin’ (unpublished), f2a

[3] Chris Brennan-Horley ‘The Biography of Germaine Anne Joplin’ (unpublished), f4a

[4] Germaine Joplin’s citation for the W.R. Browne Medal of the Geological Society of Australia, Society News, 1986

[5] The West Australian, 17 March 1934, p8

[6] Germaine Joplin’s citation for the W.R. Browne Medal of the Geological Society of Australia, Society News, 1986

[7] Germaine Joplin’s citation for the W.R. Browne Medal of the Geological Society of Australia, Society News, 1986

[8] Germaine Joplin quoted in The Canberra Times, 6 August 1968, p10