A lyre by the fire

How did a firescreen made from the tail of one of Australia’s most iconic birds end up in a British home?

That’s the question student Leah Morberger explored as part of her work experience with the PATE team last week.

Leah was researching a firescreen that was recently acquired by the Museum. The brass screen features a lyrebird’s tail mounted on a satin backing and sandwiched between wood and glass. It has a label attached to the back, inscribed by Maud Thomas: ‘An Australian Lyre Joy bird’s tail modelled by my father, William Plowman, who was Managing Director of the taxidermist firm of Rowland Ward Ltd. He started work here in 1874 at the age of 14 and retired at the beginning of the First World War 1914 aged 54 and died in 1948 aged 87.’

Beginning with this label and some collection background prepared by the curatorial team, Leah has investigated the story of the screen. Here’s what she found out.

Taxidermy isn’t a prominent profession these days, primarily due to the animal protection laws and reserves present in the majority of countries. It is also a popular preference of our current population to see animals living in the wild, or in zoos, rather than as a stuffed ‘still life’. However, during the mid-Victorian and early Edwardian era taxidermy was a thriving industry with natural history objects, including bird feathers and hunting trophies, being used as popular décor.

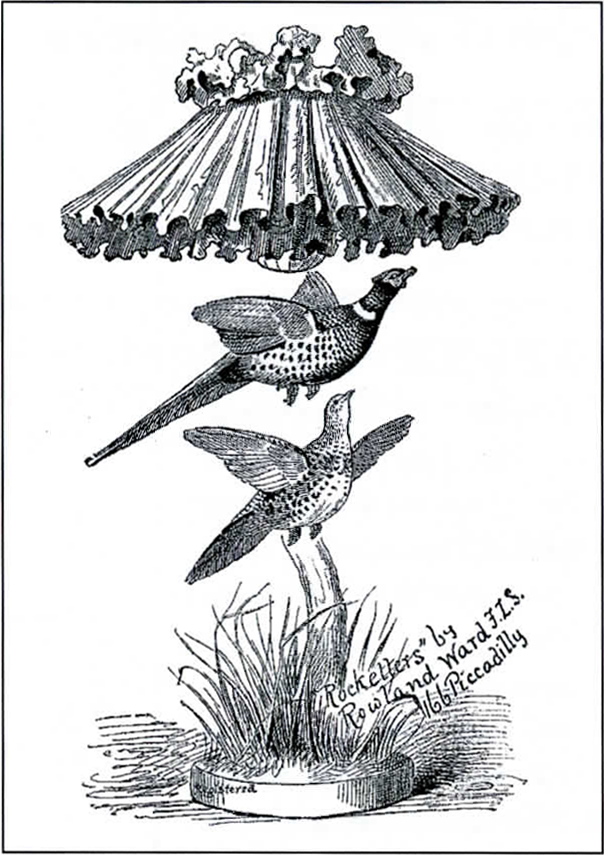

The lyrebird fire screen recently acquired by the Museum was created by William Plowman, a key taxidermist of the famous Rowland Ward Ltd. Company from 1874-1914. Throughout the 19th century, fire screens were used to protect the people sitting around the fireplace from the heat and sparks. They also served as a decorative feature to hide the opening of the fireplace when it was not lit.

The decoration of this screen features the feathers of a male lyrebird, a native Australian animal, found in the forests of South Eastern Australia. The fire screen is significant as it can help give us a sense of how elements from the natural world appeared in the Victorian home, and the popularity of both taxidermy and lyrebird tail feathers at the time.

The lyrebird is greatly admired for its spectacular feathers, which are commonly associated with the ancient Greek instrument of the lyre. However, the males of the superb lyrebird species are the only birds to exhibit these unique tails, as they use them to display territorial defence, and to attract female lyrebirds. Lyrebirds are also greatly admired for their ability to accurately mimic the sounds they hear, such as the call of a kookaburra or the grey shrike-thrush. In one of the early accounts of the lyrebird, the First Fleet’s Judge Advocate David Collins describes the lyrebird’s tail in incredible detail, and calls it as a ‘curious and handsome bird’. The distinctiveness of the lyrebird continued to catch the attention of many early settlers, with a newspaper in 1845 describing them as ‘the prettiest feathered songsters never before known” and a poem by Charles Harpur published in 1860, evoking their distinctive voice: “And the lyre-bird starts with clamors shrill”. The immense interest in the lyrebird continued throughout the years and contributed to the mass trade of their tail feathers, of which many were used for taxidermy items, including the firescreen.

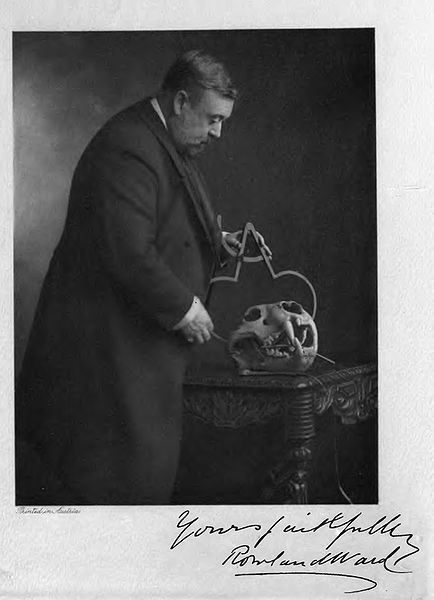

In Britain and Australia during the Victorian era, taxidermy was beginning to move away from purely scientific uses, and into home décor, particularly because of the fascination that many people had with the natural world. One of the most famous taxidermy companies of this era was Rowland Ward Ltd.

Rowland was born in 1848, the son of Henry Ward, an established taxidermist at the time. He left school and went to work in his father’s taxidermy business when he was only 14, and by 1873 he began operating his own taxidermist company. His ambitious display at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886, which contained around a hundred trophy animals from India, amazed the crowds and established his popularity throughout Britain. Later, in 1898, Rowland Ward re-established his company in Piccadilly, London, and could claim members of the royal family among his customers. His popularity and ambitious projects resulted in a constant stream of orders and his Piccadilly premises were nicknamed ‘The Jungle’. Many of his techniques are still used today.

Ward published many books about taxidermy and popularized the use of taxidermy items as furniture. However, we are still unsure how Ward’s company acquired the lyrebird feathers, with which William Plowman created the fire screen.

Lyrebird tails in Australia during the Victorian era were primarily collected to be used as ornaments and decorations. In George Bennet’s Wanderings of New South Wales, it is mentioned that in the early 1830s many men would hunt lyrebirds and sell their tails from 20 to 30 shillings a pair. Later, in the 1840s, George Augustus Robinson reported that lyrebirds were hunted by the Indigenous people of the Wurundjeri tribe, who sold the tails to Melbourne exporters in exchange for firearms. The tails were also exported in large amounts during the plume trade of the early 20th century, with reports that thousands of tails were sent overseas during this period. It is unclear whether Ward sourced the feathers from these exports, or if perhaps he sourced them from his aunt Jane Tost who was living in Australia at the time. Jane Tost and her daughter Ada Rohu were operating a taxidermy business in Sydney from 1872, and could have possibly supplied Ward with the feathers, or perhaps mentioned their distinctive beauty. Nevertheless, the trade of animal products between Australia and Britain most definitely occurred for this object to be made.

William Plowman’s fire screen helps us understand how the Victorians lived and the popularity of taxidermy in the 19th century domestic sphere. For many Victorians, the lyrebird’s tail would have brought a sense of natural beauty into their homes and a chance for them to encounter Australian wildlife. We may not yet know where the lyrebird whose feathers are featured made his home in Australia, but it is intriguing that his tail ended up in a screen shielding faces from the fire in chilly England.

Thanks to Leah for her contribution.

Do you know of other decorative uses of lyrebird feathers? Tell us about them in the comments.

Feature image: Superb Lyrebird dancing on courtship mound. Dandenong Ranges National Park. Photograph by Fir0002. From Wikimedia Commons.