The Path of the Bogong – Festivals of the Mountains

My name is Patrick Bailey. This is the second of three posts that I’ve prepared as an intern at the National Museum of Australia (and as part of the Australian National Internship Program), which explores how the interaction between human and non-human forces in the alpine region of Southern NSW and the ACT combine to form continual and changing expressions of community identity across time. This second post explores Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal practices which enabled strong connections between people and their environment.

Bogong Moths

“In summer the arrival of the Bogong moths provided another food source…[they] travelled to the Alps… not just about food, they involved ceremonies and exchanges between different groups. The opportunity to climb the mountains was an important spiritual experience.” (Matthew Higgins, Rugged beyond Imagination: Stories from an Australian Mountain Region p. 13).

One of the most significant events that transpired in Alpine Australia was the annual Bogong moth (Acrotis infusa) migration. The Bogong moth migrates in its millions annually from Southern Queensland through NSW, Canberra and eventually into Southern Victoria to escape the summer heat. It is not known how long this migration has taken place, but some estimates place this journey approximately 16,000 BP, or the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), following a rise in earth’s temperatures and a retreat of glaciers. The moths would aestivate (hibernate) during these warmer months between October to January. The Indigenous Bogong moth ceremony was held between October/November through to January/February the following year and represented the intimate relationship the Aboriginal tribes held within the land around them.

It is not known when Aboriginal groups started harvesting these nutritious insects, though evidence from Bogong Cave (excavated by Flood, 1974) suggests a minimum date of 1000 BP. The river pebble (now held by the NMA) uncovered by Flood in 1974 from Shelter II of the Bogong Caves and Shelters reveals how the Aboriginal people were using their toolset of stone implements in combination with moth hunting practices to create moth paste or cake. Robert Vyner, the only known eyewitness of this process recalls in 1865, how pebbles were used to grind the moths “into a paste by the use of a small stone and hollow piece of bark, and made into cakes”.

Alpine Skiing

The cultural meanings of skiing – whether communicating with or conquering the mountains (or both) – are similarly reliant on the landscape. These forms of dependence have inspired skiers and their representatives both to alter their perceptions of the Alps and to make material changes to the landscape itself.

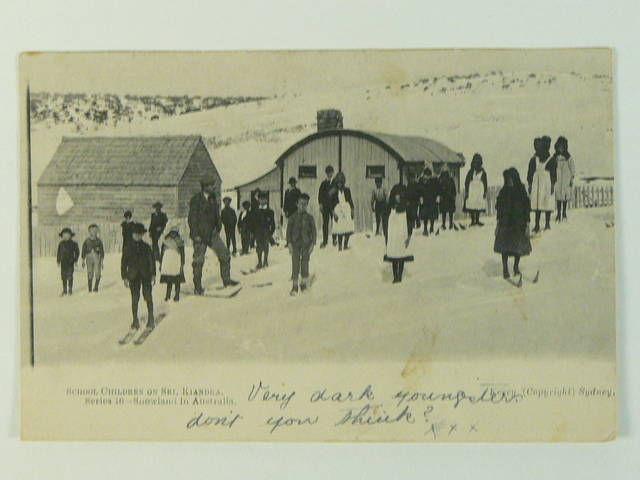

Now a ghost town, up until the 1970s the small alpine town and location of Kiandra was a place of gathering for both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. It was during winter however, that the land called to people and alpine skiing thus developed. Alpine skiing in Australia was first established by miners working at the Kiandra gold mines in the 1860s. Kiandra, along with a ski club in Norway, was the first ski club created in the world. The establishment of this club just 70 years after the first Europeans settled in Australia is a testament to the power of the land in drawing people into establishing connections, and a culture which persists in other areas around Australia today.

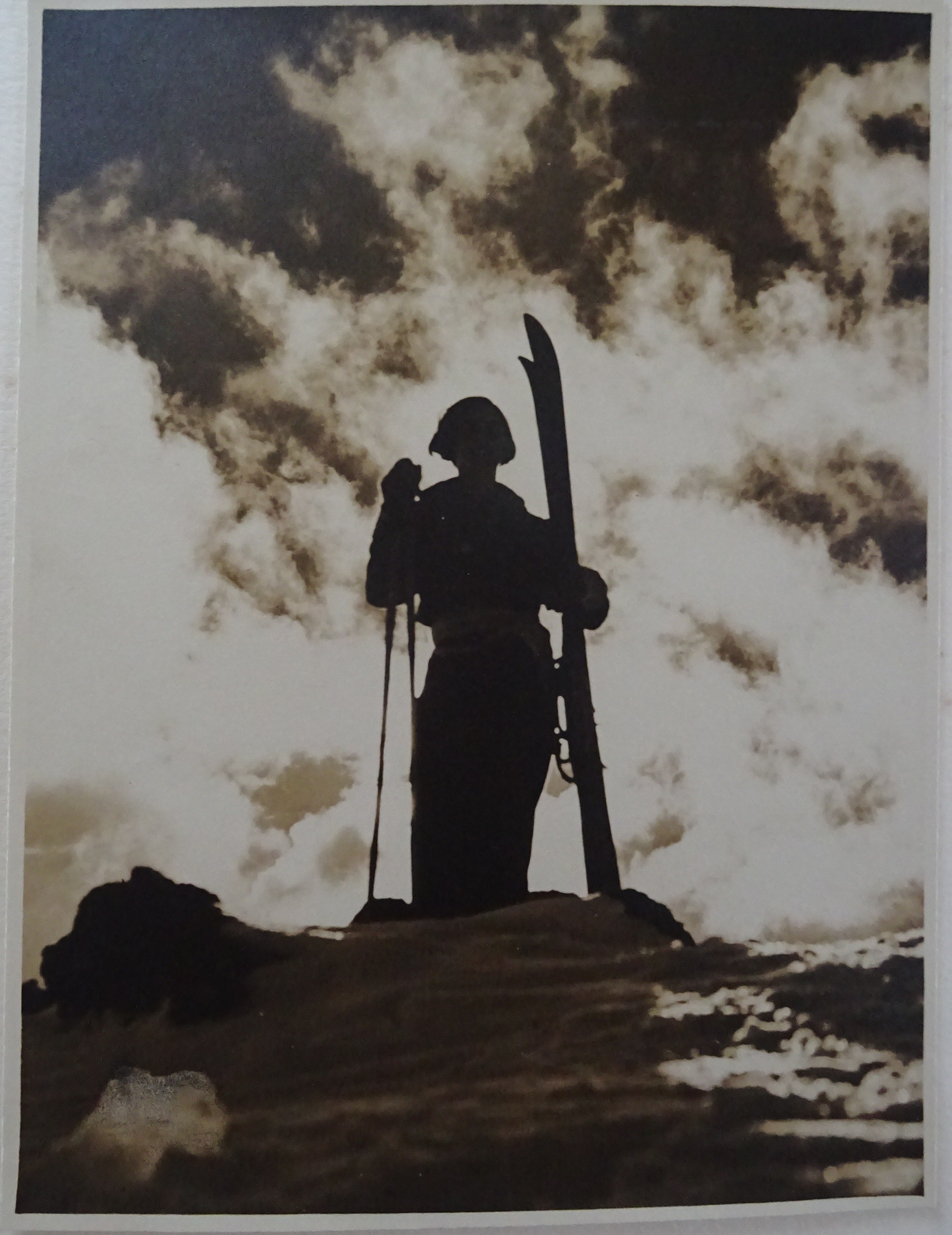

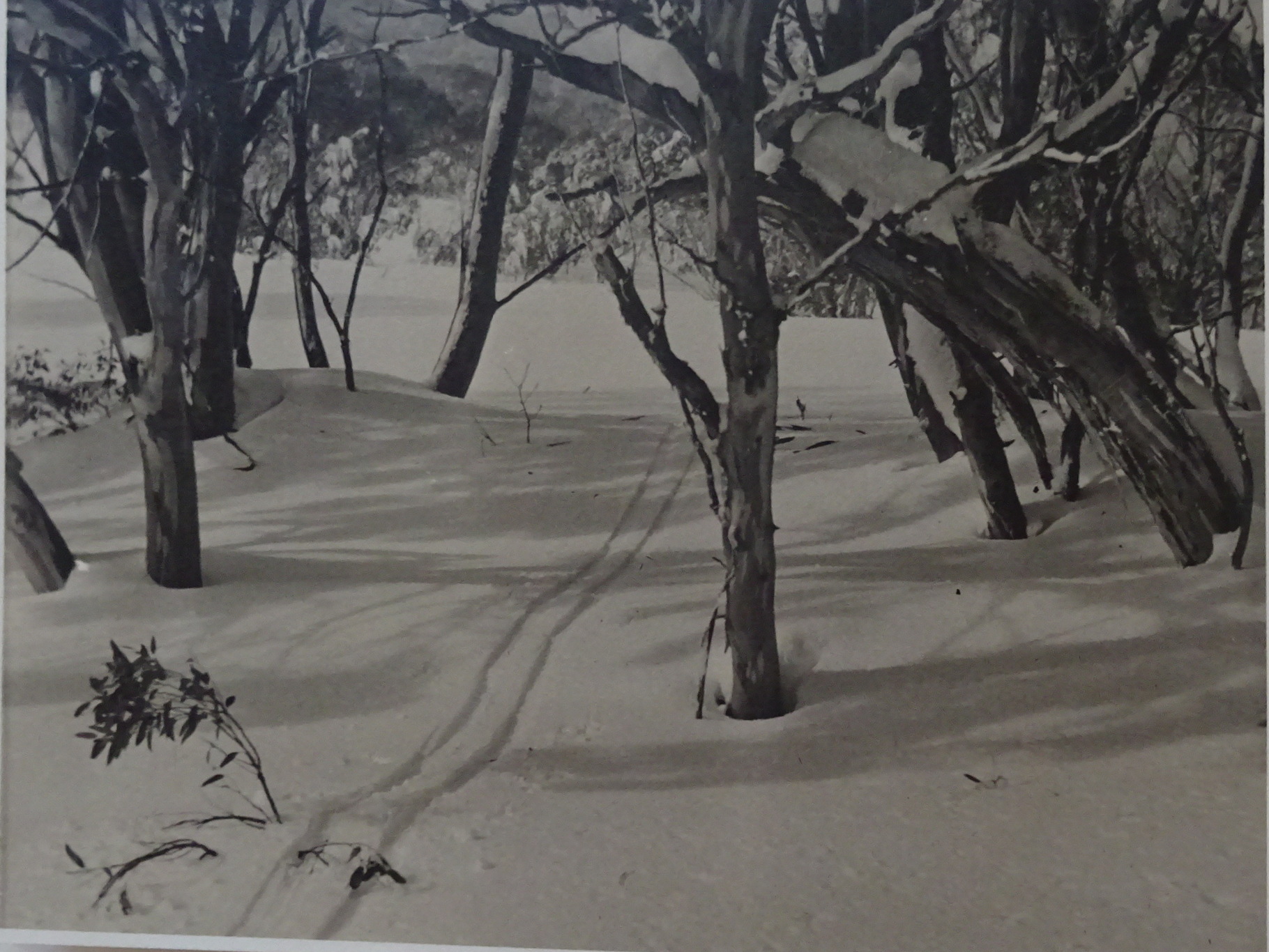

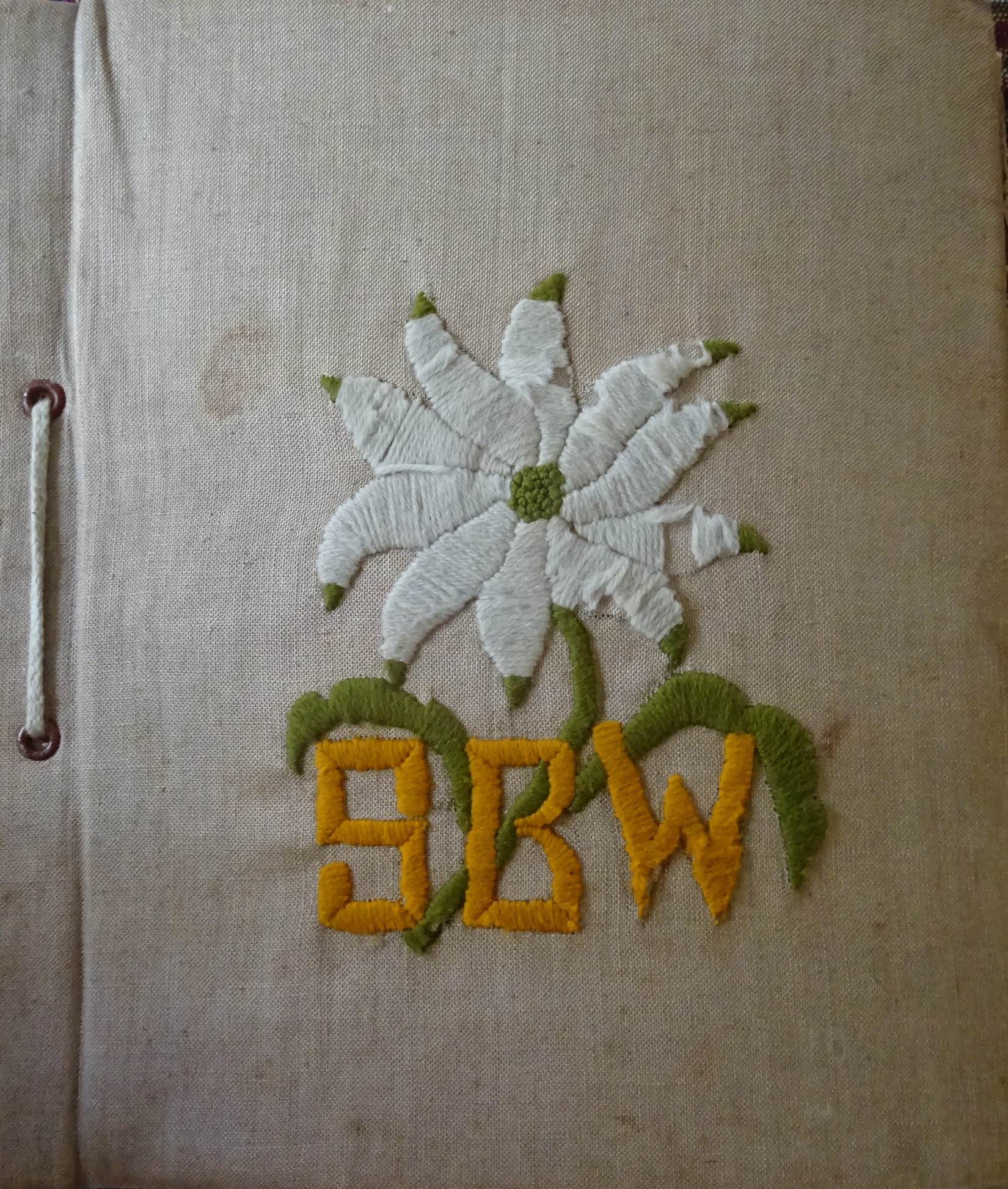

One group of people who certainly engaged with and gained an identity from the environment was Tom and Jean Moppett and Oliver Moriarty. These three adventurers travelled widely in Alpine Australia between the 1930s and 1960s. However, it was their trip from Kiandra to Kosciusko which captivates our attention. During a trip to Sydney in April this year to visit Nancy Pallin and her sister Kate (who unfortunately could not be there) about a new collection proposal, we viewed a number of significant artefacts. These artefacts included skiing equipment used by their parents Tom and Jean, and an extensive photo album. The NMA is acquiring this collection of artefacts that record and memorialize particular human experiences within the alpine environment. The collection is both extensive and captivating. The photo album captures the majestic beauty of this extraordinary landscape in vivid and captivating detail.

The attention to detail captured in the photos as well as the personal connection to their homemade alpine gear reveals the strong relationship that both Tom and Jean had to the region. The fact that Jean fashioned her own clothing is significant for two primary reasons. Firstly, they recognise the lack of availability of outdoor wear within Australia that was suited to the alpine region. This may also suggest that gear that was available was overly expensive for most people. Jean’s creations signify a strong desire to ski and she would do all she could to ski. On the other hand, the 1930s and to a lesser extent the 1940s were a period of economic turbulence across with world due to the Great Depression leaving many without a stable income. Thus, being able to ski demonstrates Jean and Tom’s strong desire to be a part of the land. Secondly, the clothing, particularly Jean’s hat, creates such a personal connection that she fashioned this item to memorize her experiences of skiing. The photos, aside from capturing the alpine landscape in sublime detail, represent the significance of the land to Tom, Jean and Oliver. Jean, Tom and Oliver are just a few people who have been draw into the Alpine region and become captivated by its chilly brilliance.

Bushwalking and National Parks

As with alpine skiing, bushwalking was concentrated around the concept of how personal connection to land shapes and defines identity. While not unique to Australia, it was in this land that physical, spiritual and emotional connections to land instigated the greater development of national parks and a fundamental desire to connect people to land. Bushwalking was the result of this desire, made possible through Australia’s ancient and diverse landscape.

One of the early clubs was Canberra Alpine Club (1930s) which was used as both a skiing club and bushwalking club. Members of this club enjoyed bushwalking but also became known for their intimate knowledge of the Canberra alpine region. In search and rescue missions it was often one of the Club’s members that led rescuers. Other clubs, such as Mountain Trail’s Club (1914) and Sydney Bush Walkers (1927) both expressed similar connections to the environment which bushwalking was able to provide.

Ultimately, these clubs motioned the development of national parks, through their long connection to and concern for the protection of the environment. As bushwalking is the desire to connect to the non-human elements of the world, those still untouched by human development, national parks were the logical product of this desire: the protection of land or ‘wilderness’ from human influence. Through bushwalking, national parks have expanded to reciprocate the emotional connection people in Australia have had and do have with the Australian landscape, and their desire to protect it.

For Myles Dunphy and his son Milo, bushwalking in nature was an experience which was fundamental to being human. The interaction between the non-human world and the human world was paramount in exploring humans relationship to the environment. Both men were proud advocates for the protection of land and through their bushwalking and conservation clubs, enacted a series of environmental protection reforms which have shaped the purpose of national parks and conservation areas in Australia today. These movements included the purchase of the lease for Blue Gum Forest (in the Blue Mountains), the formation of the National Parks and Primitive Areas Council and the development of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. The desire to protect the land, through the establishment of national parks, was engineered from the influence of the non-human environment, which captivated human wonder and sensual experiences.

Top image: Bogong performance at Tidbinbilla, 2006. Photograph by Pierre Pouliquin, courtesy Flickr Creative Commons.