The Path of the Bogong – The Landscape

My name is Patrick Bailey. As an intern at the National Museum of Australia (and as part of the Australian National Internship Program), it has been my privilege to research and compile a report on interactions between human and non-human forces in the alpine region of Southern NSW and the ACT, and how they combine to form continual and changing expressions of community identity across time. This research is designed to contribute in part to the development of one component of a new gallery of environmental history at the Museum. This research explores key alpine areas in order to communicate human/non-human relationships, the results of which will be discussed here.

This is the first of three posts which aims to explore how interactions between human and non-human forces in Southern NSW and the ACT combine to form continual and changing expressions of community identity across time. This first post will provide an understanding of the land, its environment and land use by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people.

The Alpine Landscape and Land Use

The Land

The high country or alpine region of Australia is one of the most significant bioregions in Australia. It encompasses an area of approximately 12,330 square kilometres or 1,232,981 hectares, with peaks of over 2000 metres above sea level. It is singular in Australia for providing the only region where year-round snow can occur. Over 21 species of alpine tree are native to the region, with over 30 species only found in alpine regions. The area is divided between four main regions encompassed under the broader term of Southern Uplands:

- The Southern Tablelands – Situated between the Blue Mountains and the Snowy Mountains and encompasses an area of approximately 13,000 square kilometres. It is general a low-lying area (550-750 metres) and is characteristic of open and treeless plains. Three prominent features include Lake George, Lake Bathurst and the Murrumbidgee River. The climate is considered to be continental insomuch as winters are cold (5-7.8°C) and summers are hot (20-21.7°C), with rainfall between 560-890 mm per year.

- Namadgi Ranges – This collective name (also known as the Australian Capital Territory Ranges) comprises the Tidbinbilla, Brindabella, Bimberi, Scabby and Booth Ranges. These ranges have a maximum elevation of 1830 metres and contains Bogong Mountain (1525 metres). The Murrumbidgee River also flows through these ranges on its way to intersecting with the Murray River in Victoria.

- Monaro – Situated south of the Namadgi Ranges this area comprises an area of approximately 15,500 square kilometres. This region is comprised of four distinct environments: alpine (1750-1830 metres tree line to an elevation of 2230 metres at Mount Kosciuszko), sub-alpine (1525-1830 metres), montane (915-1525 metres) and tableland (610-915 metres).

- Victorian Alps – Situated south of Mount Kosciuszko, this region has an average elevation of 1220 metres. It is characterised by open plains with forested regions and surrounded by steep slopes. It is generally covered in snow during the winter months (June, July & August).

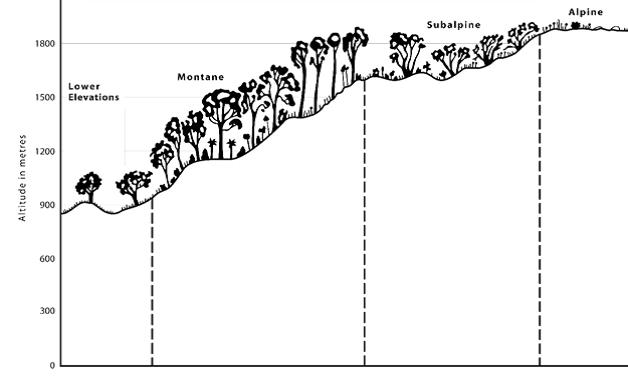

Figure 1: Australian Alpine bioregional zones, source: https://theaustralianalps.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/vegetation.pdf |

These regions fit into four categories:

- Alpine – areas above 1850 metres. This area is characterized by extensive open fields with scattered ground-hugging plants such as the snow daisy (Celmisia sp.), heathlands and feldmark (Erythranthera pumila).

- Subalpine – areas between 1400-1850 metres. This area is dominated by snow gum with an understorey of dense heathland and feld plants. However, large areas are also left open in the valley regions, which have become iconic of the region.

- Montane – areas between 1100-1400 metres. This area is characterized by dense coverage by stringybark and gum-type trees. Most common in this region are the peppermint forests (Eucalyptus radiata), blue gums (Eucalyptus globulus), mountain gums (Eucalyptus dalrympleana), candlebark (Eucalyptus Rubida), ribbon gum (Eucalyptus viminalis) and alpine ash (Eucalyptus delegatensis). However the most common tree is the snow gum (Eucalyptus pauciflora).

- Tablelands – areas below 1100 metres. This area is characterized by red gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis), yellow box (Eucalyptus melliodora), ribbon gum (Eucalyptus viminalis) and candlebark (Eucalyptus rubida). In high rainfall areas the alpine ash (Eucalyptus delegatensis), mountain gum (Eucalyptus dalrympleana) and mana gum (Eucalyptus viminalis) dominate.

Land Use

Alpine Australia has both shaped and been shaped by Indigenous and non-Indigenous people who have lived or encountered the region, creating a unique cultural landscape still existing in part today.

Indigenous Land Use

Alpine Australia is perhaps one of the most majestic places in Australia. It is home to over 21 species of alpine tree native only to Alpine Australia. It contains Australia’s tallest peaks, including Mount Kosciuszko and Mount Bogong. For over 21,000 years this region was home to many Aboriginal tribes including the Ngarigo, Omeo, Bidawal and Kranatungalung. These tribes would move within the landscape as the seasons changed. During summer the tribes would ascend to the peaks of the ranges for important ceremonies and to access wild game such as opossums, wombats and kangaroo. During winter the tribes would move closer to water sources in the lower ranges to escape the cold. Here they would fish and hunt the kangaroo on the vast grass plains and mid-range plateaus. From the 1830s, with the arrival of Europeans ‘squatters’ these native food and plant sources changed. This was the result of introduced species and disease pandemics among the tribes. The most virulent disease was smallpox which killed hundreds of Aboriginal people. These changes forced Aboriginal people to either adapt or move away from their traditional land. Such forced change resulted in new land practices, such as becoming a pastoral worker or a guide/scout.

Others were forced away from their land which resulted in increased interaction with other tribes and the inevitable debate over resources. Due to the strong seasonality of the region, resources were dependent on location and the time of the year from which they could be harvested. Due to limited resources during the seasons then, violence often ensued amongst the tribes as they competed over the resources. Whilst violence between the tribes was not uncommon before Europeans, some tribes having extended animosity or hatred of others, the increased contact between the tribes exacerbated this violence. However, not all change ended in violence between tribes and between Indigenous/non-indigenous people.

Indigenous people such as Dicky Cooper, known primarily by the attribution of Dicky Cooper’s Bogong, a peak in Kosciuszko National Park, developed new connections to land and generated a new identity. Cooper became known as a stockman of the region.[1] Other sources refer to him as a “Chief [who] brought his group to the same place year after year. This locality became known as Dicky Cooper’s Bogong.”[2] The ascription of this land to Cooper, and its cartographic interest by Europeans, may suggest that he still maintained his annual pilgrimage to the Bogong Mountains for the Bogong moth festival. Conversely, the site name may have followed on from pre-colonial interaction. Similarly, the figure of Jemmy, King of Bolara Maneroo, known through his inscribed gorget now held in the NMA, shows a changing sense of identity and connectivity to the new land. This identity was fashioned by European settlers, whom crafted the gorget in a military style. The iconography of the kangaroo and emu are definitions of the Australian identity being formed through interactions between the Europeans and Indigenous Australians. While little is known about Jemmy, his gorget suggests that he had significant contact with European settlers to be awarded this gorget. Whether he was a significant figure within his tribe or conducted some form of service to the settlers is not known. However, the military style of the gorget represents a European understanding of how Aboriginal tribes were formed and how they were led. It is clear that this gorget was meant to represent this man as some form of leader within the tribe, but also a figure of importance for the Europeans. The location of Maneroo is now known as Monaro.

Jemmy, King Bolara Maneroo, National Museum of Australia.

Jemmy, King Bolara Maneroo, National Museum of Australia.

European Land Use

Europeans first established a presence in the region in the 1820s which dramatically altered both the landscape but also the animals, plants and people of the environment. For Europeans, this new land enthralled them and captivated their senses and connection to land. New species of animal such as cattle, horses and rabbits were brought in, as well as new species of plants, including corn, wheat and barley. From the wonder of this snowy landscape emerged community identities such as expressed in Banjo Patterson’s The Man From Snowy River and the development of skiing and bush walking. Other identifiers of the region include the Snowy Hydro-Electric Scheme and wild brumbies, the latter being a physical memory of a time and settlers roamed the alpine ranges herding cattle and living within the land.

These traditional owners formed inextricably links with the land. These connections included significant spiritual ceremonies and practices. One such ceremony was the Bogong moth ceremony, held every year between October/November and January/February. Not only was celebration a great food source, but it was also an important relationship building ceremony. From Tumut in the north to Bega on the east coast and Gippsland in the south, the Aboriginal tribes would come together to celebrate this event. During this event many corroborees would be held which were specific to certain practices. One such corroboree was a coming of age ceremony for boys.

Top image: Bogong moth sculptures, Acton Peninsula, by Jim Williams and Matthew Harding, ACT Archives, Flickr creative commons