A passionate pursuit: The Lady Helen Blackburn collection

“Since the earliest times, man has collected shells for food, for adornment, for domestic utensils and for their beauty.” Lady Helen Blackburn (1918–2005).[1]

As part of the background work for the development of a new environmental history gallery, we’ve been searching the Museum’s holdings for collections that will help illustrate some of the themes we hope to explore. The Lady Helen Blackburn collection features more than five hundred seashells from Australian beaches, reefs and islands, making it a perfect fit for a gallery on environmental history. The significance of this collection, however, resides not just in its breadth and the beauty of the shells themselves, but in the stories it tells of how, where and by whom they were collected, and the insights it offers into a truly remarkable Australian woman: Lady Helen Blackburn.

Lady Helen Blackburn was born Bryony Helen Dutton in 1918, the third of four children to a pioneering pastoralist family. She grew up on the historic Anlaby Station near Kapunda (the oldest stud sheep station in South Australia) and formed a close relationship with her younger brother Geoffrey Dutton, who would become a celebrated poet, novelist and historian. Incessant teasing by other children about her first name, Bryony, led her to adopt her second name, Helen. To close friends and family, however, she was always Chibs, or Chibby, a name that, according to Geoffrey, “obscurely originated from my father’s first sight of her.”[2]

The family spent summers at Rocky Point, the beloved family holiday home on the north coast of Kangaroo Island, where Helen’s curiosity and love of nature led to a passion for shell collecting that would last a lifetime.

In 1942, in the midst of the Second World War, Helen married U.S serviceman Captain William Curkeet and moved to America. Although the marriage was short-lived, it was her time in America that sparked her other great passion – aviation. She learned how to fly by ferrying warplanes in Little Rock, Arkansas, and gained her commercial licence in 1945. She would later become one of Australia’ s most respected women aviators, winning numerous awards and serving as Federal Secretary of the Australian Women Pilots’ Association.

In 1951, Helen married lawyer Richard Blackburn (later Sir Richard). They lived in Adelaide and started a family. Rocky Point remained a focal holiday destination, and Helen’s passion for shell collecting continued to thrive. “Shell collecting has been my greatest joy in life”, she later wrote. “Just walking on a good beach, hoping to find beach specimens has made me as happy as hunting for live specimens.”[3]

In 1966, Richard was appointed resident judge of the Supreme Court of the Northern Territory, where he presided over the first Aboriginal land rights case heard in an Australian court: Milirrpum v Nabalco (1971). While he found against the Yolngu claimants, his ruling acknowledged for the first time in an Australian court the existence of “a subtle and elaborate system highly adapted to the country in which people led their lives, … a government of laws and not of men.”

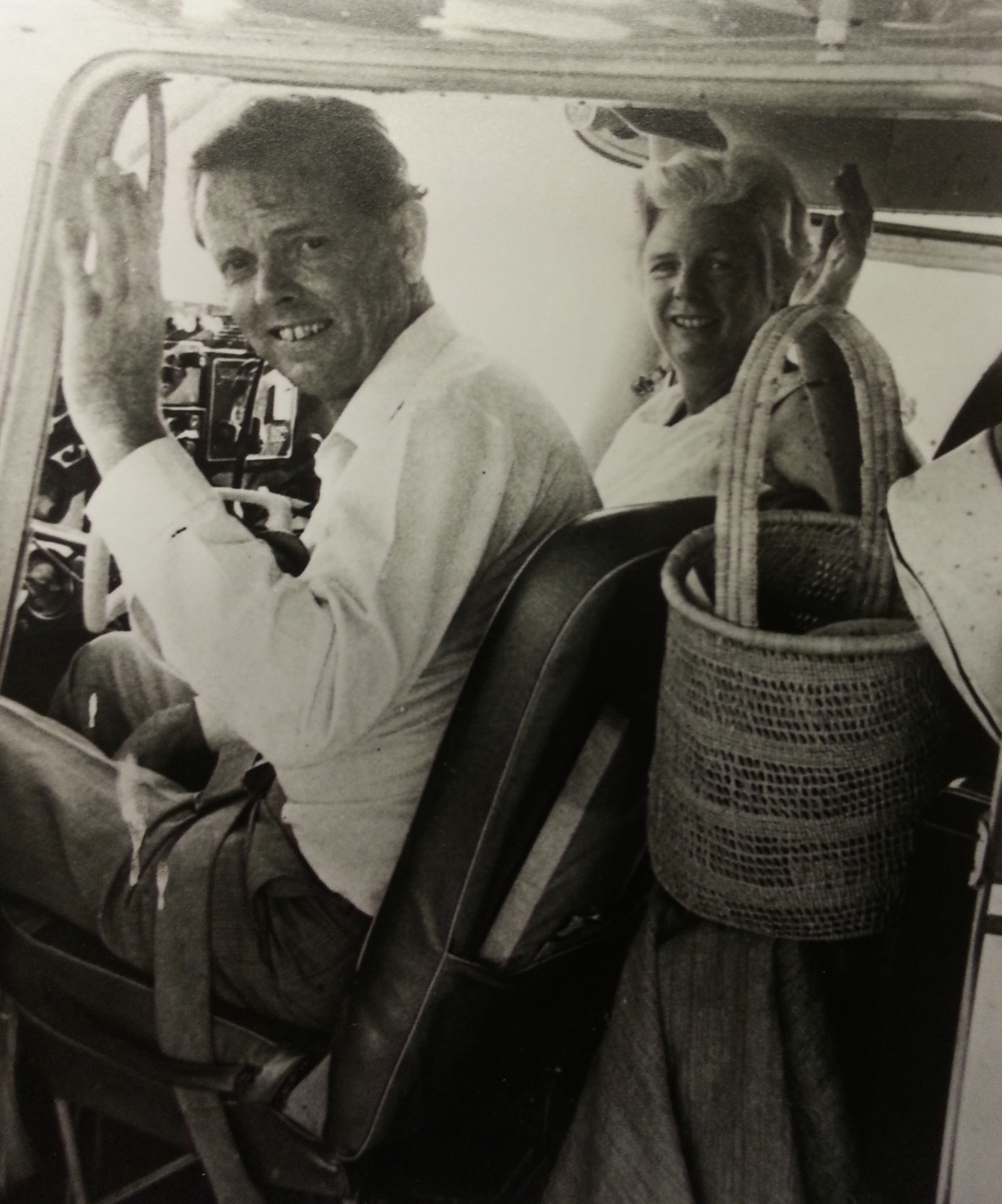

During her time in the Northern Territory, Helen pursued her passion for collecting shells. She visited the Gove Peninsula of Arnhem Land (the country of the Yolngu people of Yirrkala) with her husband, and took the opportunity to search for shells. She also used her pilot’s licence and Cessna to visit other remote regions. “The Cessna continues to give us our most enjoyable times up here”, she wrote in a letter to friends in 1968. “She is a real magic carpet in the Territory, where distances are so great and many places can only be reached by sea or air anyway.”[4]

On one trip she visited a beach near Port Keats Mission, where, when “searching along the water’s edge one night, I suddenly saw a crocodile’s snout sticking out of a wave – very close. I swung my torch squarely into his ruby eyes and he vanished in an instant. So did I!”[4]

Such was her skill and reputation for shell collecting, that she did so on behalf of several major institutions, including the Australian, Darwin, Tasmanian and Western Australian Museums, the CSIRO and the University of New South Wales. Her malacological knowledge, moreover, was such that she wrote a book on the, “Marine shells of the Darwin area”. One of the shells she presented to the Australian Museum had never before been described, and now carries her name: Cryptomya blackburnae.

Helen corresponded regularly with other shell collectors around the world, exchanging information and swapping shells to build up her collection. There are shells in her collection, for example, gathered by Rodney Fox who famously survived a great white shark attack, later overcoming his fear and becoming a professional abalone diver and passionate advocate for shark conservation.

The collection also includes a specimen of the world’s largest known gastropod, the Australian trumpet Syrinx aruanus (which regularly exceeds 70cm), collected by ranger David Lindner. Another large shell in the collection is the horned helmet Cassis cornuta collected by pearl divers working for Michael Paspaley, the master pearler of Darwin. “Mr Paspaley normally did not let his divers collect other shells,” wrote Helen, however “as a present to me, he instructed them to collect two C. cornuta.”

In 1971, the Blackburns moved to Canberra, where Richard took up a position with the ACT Supreme Court. This allowed Helen to broaden her collection to include shells from the New South Wales south coast, where Canberrans regularly holiday. In fact, Lady Helen’s notes regarding when and where shells were discovered provide a fascinating record of her many travels over the years. She was, of course, a regular visitor to Kangaroo Island, collecting shells there from 1955 until the 1980s. She also regularly visited Queensland’s Great Barrier Reef, and the Kimberley in northwest Australia, especially during her Darwin years in the late 1960s. In 1964, Helen flew her brother Geoffrey across the Nullarbor as research for his biography on Edward John Eyre: The Hero as Murderer.

With such a close association with beaches and coastlines around Australia, Lady Helen saw firsthand the threat of pollution on the environment. In 1971, she told the Canberra Times:

“I believe pollution is a threat, all right – even on Cape Wessel there is evidence of it. Right along the eastern side of the island there are great globs of oil – horrid thick heaps of it, rubbish from ships, pieces of torn plastic and all sorts of refuse … no, I don’t think scientists who issue warnings are alarmists.” [5]

In 1984, Lady Helen offered her seashell collection to the National Museum of Australia. Director Don McMichael – a marine biologist who studied Australian freshwater shells for his PhD thesis – gratefully accepted, replying:

“The Museum is very grateful to you for offering us this collection – the first substantial natural history material that we will have acquired. I can assure you that, even though we may not ever get involved in taxonomic research on molluscs, we will make very good use of it over the years.”[3]

It may have taken a few more years than he expected, but with the development of a new gallery on the environmental history of Australia, we expect to make very good use of this significant collection, and by doing so pay respect to a very remarkable Australian woman.

Acknowledgements

Images of Helen and Richard Blackburn courtesy of Charlotte Calder and Tom Blackburn.

References

[1] Helen Blackburn, Marine shells of the Darwin area. Museums and Art Galleries Board of the Northern Territory: Darwin, 1974.

[2] Geoffrey Dutton, Out in the open: an autobiography. University of Queensland Press: St. Lucia, Qld, 1994.

[3] Lady Helen Blackburn collection file: National Museum of Australia.

[4] Papers of Lady Helen Blackburn, 1944-1990 [manuscript]. National Library of Australia.

[5] Barbara Hines, An airborne collector of shells comes to town. Canberra Times: 13 August 1971.

Feature image: Three Charonia rubicunda shells from the Lady Helen Blackburn collection. Photo: Stephen Munro