Battles with Morpheus: Hubert Opperman and the 1931 Paris-Brest-Paris

In early September 1931, the cyclist Hubert Opperman developed a sore throat. This somewhat unremarkable fact might have otherwise passed unnoticed among the array of domestic and international issues that demanded the attention of Australian journalists. And yet, newspapers from the Melbourne Age to the Murrumbidgee Irrigator all commented earnestly the on the state of Opperman’s upper respiratory tract as he prepared for yet another gruelling endurance contest on the other side of world that most Australians had never heard of. The event in question was a non-stop race covering 1,200 kilometres from Paris to the west coast town of Brest and back again. It was then the longest race in the world and the winner was expected to complete the journey, without sleep, in a little over 50 hours.

At midday on 3 September, around 30 of the best riders in the world set off from Paris and headed west. Through the first day and night, they encountered gales and heavy rain. After 24 hour of continuous riding, the depleted peloton reached the turnaround point of Brest. Some had already abandoned, unable to carry on without sleep. Much worse was to come. As darkness fell on the second night, fatigue slowly washed over the remaining men. One by one, Morpheus, the Greek God of Dreams, dropped his hammer upon the riders. The men drifted in and out of consciousness. Some wobbled. Some crashed. Lights from the team cars cast curious shadows that danced and transformed into spectators and animals who rushed onto the road, only to disappear moments before a collision. As Opperman later recalled:

‘I was wretched with fatigue….For hours I fought against the insidious onset of sleep. I whistled. I shouted; I strove to think of anything so that Morpheus would not clutch me too fiercely…it was agony.’

Morning finally came. Five men had managed to shake the ‘demons of sleep’ for a second night. Opperman was among them and looked to break away. His first attack was immediately shutdown by his rivals. His second also failed. Then, on a low hill, Opperman launched his most ferocious attack, throwing everything he had into the pedals and taking advantage of his light, climber’s physique. At last, he had shaken them. He now faced a 56 km solo pursuit to the finish. Opperman built a three-minute lead. But behind him came the pack, which had grown to include the Belgians Leon Loyet and Maurice De Waele, France’s Marcel Bidot, Luxembourg’s Nicholas Frantz, and the Italian Guiseppe Pancera. The five riders, each champions in their own right, combined forces to erode Opperman’s lead. Oppy’s lead soon dropped to 2 minutes. His manager, Bruce Small, screamed from the car: “Oppy, ride like the devil!” Over the next hour, the group reduced to four men, but Opperman’s lead had crumbled to just 30 seconds with nineteen kilometres to go. At the five-kilometre mark, Opperman heard the sound of shifting gears. He had been caught. But what price had been the chase? Opperman launched another attack, but the four pursuers clung on like leeches. Opperman rolled to the back of the bunch as they approached the Velodrome Buffalo, rode over a stretch of cobblestones and down a muddy ramp and through a tunnel that lead to the concrete track of the arena. The lap bell sounded. Decroix was the first to move. He led out, followed by Loyet. Bidot then made a move but was unable to sustain the effort as Pancera took the lead. Opperman followed. Two hundred meters from the line, Opperman unwound his sprint, flying from Pancera’s wheel with enough momentum to win by two lengths. Forty thousand spectators suddenly transformed into a ‘mob of yelling lunatics.’

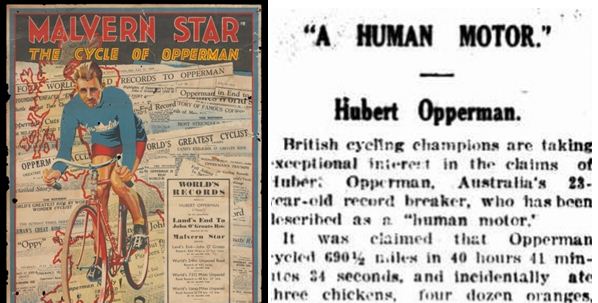

Opperman was the first non-European to win the Paris-Brest-Paris race and set a course record in the process. While he had acquitted himself well in the Tour de France, which was run two months earlier, it was this victory that saw him admitted to the pantheon of cycling gods. The French sporting press – never prone to understatement – lauded Opperman as one of the greatest cyclists of all time; a superman, a human motor, a flying machine. Australia followed suit and delighted in the fact that Opperman had upheld the nation’s prestige. And his career was far from over.

After success in Europe, Opperman spent the next decade setting a slew of transcontinental and intercity cycling records in Australia, cementing his status as a cycling and sporting icon. Gripping tales of Oppy’s cycling feats were rarely out of the press. He was a household name and as popular as Don Bradman and Phar Lap.

In a nation that stresses the experience of sport as important in determining who they think they are, most Australians do not remember the man more commonly known as ‘Oppy’, one of Australia’s greatest athletes. His life has not been subject to the scrutiny it deserves. Over the last few years, I have been interested to explore more precisely how Opperman attained his celebrity status and why his feats of endurance resonated powerfully with the Australian public. Contrary to the dominant line in Australian sport history, I think it is too simplistic to say that Opperman (as well as other sporting champions of the 1930s such as Don Bradman, Andrew “Boy” Charlton and Phar Lap) became popular because he was an entertaining distraction in the economic turmoil of the Depression. Opperman’s significance, I think, can be explained within the context of deeper cultural concerns about modernity, the capacity of Australia to recover from the First World War, industrial efficiency and race patriotism. The 1920s and 30s were characterised by a pervasive insecurity about the physical and moral condition of the nation. In this climate, Opperman fostered new understandings of athleticism, masculinity and the capacity of white Australians to thrive in a vast and sparsely populated continent.

The latest issue of Australian Historical Studies includes my article ‘The Human Motor: Hubert Opperman and Interwar endurance cycling in Australia’. It considers why Oppy became a national hero and how his spectacular cycling feats transformed popular understandings of human endurance and of the Australian continent itself. I have a limited number of electronic copies to give away, please send me an email and I will provide a link. daniel.oakman@nma.gov.au

Some Australians who might remember Oppy were in France last weekend, riding the Paris-Brest-Paris 1200 for themselves. The event has not been run as a race since the 1950s, when it began welcoming amateur cyclists who endeavour to complete the journey within 90 hours. It is held every four years and attracts thousands of riders from around the world.

Fun fact: The opiate morphine takes its name from Morpheus, the Greek God of Dreams.

What an amazing man and what a story. I am delighted the NMA is focusing on this man.

Thanks Winifred! We reckon he was pretty amazing as well. The National Museum has some great objects from Oppy, including his beret he wore for most of his life as a tribute to the reception he received in France. We don’t have his bicycle unfortunately! More on Oppy here. http://www.nma.gov.au/collections/highlights/hubert_oppermans_beret