World Mosquito Day: microscopes and wedding dresses

World Mosquito Day commemorates the discovery that female Anopheles mosquitoes transmit malaria between humans, made by British medical researcher Sir Ronald Ross on 20 August 1897. Since that day, researchers across the world have sought to understand mosquitoes and their role as vectors, developing methods to prevent and control the spread of disease. The material culture created in response to the mosquito reflects the wide ranging interests of scientific endeavour, environmental adaptations and social paradigms in Australia and across the world.

Research

As Sir Ronald Ross recorded the discovery in his diary, he noted the significance of the occasion, “the anniversary of which I always call Mosquito Day”:

“After a hurried breakfast at the Mess I returned to dissect the cadaver (Mosquito 36) but found nothing new in it… At about 1pm I determined to sacrifice the seventh Anopheles (A. stephensi) of the batch fed on the 16th, Mosquito 38, although my eyesight was already fatigued. Only one more of the batch remained. The dissection was excellent and I went carefully through the tissues… I saw a clear and almost perfectly circular outline before me of about 12 microns in diameter. The outline was much too sharp, the cell too small to be an ordinary stomach-cell of a mosquito. I looked a little further. Here was another, and another exactly similar cell.”

A Leitz dissecting microscope in the National Museum’s collection was used by entomologist Frank H Taylor to analyse mosquito specimens at the Australian Institute of Tropical Medicine (AITM) between 1911 and 1918. The AITM was Australia’s first medical research institute, situated in Townsville, Queensland, from 1910 to 1930. The National Museum holds over 30 items of laboratory equipment used by the AITM in Townsville as part of the School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine collection, many on display in the Landmarks gallery.

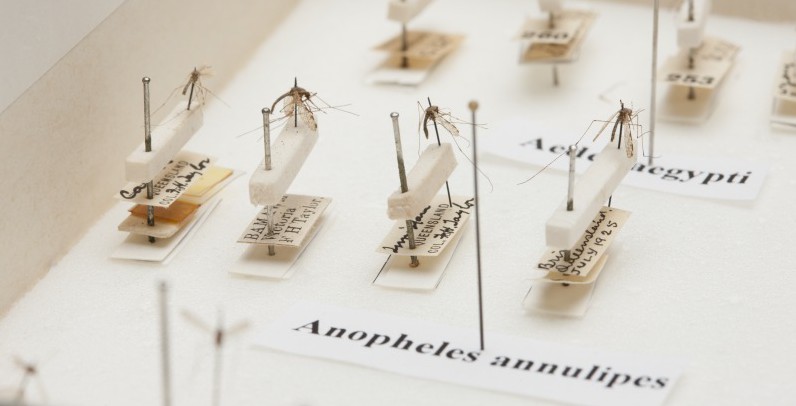

As it had been for Sir Ronald Ross, dissection was an important component of mosquito research at the AITM, establishing the taxonomy of mosquitoes and their vector status in relation to diseases. Taylor collected a large number of mosquitoes throughout Australia for a variety of analytical purposes, stating that: “The chief object of dissection is to determine what species of Anopheles are carrying malaria in nature under the particular local conditions.” The collected mosquitoes were killed one at a time for analysis.

When examining a mosquito for possible malarial infection, Taylor explained the dissection technique: “The specimens which show no sign of blood in their abdomen may be dissected, but those with blood in the abdomen must be held until after they have digested their meal, if possible until after the tenth day of feeding, to give the cysts an opportunity to develop on the stomach wall… When dead, the specimen is placed on its back on a slide. Then cut off with the scissors the legs and wings; catch hold of the specimen with the forceps by the proboscis and place on its back in a drop a saline on a fresh slide.” [1] Using the dissecting microscope, the head, thorax and abdomen of each mosquito was separated on a glass slide. Each body segment was then teased apart and examined.

Application

The AITM recruited Dr Anton Breinl and John Fielding from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, as the government sought to address concerns about the impact of the tropical climate and diseases on the productivity of the region’s population. After their arrival in Townsville in January 1910, they immediately began health surveys in north Queensland, the Northern Territory, the Torres Strait and Papua New Guinea, with entomologist Frank Taylor, biochemist Dr W J Young, bacteriologist Dr H Priestley and parasitologist Dr W Nicoll.

In 1920, Breinl presented his findings based on their first decade of wide-ranging investigations. Identifing few diseases of concern in northern Australia, the Institute concluded that health in tropical Australia depended on how people lived: their access to clean water, houses with good shade and air circulation, effective waste disposal, loose clothing, a healthy diet, low alcohol consumption and protection from disease-bearing insects.

The reason for investigating disease in tropical regions is the environment, where hot and humid climates present ideal breeding ground for mosquitoes. Areas of Queensland, northern New South Wales, the Northern Territory and Western Australia are considered tropical or sub-tropical, making them the most common sites of parasitic and insect-borne diseases in Australia. The prevalence of certain breeds of mosquitoes in tropical locations means that residents there are more exposed to the diseases carried and transmitted by those insects. For the control of mosquitoes, the AITM recommended spray-killing of adult mosquitoes, identifying and removing sources of water where mosquitoes could breed around homes and businesses, wearing protective clothing and repellents, installing gauze on windows and using mosquito nets over beds to reduce exposure to mosquito ‘bites’.

Upcycling

It is likely that mosquito nets have been in use for centuries, with some reference to Cleopatra sleeping under a mosquito net while Pharaoh of Egypt, and less famous examples recorded in texts from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. While scientists continue to develop vaccines, chemical and clinical interventions, international health organisations continue to promote mosquito nets as one of the best forms of protection against the spread of disease.

Within the National Museum’s collection is an example of how the ubiquitous mosquito net can also save a wedding day. When faced with restrictive Second World War rationing conditions during 1943, Ella Frances Lindwall sought out a creative solution to her problem of finding enough quality material to make a wedding dress. Ella’s answer was to have her dress made from recycled mosquito netting and parachute silk, and embellished with rows of curtain lace. The elegant dress was in turn borrowed and worn by two other women, Joan Jenkins (nee Booty) and Irene Christopher (nee Childs), for their weddings.

Ella’s upcycling effort predated more recent examples of mosquito net clothing worn by celebrities, such as Kate Moss, to raise public donations for malaria awareness campaigns.

The future

Despite extensive research, treatment and prevention programs, malaria remains one of the most widespread and deadly of all human parasitic diseases. The disease results from infection with one of five protozoan blood parasites, transmitted by mosquitoes of the Anopheles genus. AITM entomologist Frank Taylor wrote that “It is a well-established fact that the mosquito is the worst enemy of man.” [2] According to recent research, malaria parasites are thought to have killed half the number of people that have ever lived. [3]

The Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine (AITHM) is a newly-established tropical health and medical research institute as part of James Cook University, based in Townsville, Cairns, the Torres Strait and Mackay. AITHM researchers are part of the global efforts to eradicate malaria.

This year, more than 100 years after Sir Ronald Ross’s discovery, the European Medicines Agency approved the world’s first malaria vaccine for use, giving it the go-ahead to be assessed by the World Health Organisation. Perhaps its success will bring cause for the creation and celebration of a new World Mosquito Day.

[1] F.H. Taylor, Mosquito intermediary hosts of disease in Australia and New Guinea, Service Publication (School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine), Number 4 (Commonwealth of Australia, Department of Health, 1943), p 113.

[2] F.H. Taylor, ‘Mosquitoes’, The Australian Museum Magazine, September-November, 1942, p 57.

[3] http://www.malarianomore.org.uk/why-malaria

Feature image: Anopheles annulipes (mosquito) specimens collected by entomologist Frank Taylor during his employment with the institute, on loan from the National Insect Collection, CSIRO. Found throughout Australia, Anopheles annulipes is a known vector of malaria, and has also been shown to carry human filaria, dog heartworm, and Ross River virus. Photo Damian McDonald, National Museum of Australia.