Ulm’s trans-Pacific airline

In July 1934, Charles Ulm piloted his eighth crossing of the Tasman Sea from New Zealand to Australia, and then delivered the first official airmail between Australia and Papua New Guinea. Firm in his resolution to establish regular air services between Australia, New Zealand and north America, Ulm then began planning his second flight across the Pacific Ocean – this time, with the aim of having the effort recognised as a commercial enterprise rather than an act of daring.

Great Pacific Airways

During 1933, most of Ulm’s efforts had been targeted at securing the tender for the Australia-Singapore link of the Australia-England airmail service. In April 1934, the Commonwealth government announced that the contract had been awarded to the partnership of Qantas and Imperial Airways. Ulm offset his disappointment with further flights to New Zealand and then Papua New Guinea, quickly shifting his focus to establishing a trans-Pacific commercial air service between Australia, Canada, the United States of America and New Zealand.

In September 1934, Ulm registered a new company, Great Pacific Airways Ltd, with Sir Ernest Thomas Fisk as chairman and nominal capital of £500,000. The first tasks of the new company were obtaining a suitable aircraft and preparing airstrips across the route.

It was decided to make a demonstration flight to launch and promote the new company. Charles and Jo Ulm mortgaged their assets to finance the flight, and Ulm was able to secure a government guarantee of £8000 for the undertaking.

Ulm asked the experienced George Littlejohn, then chief instructor at the New South Wales Aero Club, to join him as co-pilot, and John Leon Skilling as navigator-radio operator.

Stella Australis

Ulm was determined to carry out the flight with an ‘all-British’ aircraft and crew. He decided on a twin-engine Envoy aircraft manufactured by Airspeed Ltd, with the addition of long-range fuel tanks, new Armstrong Siddeley Lynx 1Vc engines and the latest navigation instruments and wireless equipment. It was named ‘Stella Australis’, inspired by stars and patriotism as the ‘Southern Cross’ had been six years earlier.

Ulm and Littlejohn travelled to England by ship to oversee the final preparations of ‘Stella Australis’ and take receipt of the aircraft, while Skilling remained in Australia to undertake further training in radio operation and morse code before joining his colleagues in Vancouver.

‘Stella Australis’ was tested extensively in England and then loaded on to the Cunard ocean liner RMS ‘Ascania’ for transport to Canada.

While travelling, Ulm took the opportunity to write a draft autobiography, reflecting on his experiences and outlining his future plans.

Aviation is a public matter. Until the man and woman in the street can be persuaded to take a really intelligent interest in its development, no permanent progress can be made. Aviation is still in the stage where it needs and wants the support of Government and public bodies. That support cannot be expected or gained until public opinion is such that those in power can act in the full knowledge of whole-hearted support from those they represent. Much of my work in the past has actually been devoted to that end. Call it propaganda if you will, I see no shame in that term.

In the course of the activities I refer to, I have had to earn my living, but in so doing I have at least contributed in some measure to the fostering of true airmindedness amongst people who matter more to me than any others in the world.

As far as the future goes, my plans have now been made public. My sole object in making an all British flight from Canada or the United States to Australia is to pioneer the route for an All Red Airline between my own country and America and Canada.

The trans-Pacific flight made by Smithy and myself in 1928 certainly stimulated the public mind to a realisation of the safety and value of aviation as a method of transportation. I can see now, however, that that flight was given too much sensational publicity. The impression created was that we were two men who had achieved the ‘impossible’, and as time went on people said that nobody was likely to do the job again. This was patently absurd.

There is no more reason why there should not be regular trans-Pacific air services than there is that aircraft should fly regularly as they do between, say, London and India. My forthcoming flight will, I hope, eradicate the impression that trans-Pacific flying is extraordinary.

Long distance flying is no longer a hazardous undertaking reserved to pioneers, super-men, and daredevils. I believe the trans-Pacific air service to be a practical possibility. I believe that such a service can be operated under the British flag with British aircraft and British personnel. I do not minimise the hazards of the undertaking. All I can do is to reduce them to a minimum.

I believe I shall succeed, but whether I succeed or fail something will have been added to our knowledge of air transport, and nothing that I may do will be wasted if it advances the cause to which I have given the greater part of my life.

‘Come and pick us up’

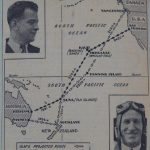

Ulm, Littlejohn and Skilling made further test flights in Canada, and then flew from Vancouver to San Francisco in late November. There, Ulm was able to meet with his friends Charles Kingsford Smith and Patrick Gordon ‘Bill’ Taylor, who had just completed a successful flight across the Pacific Ocean, from Sydney to Oakland in ‘Lady Southern Cross’.

After waiting several days for a favourable weather forecast, Ulm, Littlejohn and Skilling took off from Oakland in ‘Stella Australis’ on Monday 3 December, planning to fly from Honolulu to Fanning Island, Suva, Auckland, Sydney and Melbourne.

Progress was again charted by radio contact with land stations and ships at sea. It was only at after 6:00 am the next morning that the first signs of trouble for ‘Stella Australis’ were recorded. After repeated calls from the crew of ‘Stella Australis’ for the radio beacon signal, it became apparent that either their receiving set was out of order or they had flown off course.

Several hours later, with their fuel supplies exhausted and still unable to locate land, transmissions received from ‘Stella Australis’ reported that they had landed on the water, with the last messages reading “Can float for a couple of days” and “Come and pick us up”.

The US Navy sent aircraft, submarines and ships to search an extensive area during the following week, but no trace of ‘Stella Australis’ was found. The wives of Ulm, Littlejohn and Skilling rallied together for support, and after the official search was ended, Jo Ulm decided to charter a vessel to continue searching for another month as she continued to hope that the men had made it to one of the islands in the area. That search too failed to find any trace of the aircraft or crew.

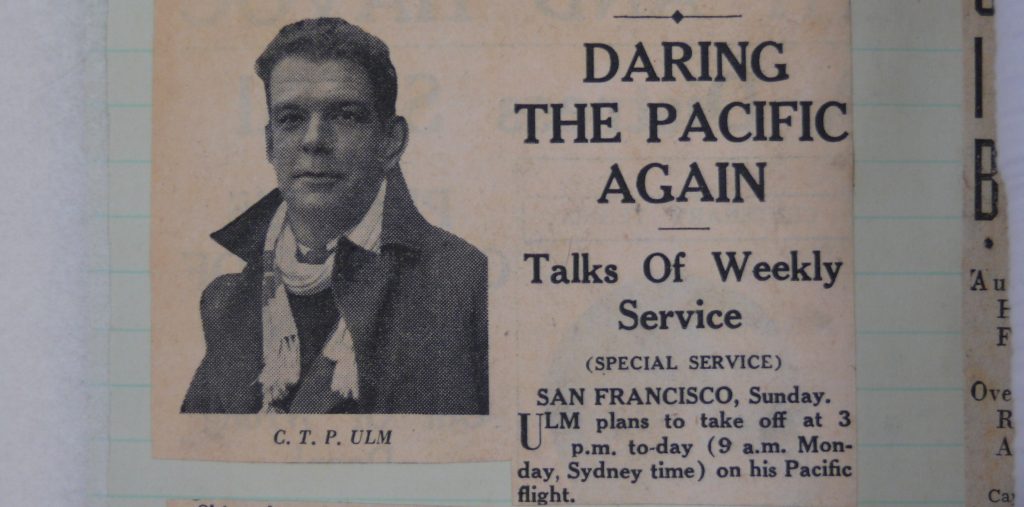

A scrapbook of newspaper clippings in the National Museum’s collection was compiled by Jo Ulm, following her husband’s work and then the search for the ‘Stella Australis’ and crew.

Ulm’s legacy – airlines across the Pacific Ocean

Years later, it was revealed that Ulm had been recommended for a knighthood on the completion of the trans-Pacific flight in ‘Stella Australis’. Many would wonder why Ulm had not received that recognition years earlier, with his achievements considered equal to those of his decorated contemporaries.

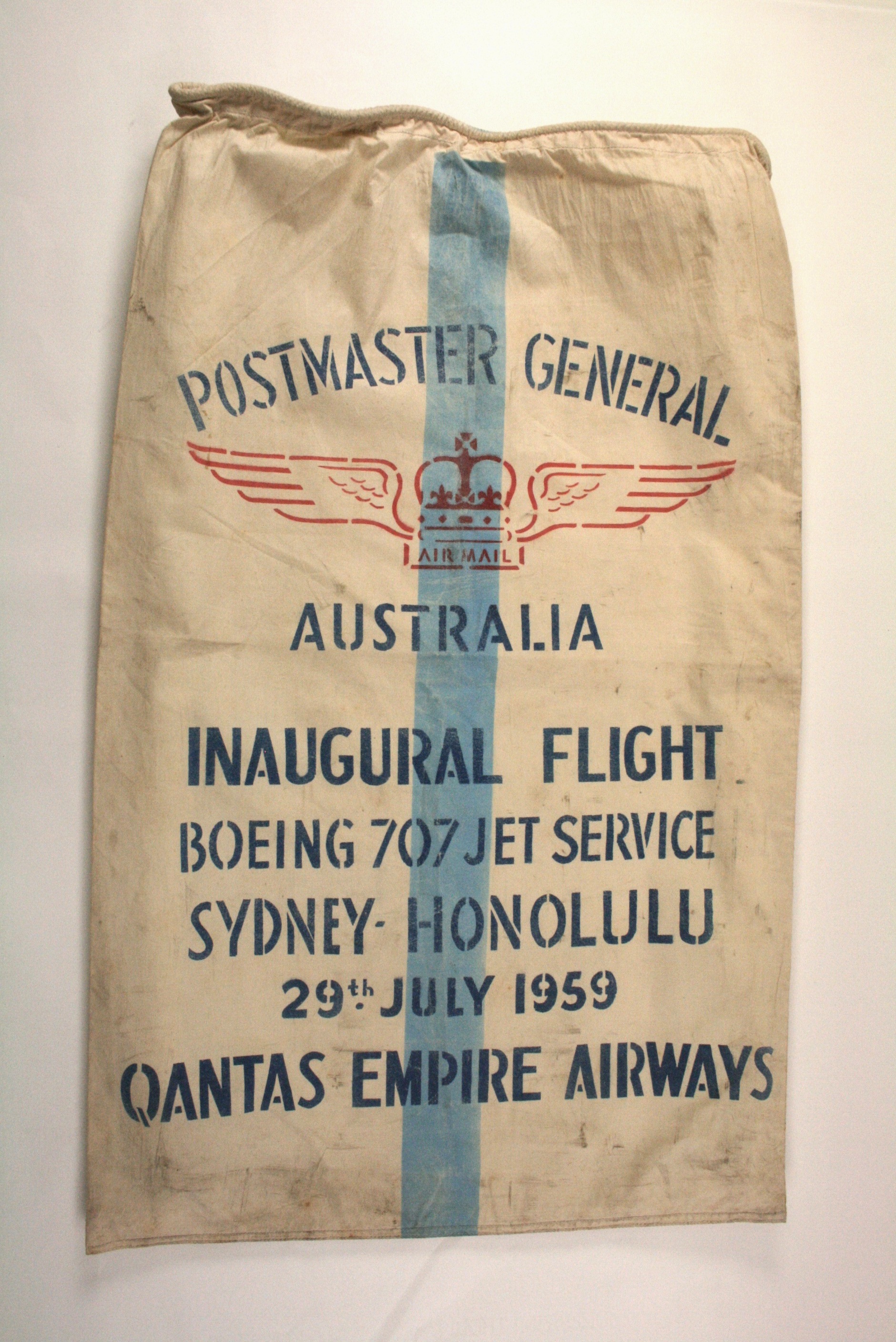

In 1940, Pan American Airways inaugurated a service from Sydney to Auckland, San Francisco, New York, Lisbon and England. British Commonwealth Pacific Airlines (BCPA) operated a service from Sydney to Vancouver in competition with Pan Am from 1946. In 1949, BCPA launched a new fleet of DC6 aircraft for the trans-Pacific service, with Charles Ulm’s son, John, a passenger for the maiden flight of ‘Discovery’.

The trans-Pacific service was taken over by Qantas Empire Airways (QEA) in 1954, and from 1959 was operated with Qantas’ first fleet of Boeing jet aircraft. Two decades after Ulm’s tragic disappearance, flights across the Pacific Ocean had become the commercial reality that Ulm envisaged.

Ulm’s RAAF uniform cane and a commemorative airmail box, from Ulm’s flight to New Zealand in December 1933, are on display in the Museum’s new acquisitions showcase until 23 August 2015.

For more information: www.nma.gov.au/collection/highlights/aviation

Feature image: Article in a scrapbook of newspaper clippings in the National Museum’s collection, compiled by Jo Ulm, following her husband’s work and the search for ‘Stella Australis’ and crew. Austin Byrne collection.

Very fascinating article on an event that I knew nothing about. It’s amazing to read about these early pioneers and the risks they took for things we take for granted today.