Domestic to industrial

Water enables so many tasks in the world that sometimes, we can forget how essential it is. At the domestic level we use water to drink, cook with, clean ourselves and our clothes and to keep our gardens growing. Industrially, water is a vital input to many industries but perhaps the most well recognised is the agricultural industry. This post takes a look at two objects, relating to the home laundry and the development of large scale agriculture, as a means of exploring this spectrum of domestic to industrial.

Clothes pegs

We often don’t think too much about domestic objects that we routinely use. They’re there, they make our life easier, but that’s about it. The humble clothes peg is just such an item. It’s just a thing we use to get through our daily life, helping us to make sure we have clean presentable clothes to face the world in. You might also think that clothes pegs are so simple and so obvious that they have been around forever. They haven’t. Clothes pegs are quite new to human history.

The Museum’s pegs came from the Bothwell Museum, a small museum near New Norfolk in Tasmania, which was devoted to domestic items. When it was forced to close, the Museum acquired a number of objects, including these pegs. Of the pegs shown here, we can identify two properly. The largest peg was made by Mrs One-Eye Brown, a hawker/traveller in Tasmania in the 1930s. Her pegs were crafted by hand from willow, and were part of Mrs Brown’s attempts to get enough food together to eat in the days before social security. The next largest peg is a dolly peg, were made from sassafras wood. It came from the Pioneer Peg factory at New Norfolk, which opened in 1929. It was the only peg factory in Australia and operated until 1975. According to the local newspaper, its closure was prompted by equal wages for women and imports from China.

There are three main hypotheses about the origin of pegs. The first is that they are of Shaker origin. The Shakers were a religious group in colonial America. Part of their faith in God involved what we might now call minimalism. Shakers did not eschew material things, but nor did they value accumulation, and what they did make had to be functional, durable and beautiful. Shaker furniture is now highly collectible. Read more about the Shakers and their furniture.

A second possibility is that pegs derived from sailing traditions, where sailors pegged items onto the rigging. The third theory of origin is that pegs were made by travelling gypsies around Europe, and they formed a way to trade for things that they needed. Mrs Brown’s experience would seem to support the ‘gypsy’ theory, and reminiscences about Mrs Brown suggest that her behavior conformed to the stereotype.

The only certain and dateable evidence of the invention of the clothes peg is the patent granted to David M Smith of Vermont in 1853. While there was an earlier patent granted, the details have been lost in a fire at the patent office. So, David Smith’s invention of the two halves clothes peg operated with a spring is usually claimed as the first. However, it doesn’t answer the question of where he got the idea from. Was it is his own inspiration, or did he merely patent something he had seen and known about for some time? Either way, the clothes peg remains a relatively recent addition to the domestic sphere, along with laundry powder, scrubbing boards, washing machines and clotheslines.

Clothes pegs are part of a broader history of laundry. The most essential part of any laundry day is access to water. For the majority of history, this water had to be carried by hand. Water is heavy! A litre of water weighs one kilogram, so getting enough water to do the laundry was hard labour in itself. It also explains why for centuries, women have preferred to take their washing to the water rather than the water to the washing. This is why the introduction of major water infrastructure, like the next object, was so important.

Water weir

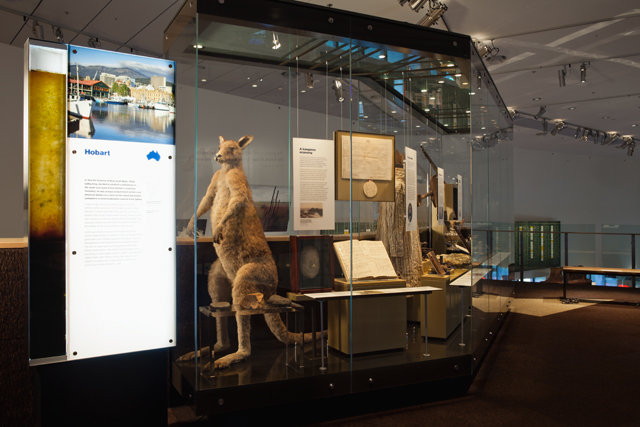

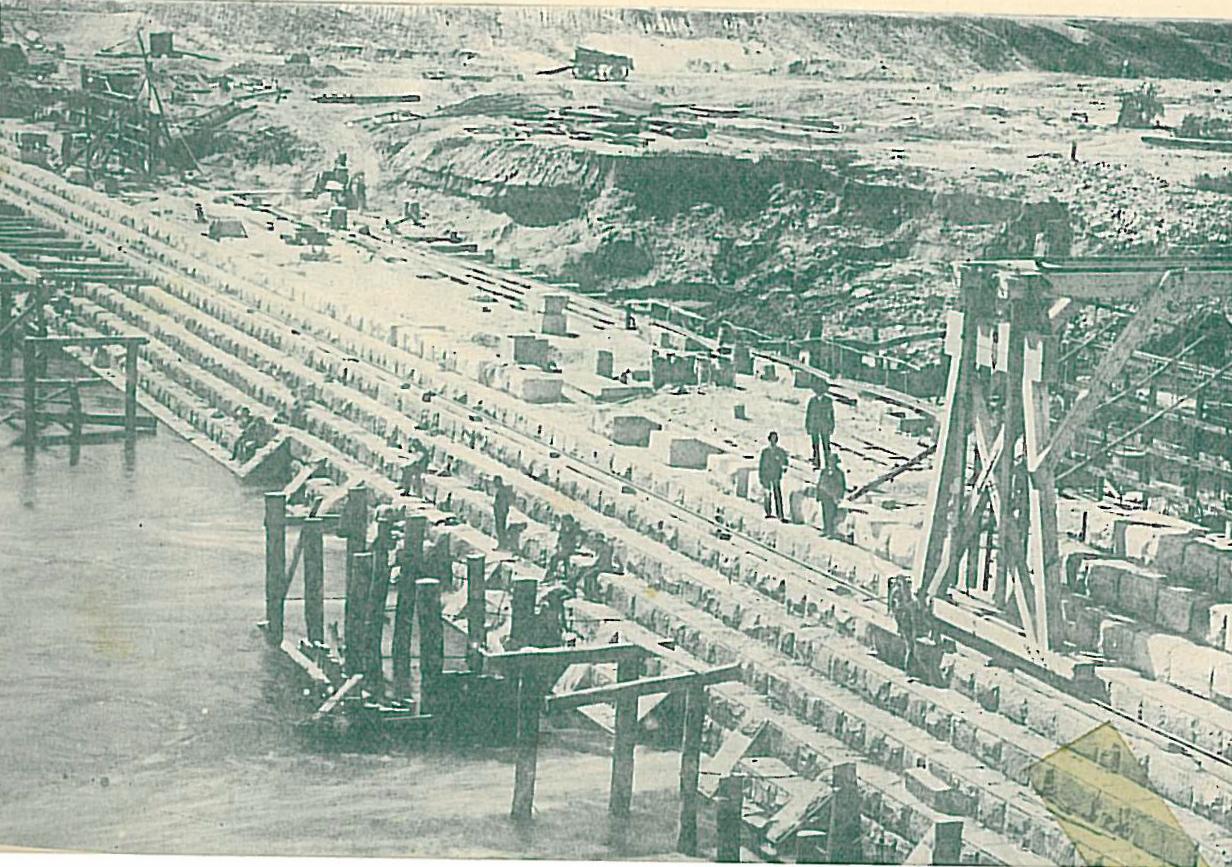

The next object is at the opposite end of the scale from the clothes pegs, being both massive and industrial. It is the remains of original Goulburn Weir, including a length of the dam superstructure, a gate and two piers. Our photos show the weir parts being transported to the National Museum, and give a sense of their size and bulk.

The weir is Australia’s oldest irrigation diversion structure. It was built between 1887 and 1891 by the Victorian Water Supply Department to divert water from the Goulburn River for agricultural and domestic use in northern Victoria.

At the time it was built, Goulburn Weir was considered an engineering marvel. Visitors came from all over Victoria to look at the steady, bright electric light generated by the hydro-electric turbines. People enjoyed the play of light on the water spray at night, and the weir became the site of recreational and social activities. The weir was widely reported in the colonial press, both locally in Victoria and in other colonies. The weir was so well known that in 1913, the Commonwealth of Australia chose it go on its new currency. Lake Nagambie, created by Goulburn Weir, has developed as a recreational venue for water-skiing and rowing regattas.

While a first for Australia, the Goulburn Weir is simply one more example of a nine thousand year old pattern of water control. Control of water was the foundation for the Egyptian, Mespotamian, Indic, Chinese, Andean and MesoAmerican civilizations over the last 9000 years. Most of this water use was for irrigation (MacNeill, Under the Sun, p. 120). Well known environmental historian John MacNeill remarked that dams are symbols of power. More specifically, he pointed to a mentality among leaders that used massive water engineering projects to lend themselves political credibility. He writes that:

A great deal has changed in the hydrosphere because of men who felt much the same way that Churchill did [namely, that it would be ‘fun’ to make the Nile start in a turbine]. Lenin, Franklin Roosevelt, Nehru, Deng Xiaoping and a host of lesser figures saw water in much the same way…They did so because they all lived in an age which states and societies regarded adjustments to nature’s hydrology as a route to greater power or prosperity. And they had unprecedented technical means at their disposal. Since 1850 hydraulic engineers and their political masters have reconfigured the planet’s plumbing. They did so to accommodate the needs of the evolving economy, but also for reasons of public health, geopolitics, pork barrel politics, symbolic politics and no doubt to satisfy their vanity and playfulness (p. 150).

MacNeill went onto note that while change was the desired outcome of hydrological manipulation, sometimes they didn’t always get the change they wanted. Setting aside any social ramifications, there are a whole range of unintended ecological consequences from large scale water manipulation, many of which are slow to emerge and hard to reverse. For example in Australia, which has one of the most variable hydrological cycles, river regulation seeks to stop variability. This is helpful for creating stable and predictable conditions for crop growth. For native species which have evolved to cope with variability, it is not. The removal of variability from river systems endangers the integrity of whole vegetation complexes.

This fundamental tension between the desire for permanency and stability and the actual fluctuations of water has been a significant driver of water policy in Australia. The Goulburn Weir was approved following severe drought and its water was used to supply local towns for domestic purposes, and to support the agricultural industry. This was a major boost to the social and economic growth of the area. The public reception of Goulburn Weir is indicative of twin beliefs that were widespread in the nineteenth century; that technology lead to progress and that there were no limits to growth.

Colonial Australians believed to a much greater extent than contemporary Australians that there was no environmental issue that couldn’t be solved with human ingenuity. The nineteenth century was an era of significant engineering developments which in many ways made the modern world. Clean, distributed water is one of those developments. The Goulburn Weir set in motion a change to our social and ecological world that continues on.

More

This blog post is the second essay in my series on the history and culture of water in Australia. Read my third essay, ‘A tale of extremes’.

References

McNeill, J.R., Something New Under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth Century World, WW Norton and Co, New York and London, 2000, paperback edition in 2001.

Further information

‘Who made that clothespin?’ The New York Times Magazine

This image from the State Library of Tasmania shows the pegs and their original packaging.

Clothes pegs, Powerhouse Museum