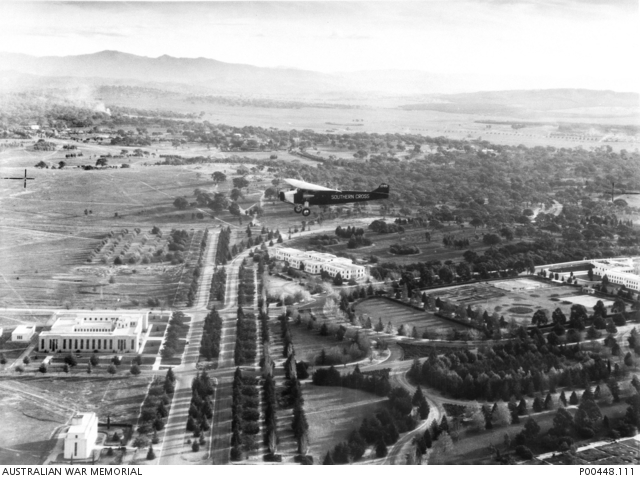

‘Southern Cross’ arrives in Brisbane: the nation celebrates

When the ‘Southern Cross’ touched down at Eagle Farm aerodrome in Brisbane on 9 June 1928, tens of thousands of people turned out to greet the triumphant aviators after their trans-Pacific journey. Throughout the flight, the crew had maintained continuous radio contact with the world, assisting their safe passage, but also allowing the public to share in their endeavours. By the time they arrived in Australia, the feats of Charles Ulm and Charles Kingsford Smith were well-known and the nation celebrated their achievements. Challenges and criticisms came quickly, however, and some of the shine was soon taken off their glowing success.

A Brisbane welcome

As the crew climbed out of the ‘Southern Cross’, tired and disheveled from their arduous flight, their spirits were buoyed by the cheers that greeted them. Ulm and Kingsford Smith recalled:

“We stepped from the cockpit into a surging press of people, who all seemed to want to shake hands with us at the same moment. A lady broke through the crowd and decorated Kingsford Smith with a garland of roses. Then we were swept off our feet, and carried shoulder high to a motor car before the Qantas hangar.” [1]

The crowd spread from the aerodrome into the city centre, as Ulm, Kingsford Smith, Lyon and Warner were driven to a civic reception at City Hall. The crew received messages of congratulations from across Australia and the world. A message from Prime Minister Bruce, read by acting Lord Mayor Watson, offered congratulations on behalf of the people of the Commonwealth. Queensland Governor Sir John Goodwin remarked that the flight was more than a personal triumph, because it marked, as well, a new era in aviation. [2] On their arrival in Australia, Ulm and Kingsford Smith also received a telegram from their generous benefactor, Allan Hancock, informing them that he had released them of their debts to him, and ownership of the ‘Southern Cross’ was transferred to them.

Celebrations in Sydney

With their success now secured, Ulm, Kingsford Smith, Lyon and Warner flew on to Sydney, where their official reception had been planned. On the afternoon of Sunday 10 June, the scene at Mascot aerodrome from the air was something to behold:

“A solidly-wedged mass of humanity covered acres on each side of the main hangar, and every road leading to the aerodrome was choked with motor cars, and a vast army of people hurrying to the flying ground on foot… In fact, to look down from the cockpit on that shifting ocean of heads that swept this way and that, inspired one with a certain amount of awe.” [3]

Estimates on the size of the crowd at Mascot that day ranged from 100,000 to 300,000 people, with many more stranded amongst the heavy traffic chaos that the gathering had caused. On this occasion, the crew found the roar of the crowd louder than the ‘Southern Cross’ engines. A young Ellen Rogers, who would begin working with Ulm and Kingsford Smith during the following days, described the scene in Sydney that afternoon:

“I felt I had to get out to the aerodrome at Mascot to see the arrival. A friend and I caught a Botany tram from the city to take us as far as possible to our destination. However, the traffic was so congested that the trams were at a standstill and we decided to get out and walk. We took short cuts through the Chinese market gardens, but even then we were too late – the plane had already landed and was surrounded by thousands of people.” [4]

Reaping the rewards

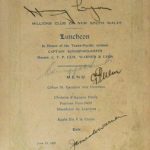

The crew were showered in accolades, and during the following days and weeks they were entertained and congratulated by political, community and business leaders at many luncheons, dinners and other special events held in their honour. As they continued on to receptions in Melbourne and then Canberra, many gifts were bestowed upon them, and Ulm and Kingsford Smith used those opportunities to express their gratitude and outline their future ambitions.

They had left California heavily in debt, and so it was a relief when some of the gifts they received were financial. Within days, grants of £7,000 from the New South Wales government, £5,000 from the Commonwealth government and other private pledges to the airmen had been announced.

At a luncheon held by the ‘Sun’ newspaper, which had supported the aviators from the beginnings of their trans-Pacific plans, Ulm stated, “Everyone is doing all they can for us. What can we do in return? I think we can respond by, in some little way, furthering the cause of aviation… We have the finest flying country in the world… Smithy and I will never give up flying”. [5]

Ulm and Kingsford Smith became instant celebrities, and the association of their names with their flight sponsors and other companies and products began to pay dividends. When Ulm and Kingsford Smith purchased new Studebaker sedans in July 1928, the company publicised the airmen’s endorsement of their vehicles, as the “co-commanders of the ‘Southern Cross’, who conquered the Pacific by air, know their job; know engines and engine performance thoroughly”. [6]

Building on their success

American crew members Lyon and Warner returned home at the end of June, and Ulm and Kingsford Smith began their plans for future flights and a new aviation company. Their successes in flying around Australia and crossing the Pacific Ocean were quickly followed by the first non-stop flight from Melbourne to Perth in August, and across the Tasman Sea to New Zealand in September. The flights earned them sufficient public confidence in the possibilities of commercial aviation in Australia. In December 1928, Ulm and Kingsford Smith established Australian National Airways Ltd, supported by public subscriptions without the need for any government subsidies.

Ulm and Kingsford Smith were supported in their work by secretary Ellen Rogers, then working with Atlantic Union Oil Company in their support of the aviators following their use of Atlantic oil and fuel on the trans-Pacific flight. They approached the directors of Atlantic to seek release of Rogers so they could employ her in their new company. She began working as secretary to Ulm and Kingsford Smith, one of the first employees of Australian National Airways, as they began the process of purchasing suitable aircraft and constructing a hangar at Mascot aerodrome.

From heroes to villans

Based on the success of their exploits in the Fokker tri-motor ‘Southern Cross’, Ulm and Kingsford Smith ordered five tri-motor Avro X (Ten) aircraft from A V Roe and Co in England for Australian National Airways; naming them ‘Southern Cloud’, ‘Southern Star’, ‘Southern Sky’, ‘Southern Moon’ and ‘Southern Sun’. The Avro X aircraft were A V Roe’s version of the Fokker FVII-3M, manufactured under licence from Fokker.

Kingsford Smith and Ulm decided to fly to England in the ‘Southern Cross’ in 1929 to survey future routes for air services, inspect their fleet of Avro X aircraft under construction, and engage pilots, engineers and support for their venture. Disoriented in heavy weather, they were forced to make an emergency landing north of Derby, Western Australia. With their radio damaged, aerial search parties were sent to find the ‘Southern Cross’ and crew. The ‘Kookaburra’, one of the aircraft involved in the search, crashed during the search, killing aviators Keith Anderson and Bob Hitchcock. Although Kingsford Smith and Ulm were rescued and eventually continued to England, the inquiry into the forced landings and crash damaged their reputations. Kingsford Smith and Ulm were accused of staging the forced landing to gain publicity and questioned at length about their flight preparations, navigation and the condition of the ‘Southern Cross’.

Ulm returned to Australia for the inaugural flights of Australian National Airways (ANA) in January 1930. In March 1930, Ulm sold his share in the ‘Southern Cross’ to Kingsford Smith and took on a greater role in managing ANA, rather than joining the next leg of the planned ‘Southern Cross’ around the world flight across the Atlantic Ocean. Kingsford Smith successfully piloted the ‘Southern Cross’ across the Atlantic and then to New York and San Francisco. Further flights were made before Kingsford Smith retired the ‘Old Bus’.

Final journey of the ‘Southern Cross’

On 18 July 1935, Kingsford Smith gifted ‘Southern Cross’ to the nation in a ceremony at Richmond aerodrome. It was held in storage for decades, briefly reappearing for restoration work and use in the 1946 film ‘Smithy’, before a 1955 Federal cabinet decision gifted the historic aircraft to the state of Queensland in recognition of Kingsford Smith’s birth place in Brisbane. In 1958, as part of the 30th anniversary of the trans-Pacific flight, the Sir Charles Kingsford Smith Memorial building, housing the ‘Southern Cross’, was opened at Brisbane airport. Surviving crew members, Harry Lyon and James Warner attended the celebrations, organised by Charles Ulm’s son John.

[1] Kingsford Smith and Ulm, Story of ‘Southern Cross’ trans-Pacific flight 1928, Penlington and Somerville, Sydney, 1928, p215.

[2] Kingsford Smith and Ulm, Story of ‘Southern Cross’ trans-Pacific flight 1928, p216-217.

[3] Kingsford Smith and Ulm, Story of ‘Southern Cross’ trans-Pacific flight 1928, p221-222.

[4] Ellen Rogers, Faith in Australia: Charles Ulm and Australian aviation, p28.

[5] Ellen Rogers, Faith in Australia, p29.

[6] ‘Put wings on it’, in The Gosford Times and Wyong District Advocate, 16 August 1928, p15.

Ulm’s RAAF uniform cane and a commemorative airmail box, from Ulm’s flight to New Zealand in December 1933, are on display in the Museum’s new acquisitions showcase until 23 August 2015.

For more information: www.nma.gov.au/collection/highlights/aviation

Feature image: ‘Southern Cross’ arrives in Brisbane, 9 June 1928. Austin Byrne collection, National Museum of Australia.