Making 'Silent Conversation'

At the heart of the Spirited: Australia’s horse story exhibition is the question ‘how has the connection between horses and humans shaped life this country?’

Our research into Australia’s horse history has revealed many complex and profound human responses to horses. We also want visitors to consider the other side of that connection – how do horses think and feel about us?

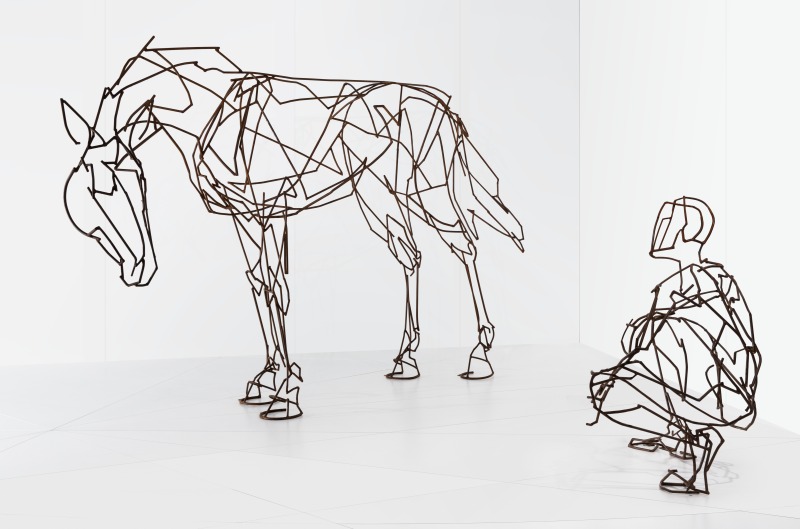

At the centre of the exhibition is a meditation in steel on the horse/human bond – artist Harrie Fasher’s sculpture ‘Silent Conversation’.

Photograph by Jason McCarthy and George Serras

National Museum of Australia

The sculpture features two figures, one horse, one human, contemplating one another.

So how did ‘Silent Conversation’ come to be?

In 2013, when we were just beginning research on the Horses in Australia project, we came across a magazine article about artist Harrie Fasher, and her journey from professional equestrian to horse sculptor. Horses had always been Fasher’s passion. She grew up at Wilberforce near Sydney, and rode with her sisters and cousins. “All parents hope their child will grow out of having a crush on horses, but mine just got thicker and thicker,” she told Catherine McCormack. “I lived in this euphoric world of horse — I’d always be galloping and jumping in my mind.”

Fasher became a professional three-day eventer, until a major accident in 2003 left her with a broken pelvis and spinal injuries. Her grey horse Gallagher died. “I feel like one of us had to go, just the way we fell,” Fasher told journalist Elizabeth Fortescue. “I feel eternally grateful for that horse to have given his life for me.”

In the months the followed, Fasher realised her serious riding days were over. She decided to pursue art instead, beginning a degree at National Art School in Sydney. Enrolling in painting, she was soon drawn to the physicality of sculpture. ‘There is an energy created when you physically battle with an object’ she told Horsezone in 2011. ‘This energy becomes a whirlwind, it is really a bit of a rush.’

Fasher works intuitively, bending and welding steel rod to make her works, which often feature horses. She told Australian Country Style: ‘I tried to avoid it, but it is a part of who I am. I think my spirit is that of a horse, which is why it made sense to tell a narrative with the horse’s form. The horse is a symbol of power and strength and elegance, but it’s also fragile. That’s the juxtaposition I explore in my sculpture.’

Photograph by Jason McCarthy

National Museum of Australia

People and the Environment Head Curator Kirsten Wehner and I met with Harrie at the Museum late in 2013. We were keen to include one of her sculptures in the exhibition, and we talked about the works she had already created for a wide range of exhibitions, prizes and residencies. We discussed what has made the horse such a powerful presence in art, over many hundreds of years.

Following our meeting, we began to see a place for Harrie’s signature steel-rod linework in the suite of horse and human mannequins needed to support the saddlery, harness, vehicles and clothing featured in the exhibition. This involved realising the forms of specific horses, based on archival images, meticulous object measurements, and Harrie’s deep understanding of horse anatomy and movement. The mannequins were designed by Harrie, and realized by her and Thylacine Exhibition Preparation. Many of the exhibition’s visitors have commented that it seems as though the horses move as you walk around them, their forms are so dynamic and full of character.

While the forms of real horses now had real presence in the show, there was still something missing – a central work that spoke to the unique qualities of both horses and people, and to the bonds that bridge across the differences between the two species. Early in 2014 we began talking to Harrie about a commissioned piece that would explore this relationship. We discussed a work that showed a horse and a person approaching each other, perhaps for the first time, perhaps part of the daily ritual of meeting together in the paddock or the stables. Harrie described going to collect one of her mares, who always shows a bit of spunk whenever Harrie goes to get her: the toss of her mane, a dash and a buck signalling her feisty independence, before she’ll trot down willingly. The piece needed to have something of that spiritedness in it, but also something of the generosity and willingness required on both sides to make the connection work.

Harrie worked up a number of ideas, and we to-ed and fro-ed with sketches and wire maquettes for a while, until she hit on the title, ‘Silent Conversation’, and then the idea of having the human figure squat down. At that point we knew she’d captured the balance and respectfulness of two very different creatures recognising each other’s strength, gentleness and curiosity about each other.

Harrie and assistant steel fabricator Nicole O’Regan then set to work to realise the sculpture at life-size. They spent hours in Harrie’s studio at Oberon, cutting, filing and bending the steel rod, and welding it into place. Harrie would then ‘sit’ with the sculpture for a while to see what was working and what wasn’t – and how her own body related to the horse’s body. Numerous times Harrie took to the two figures with an angle grinder, cutting away parts that were not true-to-form, and then rebuilding them with new rod. ‘It’s a battle of wills making a sculpture’ she told us. Drawing was a key tool in resolving difficulties, with quick sketches offering new ways to resolve ‘where the weight is in the figure, where the muscular structure comes into the form’.

The Museum commissioned Marg Hogan from Red Moon Creative, a graphic design/communication studio based on Bathurst, New South Wales, to document the making of ‘Silent Conversation’. Marg produced a short film showing Harrie at work, featuring the music of Pia Jane Bijkerk. You can view the film on the Museum’s You Tube channel here.

The completed work arrived at the National Museum of Australia’s loading dock on a truck in early September 2014. Harrie arrived soon afterwards, and supervised the sculpture’s installation into the exhibition’s central hub – a white oval plinth framed by a white wall and archway. The effect was, for me, breathtaking. It felt as though the whole exhibition had finally been completed by this deep reflection on the mysterious bond that has connected horses and humans for millennia.

After install, Harrie returned home to Oberon to make her next major work, a two-headed rocking horse for Sydney’s Sculpture by the Sea, and afternoons of sketching on horseback with her equine friends Evie and Dusty.

Photograph by Margaret Hogan, Red Moon Creative

She also has her herd of sculptured horses, though they demand a little less attention. ‘I am still surrounded by horses’ she says, ‘but they are quiet, and don’t need rugging.’

In Canberra, visitors to the exhibition stand enthralled in front of ‘Silent Conversation’ – the latest addition to the Museum’s stable. It’s clear the work has touched a chord with people. Many stand and gaze at the two figures for a long time. Others walk around it, letting the lines of the two figures mix and merge with one another. I imagine many of them are remembering a similar moment of connection with a special horse from their own lives, and the ‘silent conversation’ they’ve shared with each other.

——————-

What are your responses to Harrie Fasher’s sculpture ‘Silent Conversation’? You can leave your comments below.

——————-

Some of this text has also appeared in the November 2014 issue of Horses and People magazine.