Stories for Healing

‘the cultural paradigm is both the most obvious and the least developed in fire research’

Stephen J. Pyne 2007

International Journal of Wildland Fire, 16: 273

‘The mechanisms of storytelling… are our best hope of building a more inclusive and a more responsible citizenship’

Quentin Bryce, ABC Boyer Lectures, 2013

The Victorian Bushfire Project 2009-2013

The Victorian Bushfire Project began with an unexpected story, and it has been fuelled by more and more surprising stories since. Telling true stories has been the route to the future for the people of Steels Creek, a small hamlet in a valley where the fires of Black Saturday (7 February 2009) took 10 lives and 67 homes. In the immediate aftershock, where everyone was grieving for the loss of family, friends and the neighbourhood they knew, Malcolm and Jane Calder, whose home miraculously survived in the heart of the valley, found themselves passing an essay around the blackened valley. In ‘They still had not lived long enough’, published in Inside Story just days after the fire, Tom Griffiths asked why we had not been able to learn from the 1939 fires which swept through the same area, and why we still failed to save lives. The Calders found this essay provided a tool that enabled the community to start talking, to overcome the horrified silence of the aftermath. Three months later Malcolm and Jane Calder, on behalf of the Steels Creek community, formally approached Tom with the idea that the community wanted to understand its history. It needed to know more fully what it had lost in order to move forward. It needed history to rebuild.

The Bushfire Project has been four years in the making. The Victorian Government, through its Victorian Bushfire Reconstruction and Recovery Authority offered fire-affected communities some funding to support rebuilding, and part of this was what the Steels Creek community used to seed the Bushfire Project, a partnership in history and story-telling with the Australian National University and the National Museum of Australia. The project grew through the generosity of the Myer Foundation, the Thomas Foundation and other philanthropists. Even the essay itself had a hand. In September 2009 it won the Alfred Deakin Prize for an Essay Advancing Public Debate at the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards, and Tom Griffiths immediately donated the $15,000 prize money to support the project.

First there were two books, Christine Hansen and Tom Griffiths’ Living with Fire (CSIRO Publishing 2012) and Peter Stanley’s Black Saturday at Steels Creek (Scribe 2013). The final culmination was Moira Fahy’s documentary film, Afterburn: In the Tiger’s Jaws (One Thousand Productions 2013), launched on 9 December 2013.

Moira Fahy, Afterburn filmmaker, and Tom Griffiths. Photo: Libby Robin.

Moira Fahy, Afterburn filmmaker, and Tom Griffiths. Photo: Libby Robin.

Afterburn

The launch was hosted at the Melbourne Museum by Craig Lapsley, Victoria’s Fire Commissioner. The Melbourne Museum’s Forest Gallery holds a moving memorial to all the communities affected by the 2009 fires: a burnt red brick standing chimney, a symbol of the many houses lost. The Forest Gallery curator, Luke Simpkin, has been another creative researcher of Australia’s fire flume communities, particularly those dwelling in the shadow of the giant Mountain Ash trees north-east of Melbourne, which are the focus of the Forest Gallery.

Fahy and Lapsley. Photo: Libby Robin.

Bushfires go down in history as single days: Black Thursday 1851, Black Friday 1939, Ash Wednesday 1983, Black Saturday 2009. The film acknowledges this history of fires, but its focus is on the Afterburn, the word of Moira Fahy, the project’s film-maker. Such a terrible event leaves a long psychological legacy of those fires into the future, and it is this that the film explores through the lives of three families. There has been much discussion of the fire policy to ‘stay or go’ on the day of a fire, but this film explores the bigger question whether to ‘stay or go’ after the event: do you rebuild and begin again, or do you move on? This is a stressful and long-drawn out question that haunts the months and years that follow such a fire.

The whole project is about history, but it is also about transformed lives, about living with fire. It is a history of the future as well as the past. Fires are part of cultural and emotional life in this very ecologically distinctive region. Afterburn offers a new and original analysis, not so much of the fire, but rather of the phoenix.

Local MLA Cindy McLeish, Member for Seymour, and Malcolm Calder. Photo: Libby Robin.

Malcolm Calder opened proceedings with a moving speech on behalf of the Steels Creek community. Malcolm and Jane Calder were one of the three families whose lives since the fire have been followed and filmed by Moira Fahy, so Malcolm represented more than just the community as a whole: his personal engagement with the film and his courage in speaking to a camera is fundamental to the power of Afterburn.

The community. Photo: Libby Robin.

Listening for policy and emotional insight

Tom Griffiths formally launched the film with a plea for putting stories first. He reflected that ‘when administrative departments work with human communities, stories sometimes come last, instead of first; they are used to sell policy instead of to develop it; they are invented instead of researched’. Afterburn suggested a different approach:

“Listening carefully and compassionately, committing yourself to a story you don’t know the end of, actually finding out what happened, how people think and feel, learning how individuals search for meaning and understanding – these are demanding and important tasks that take time, energy, dedication and great skill. These enquiries discover the organic links between people and policy. Researching and presenting the experience of living and witnessing is hard work. It is highly qualified work and it is poorly paid, and it is done only by those who are called to it by conscience and commitment. Today we honour the film-maker Moira Fahy for two decades of such commitment, for believing that telling the human experience of fire and its aftermath will help people to heal, give communities wisdom, improve government policy and save and strengthen future lives.”

Stories for healing are painful to tell. The families who agreed to be filmed, starting just three months after the fires, share their rocky journeys through the ‘afterburn’ of Black Saturday. The deepest trauma may not come from the disastrous day, when adrenalin drives the action, as Dr Robert Gordon, the psychologist featured in the film explains. Rather it comes from the long stress of subsequent decisions (to rebuild or move out?), from the long tail of grief for what was lost (people, neighbourhoods, homes, favorite bush haunts), and from the pain of personal psychological transformation wrought by the fire. The film is a deep and personal partnership between the families, the film-maker, Moira Fahy and the cinematographer Rob Buckell. Managing real emotional tension makes this an exceptional film, one that speaks, not just to the community of Steels Creek, but to the idea of trauma itself, as Moira Fahy explored with Rob Gordon. The fire leaves deep psychological scars that heal differently: individuals and communities all work their way through such traumas personally.

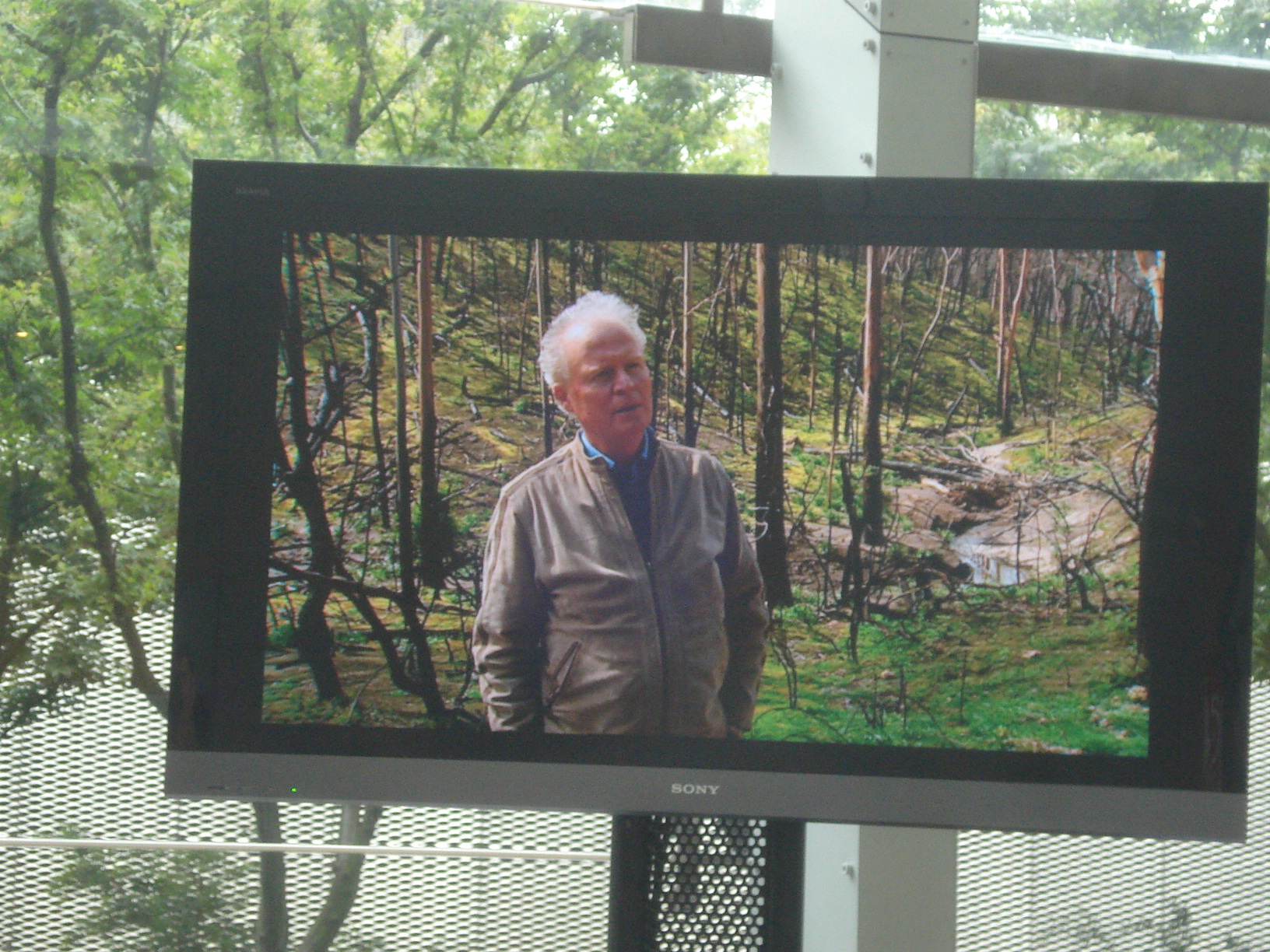

Psychologist Dr Robert Gordon on the ground at Steels Creek. Photo: Libby Robin.

Stories are the basis for healing. Humanism and history are personal, and often overlooked in a research culture where ‘methods’ drive questions, and policy-makers seek solutions to ‘problems’. As Tom Griffiths concluded, ‘we need more research into bushfire that is deeply local, ecologically sensitive and historically informed – and that is undertaken in collaboration with the communities that live with the experience and threat of bushfire and firestorms’. Moira Fahy’s research is powerful in its particularity. Trauma is personal, and it is a privilege to share through her film, these families’ individual struggles as the afterburn continues over four years. The Steels Creek Community is not the same as it was before. Nor are the researchers who participated in this extraordinary partnership.

The Boxed Set arrives in the National Museum of Australia Library. Museum librarians Noellen (left) and Naomi. Photo: Libby Robin.

The Boxed Set arrives in the National Museum of Australia Library. Museum librarians Noellen (left) and Naomi. Photo: Libby Robin.

Further reading

Tom Griffiths, ‘We have still not lived long enough’, Inside Story, 16 February 2009, http://inside.org.au/we-have-still-not-lived-long-enough/

Tom Griffiths, launch of Afterburn, 9 December 2013, http://ceh.environmentalhistory-au-nz.org/research/steels-creek/