Bunya Power

On Thursday morning, as my plane taxied across the tarmac of Canberra airport, thirsty jet engines warming themselves for the flight north, I began reading Ray Kerkhove’s extraordinary document, The Great Bunya Gathering: Early Accounts. This compilation of stories and memories of the bunya trees of southeast Queensland captures and conveys something of the power of these majestic rainforest beings, of their capacities to draw people towards their towering trunks and vast crowns, to feast regularly on their abundant offerings of nutritious and delicious nuts, to celebrate and honour the lively ties that bind and nourish us. As the plane accelerated into the sky, I realised that it was the bunya drawing me northwards, into its shade and story, into the Blackall Ranges of Kabi Kabi country.

We were visiting the Ranges to begin a conversation about the bunya. Was it appropriate to feature this powerful species within our new gallery of environmental history? How might its form and significance find expression within the exhibition? Who can speak for this tree? Might the tree speak for itself?

Through a drizzle of warm rain, Aunty Beverly Hand, bunya custodian and Kabi Kabi woman, led our small group into the rainforest to stand before a giant bunya. Hands on its rippled wet trunk, I noticed drops of moisture gathered on the tiny leaves of epiphitic ferns, glowing like polished green gemstones. One hundred and seventy years ago, Prussian explorer Ludwig Leichhardt experienced ‘a strange feeling of exultation’ in these very forests, and described ‘the majestic tree whose trunk seems like a pillar supporting the vault of Heaven’.

Leichhardt was not the first whitefella to feel and respond to the power and majesty of the bunya. Our host Tamsin Kerr, of the Cooroora Institute, explained that botanist John Bidwill lived in the district a few years before Leichhart passed by. So enamoured of the bunya and its forests was Bidwill that on his discovery of local gold deposits, the botanist kept quiet, fearing the ecological havoc a gold rush would wreak through the Ranges. Sailing home to England in 1841, Bidwill tended bunya seedlings for presentation to Sir William Hooker, Director of the Royal Botanical Gardens. The tree, with an ancient linage that extends back to great Gondwanan rainforests dominated by Araucaria, now carries Bidwill’s name, Araucaria bidwillii. Sturdy bunyas beside old homesteads across southern Australia, and their venerable presence in botanical gardens around the world, record the conifer’s capacities to bind people into tight, responsive relationships.

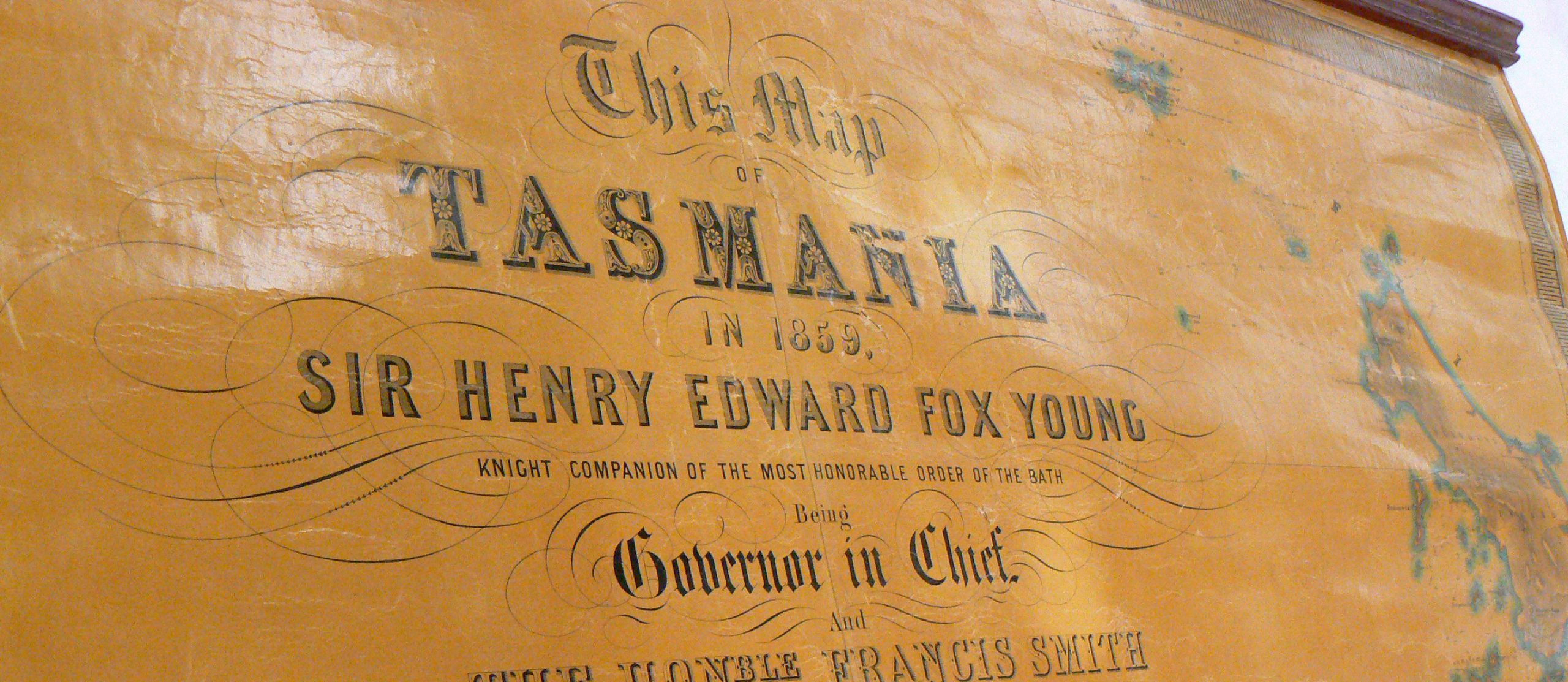

In 1842 the New South Wales government acknowledged the deep significance of bunya to Kabi Kabi clans and other Indigenous groups by prohibiting pastoralism and forestry in the Blackall Ranges. Thousands of people from near and far continued their traditional pilgrimage into the Ranges, drawn by the bunya to feast on their large nuts, to trade and hold ceremonies. On its formation in 1859, the new Queensland Parliament rescinded the protective proclamation. Settlers considered the steep hills and bunya forests a base for terrorism. As war spread, Native Police units targeted the bunya gatherings. By the 1890s, forestry companies had eliminated the bunya forests that once cloaked the Blackall Ranges, and the Bunya Mountains to the west, despite the consistent protests of Indigenous custodians (see Raymond Evans, ‘Against the Grain: Colonialism and the Demise of the Bunya Gatherings’, Queensland Review, vol. 9, no. 2, November 2002).

Driving the twisting roads of the Blackall Ranges, it seemed that perhaps a bunya resurgence was beginning to unfold. Recent plantings of bunya saplings follow fence-lines and farm driveways. The characteristic shapes of bunya trees and cones adorn logos of local businesses. Aunty Beverly is leading the revival of bunya gatherings, a community event she calls Bunya Dreaming. If enough rain has fallen through the Ranges to allow the bunyas to deliver a heavy harvest, the gathering takes place on (or around) the Australia Day public holiday. As we talked with people who knew and loved the bunya tree–those who knew how to germinate and tend bunya seedlings, how to bake bunya nut brownies, how to fell a single bunya tree while maintaining the integrity of an old plantation, how to honour the conifer’s ancient meanings and stories–the cultural energy within human/bunya relationships was palpable.

We recalled our visit last October to Eden, on the coast of southern New South Wales, where longstanding ties between people and whales, and the cultural significance of the migratory pathway of humpback and other baleen whale species, vigorously shape the imaginations and identities of people and a community. There’s a vitality, a valuable power, within these enduring relationships that cross barriers between species. In Australia, human bodies and minds have long been nourished by ties with bunyas, whales, saltwater crocodiles, black swans, Murray cod, red kangaroos, mountain ash, short-finned eels and a myriad of other species. How to honour these relationships within the Museum’s new environmental history gallery, how to represent and convey the form and expressive power of the non-human, how to enable visitors to sense and respond to such powers, are some of the exciting challenges we now face.

Top image: Bunya Mountains National Park, December 2015, Flickr Creative Commons

I love those bunyas. We had one in our garden in Brisbane – far too close to the house. The spiky leaf tips punctured any unwary soccer balls that strayed underneath. The bunya nuts were delicious, though. I have a great recipe involving red cabbage, mushrooms, garlic and bunyas.