Rabbit-proofing the West

The National Museum of Australia holds many different objects that together record the ecological and social significance of the feral European wild rabbit. Recently, curators in the People and the Environment team have looked again at these rabbit items and the fascinating stories they hold. This post is the first in a series co-developed by Jono Lineen and other curators that explores Australians’ experiences with rabbits through objects in the National Museum’s collections.

The European wild rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) has been a particularly successful, damaging and enduring coloniser of Australia’s landscapes. Purposefully released, most notably – though not exclusively – by Thomas Austin on his Victorian property in late 1859, rabbits quickly proved problematic and came to be recognised as a pest. Even with well over a century of attempts at control, rabbits remain; their continued presence is the focus for current invasive species programs and research into improved tools for suppression. In the National Museum’s collections are objects that reflect the many ways in which Australians have sought to ‘deal with’ rabbits: from traps and rifles to various kinds of poison-dispensers. This post is about two comparatively passive-looking objects: segments of wire netting and wood that once formed part of Western Australia’s rabbit-proof fences – a set of three interlinked fence-lines constructed in the early twentieth century with the ambitious aim of excluding rabbits from an entire portion of the continent.

Rabbits on the run

Far and away the most extraordinary example of the state of mind the spread of Rabbits put the people of Australia into, is that associated with the building, at a huge cost, of the Great Barrier Fences in Western Australia. (David G Stead, former Special Rabbit Menace Enquiry Commissioner to the government of New South Wales, writing in 1935.)

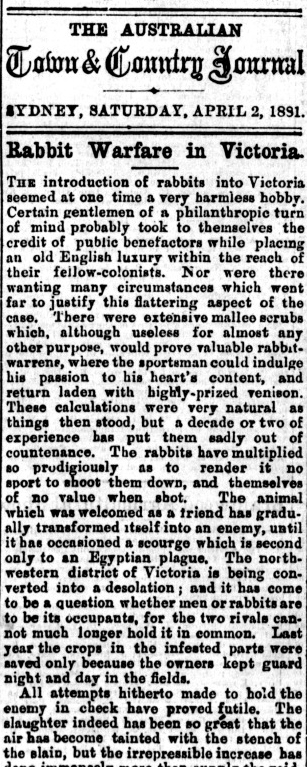

By the 1880s, problems associated with the presence of rabbits had become well known in Australia’s south-east. Rabbits had ruined much profitable farming land through eating and burrowing. Worse still, they had proven frustratingly difficult and labour-intensive to control: populations initially reduced by trapping, shooting, poisoning and warren destruction swiftly recovered. As rabbits began to be noted in new locations and in greater densities, their movement came to be characterised as ‘the advancing menace’ and ‘the grey invasion’. Nothing, it seemed, could halt their spread across the southern colonies. In 1887 the Inter-Colonial Rabbit Commission even sought to offer a £25 000 prize ‘to anyone who could demonstrate a new and effective way of exterminating rabbits.’

With such issues seemingly far away to the east, the Western Australian government responded slowly to reports of rabbits in neighbouring South Australia.

In 1896 the Western Australian Undersecretary for Lands instructed surveyor Arthur Mason to head an expedition into the south-east towards the border with South Australia to investigate. Mason reported that ‘rabbits are travelling and at the rate they are moving will soon overrun the southern portions’. He concluded that a series of fences, one along the border with South Australia and another further west, should be constructed, and optimistically speculated that ‘it would not take long with the assistance of boundary riders, poison, cats, etc. to eradicate the pest’.

Five years later in 1901, a Royal Commission called to ‘Enquire into the Rabbit Question’ tabled its report to the Western Australian parliament and recommended that construction of ‘400 miles of fence … be at once undertaken’. The report further suggested that construction commence in both northerly and southerly directions simultaneously, along with ‘other parties from any other convenient starting points.’ The southern regions contained some of Western Australia’s most productive grazing and farming areas; the experience of Victoria’s western districts had shown how easily rabbits could flourish and wreak havoc in valuable agricultural landscapes.

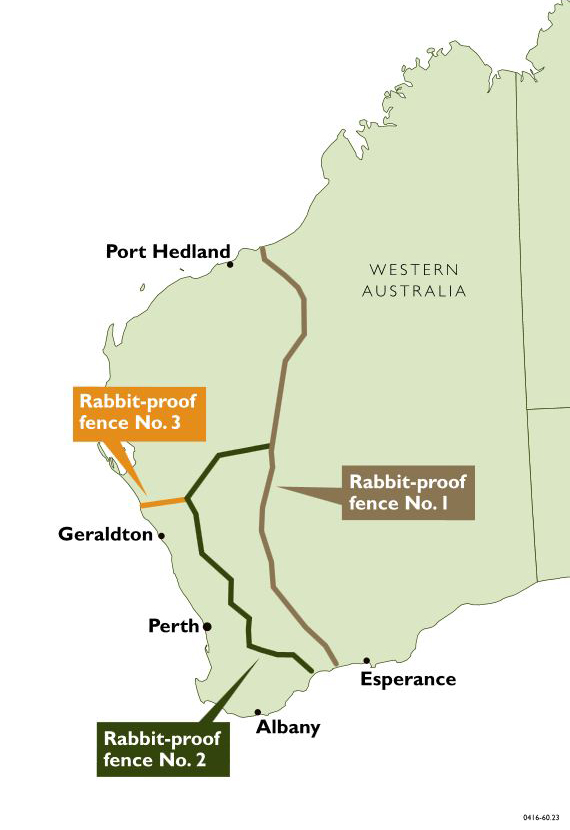

In an immense undertaking, over a 6 year period from 1901 to 1907 an eventual three intersecting fence-lines, numbered 1, 2 and 3, were surveyed and constructed in stages. The finished structures stretched for an astonishing 2023 miles (over 3200 kms) across the Western Australian landscape, spanning the continent between north and south coastlines – an achievement described by former boundary rider and fence historian Frank Broomhall as ’the longest unbroken line of fence in the world’. However as a barrier to rabbits the fences were a failure; even while construction was underway, rabbits were hopping into regions the fences were intended to protect.

Lines of defence

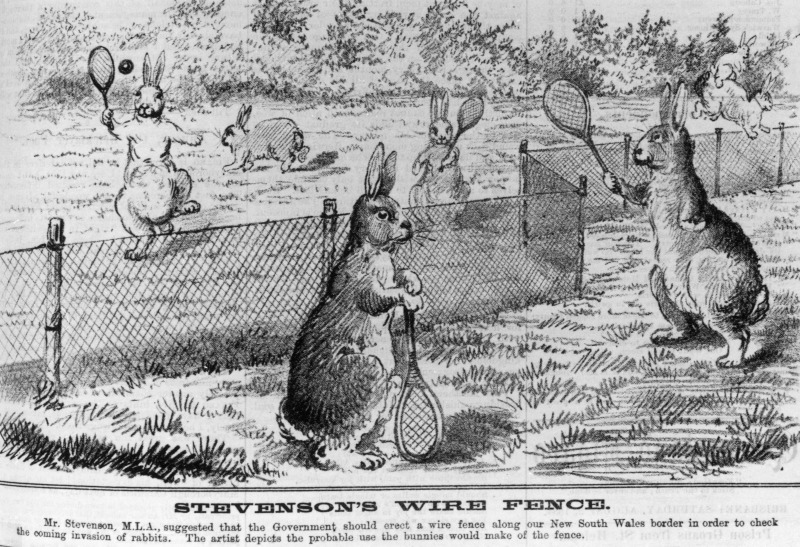

Planners of the Western Australian fences followed the construction of similar long netting fences in New South Wales and Queensland in the 1880s. The first fences that aimed to exclude rabbits from large areas of farmland, these eventually stretched for hundreds of kilometres. Though well-maintained netting fences on a small-scale could be effective rabbit barriers, the same could not be said for longer fences. Besides being costly to erect and maintain, fences often took so long to complete that rabbits could bypass their line ahead of construction. Even vigilantly-maintained fence-lines were still susceptible to breaks which could allow rabbits to pass into areas beyond. As research scientist and writer Dr Brian Coman noted, ‘At best, the long barrier fences merely delayed the spread of rabbits into new country’.

State Library of Queensland, Image no. 185963

Despite such known drawbacks, fencing to protect land from rabbits came to be considered a necessary action. From the 1880s the use of iron wire netting dramatically increased as governments and private landowners began to set up netting fences. Loans and subsidies were made available to landholders to encourage construction of ‘rabbit-proof’ fences on private lands, such fencing later becoming compulsory in some areas. The Pastures Protection Act of 1902 (New South Wales) required landowners to maintain rabbit-proof fencing on their lands or face penalties.

![Providers of wire netting enthusiastically responded to demand from landholders seeking to keep their properties rabbit-free. As this memo from April 1905 in the Museum’s collection shows, Chalmers & Langford ironmonger in Melbourne, Victoria incorporated reassuring imagery of rabbits beside a netting fence on their company stationery. The text reads: ‘Msrs Ramsden & Green/Wangaratta [northern Victoria]/Dear Sirs,/[…] all duly to hand for which we thank/you. We beg to quote the netting you mention […] 36 x ¾ x 20 in 25 yard rolls at the rate of 37/6 per 100 yards or 9/6 per coil. This is really good wire./Promising every attention/We are/Yours faithfully/Chalmers Langford’. Reprography by Sam Birch, National Museum of Australia.](/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/dams_dataprodderiv2jobswm_45806639nma-45806639-015-wm-vs1_o3-1.jpg?w=560)

In the National Museum’s collections

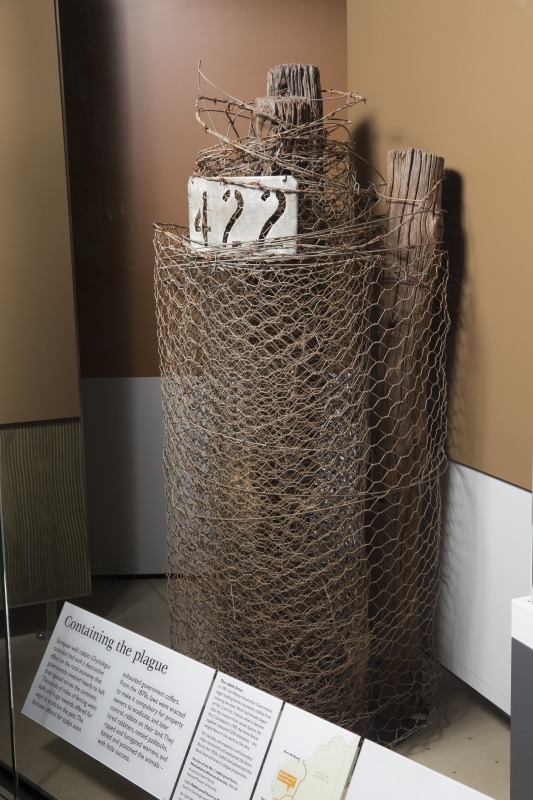

The Museum’s collections contain sections from Western Australia’s No. 1 and No. 2 rabbit-proof fences. Both come from near Meekatharra, a town in the mid-west region of the state, about 771 kilometres northeast of the capital of Perth, and comprise galvanised iron netting attached to deeply weathered wooden posts. Today, these posts have a beautiful, almost fossilised look about them.

The section of the No. 1 Fence was donated to the National Museum in 2000 by the Murchison Regional Vermin Council, the body which today maintains pest-proof fences to protect farmlands in this area. By the 1960s the Western Australian Agricultural Protection Board decided to discontinue maintenance of some sections of the original rabbit-proof fences. In 1963 a group of local shires and landholders, keen to rehabilitate and preserve the fences as a barrier against pest animals such as wild dogs, formed the Murchison Regional Vermin Council (MRVC), and received responsibility for looking after No.1 fence in that area.

On behalf of the MRVC, Kevin Marney organised removal of an original section of fence for the Museum, to be replaced in situ by new materials. Marney was responsible for maintaining 140 miles (about 225 kilometres) of fence line through semi-arid pastoral lease country. His work involved identifying breaks in the fence, replacing rotten posts and repairing the wire. Now rolled, the Museum’s section of No.1 Fence includes a metal plate showing ‘422’, one of many mileage markers set at intervals along the fence line. These markers enabled particular fence sections to be identified, such as when they were in need of repair.

During initial construction, locally-sourced mulga wood – found to be durable when buried in soil – was often used for posts. When needed, Marney replaced these uprights with steel posts, reporting that he had little difficulty sinking the replacement parts. The original builders of this section of fence line had consistently dug standard depth holes, even through stony country, ensuring that the posts sat a uniform 18 inches (45 centimetres) in the ground all along the line.

The Museum’s section of No.2 Rabbit Proof Fence came from near its junction with No.1 Rabbit Proof Fence at Gum Creek Corner, near Meekatharra. It comprises wooden fence posts, 1¼ inch (3.1 cm) galvanised wire netting and plain wire strands with a single line of barbed wire along the top. During construction, posts were closely spaced 12 feet (3.65 metres) apart and netting buried 6 inches (15.2 cm) into the earth to prevent rabbits from burrowing under the fence. The section now held by the Museum was washed away by floods in 1983. It was donated to the National Museum in 1999 by Geoff and Sheila Lacy of Hill View Homestead, Meekatharra.

Surveying the route

The line surveyed by me is the best I could get, and though there are a good many obstacles in the way such as small creeks, hard ground, etc., still a greater part of the line is over really good country in which to erect a fence, and in the remainder there is nothing to prevent a suitable one being erected. (Alfred W. Canning (1860-1936), Report on the route for Fence No.1, 1904)

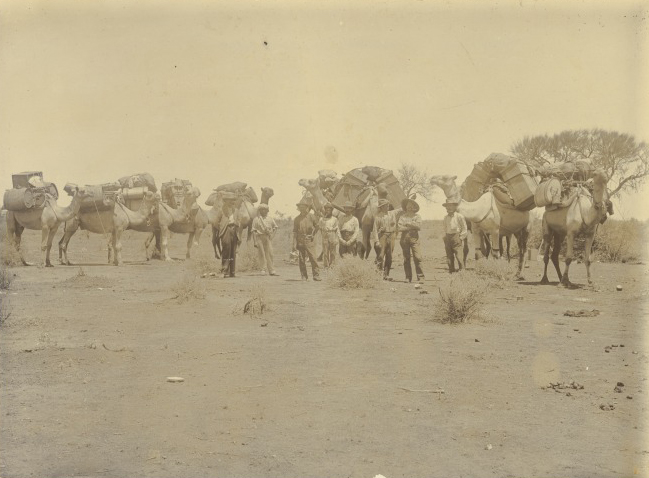

In August 1901 surveyor Alfred Canning, in company with Mr White (a rabbit inspector), an Afghan cameleer, and two other men commenced preliminary examination of the southern end of the line for what would become Rabbit Proof Fence No.1. Canning was to investigate and report on availability of local construction materials, scope terrain to be traversed, and identify any water or feed locations that could assist the parties doing the permanent survey and construction work.

After examination of the country southwards between Burracoppin and the coast, Canning and his small party progressed examination of country to the north in stages (allowing for breaks) navigating their way through remote, at times unmapped and often challenging territory, dealing with heat, unknown or unreliable water-sources, and the loss of camels (used for transport, equipment and provisions) as a result of the animals grazing on toxic plants. Due to such misadventure, on more than one occasion Canning was forced to walk for many miles over several days carrying his own water or instruments.

Secretary Wilson, head of the newly-formed Rabbit Department, later perfunctorily noted of the examination that ‘The result showed a practical route for such a fence, well ahead of the rabbits’.

With the preliminary examination complete, permanent survey then began in earnest. Surveyor General of Western Australia HF Johnston, aware of hardships to be faced, sought and received approval for a special allowance of 15/- per day to be paid to Canning on account of the ‘exceedingly difficult country’.

Canning was still surveying the permanent route north – which he completed in 1905 – when work clearing the ground commenced for the stretch of fence between Burracoppin and the southern coast. The drawn-out nature of construction, however, meant that builders finally reached the Indian Ocean near Cape Keraudren on Western Australia’s north-west coast to finish Rabbit Proof Fence No.1 years later, in September 1907.

Well before this first fence was completed, rapid movement of rabbits prompted swift work on construction of a further two barrier fences – numbers 2 and 3. Finished in 1905, No. 2 Fence ran for 724 miles (1165 km) from Point Ann on the southern coastline, west of and roughly parallel to Fence No.1, which it joined at Gum Creek. No.3 Fence, completed in 1907, ran the short distance of 160 miles (257 km) west from its junction with No.2 Fence near Yalgoo to meet the coast near Geraldton.

Constructing the fence-lines

Building the fences was an ambitious, arduous and slow undertaking. Construction gangs had to traverse a great variety of terrain (rocky, grassy, scrubby, sandy) and endure challenging conditions of heat, cold, dust, flies, and at times, uncertain access to water. Work occurred in stages and section by section; after Canning’s examination of the proposed route, and the survey and pegging of the line, came clearing, then construction of the fence along with gates, rabbit trap yards, maintenance depots and wells to ensure a water supply along the route. Facilities for boundary riders, their animals and equipment also had to be set up.

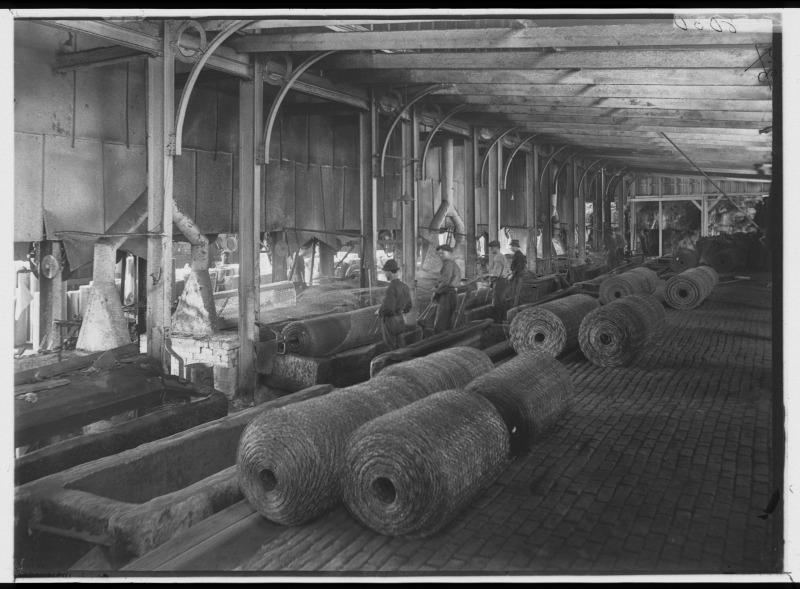

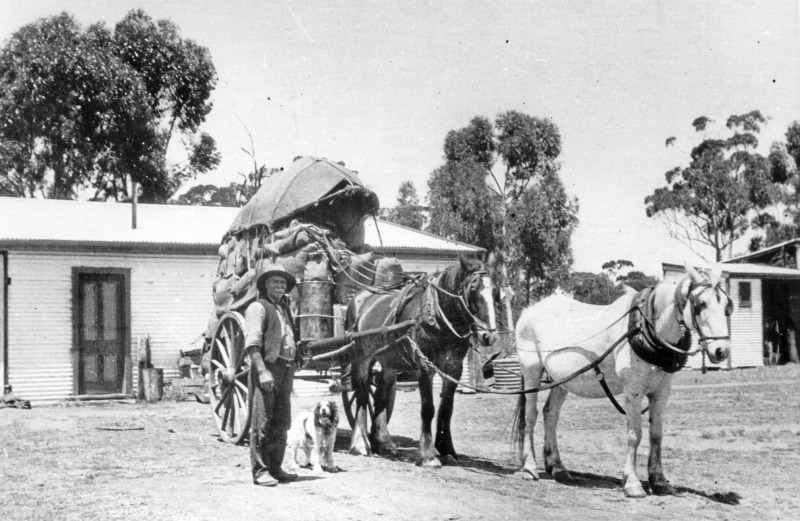

Although some materials, such as wood for posts, could be sourced locally, most had to be hauled hundreds of kilometres from rail heads and ports by bullock, mule and camel teams. In addition, wire, netting and metal posts needed to be imported into Western Australia before being transported out to the fencers. Delays were common and could be significant, such as when supplies of all-important wire netting arrived months behind schedule.

Despite similar specifications, in practice construction materials varied with stretches of fence line at times adapted to suit specific local conditions, such as through the addition of strands of barbed wire or variations in the type and distances between strainer posts and gates.

After construction had finished, in 1908 the Western Australian Public Works Department reported the cost to be an enormous – and not uncontroversial – £337 941. This sum, however, did not include money spent on surveying the routes or significant on-going costs associated with maintenance of the fence-lines. Some observers and newspaper columnists estimated a more likely figure to be well over £400 000.

Writing for The West Australian newspaper soon after the fences’ completion in 1908, AD Boulger wryly observed:

In view of the enormous expenditure on the undertaking, it is reassuring to read the following statement in the recent report of the present Chief Inspector [of] the Agricultural Department:

“The fence as it stands to-day, is as rabbit–proof as the day it was erected.”

Boulger concluded:

[T]he rabbit–proof fence, the work itself, at least, stands as a monument of what human ingenuity and perseverance can accomplish in the face of many and great difficulties.

Maintaining control

Even before they were finished, the fences required an extensive and costly regime of repair due to natural and human forces. Wind storms, sand drifts, flash floods, bush fires, insects and animals (white ants, rats, wombats, kangaroos and emus which chewed, burrowed under, or knocked into, the fences) regularly caused damage which created breaches in the barrier. Additionally, the necessity of gates, as historian J Crawford notes, proved a ‘tremendous weakness’ to the integrity of the fence system, as many were left open or broken. Newspapers regularly published commentary by those supporting the necessary role of the fences and those deriding them as expensive and futile.

Boundary riders working alone or in pairs, patrolled stretches of fence-line mounted on horses, bicycles or camels. Their work was crucial to identifying and fixing breaks in the fences. During the 1940s and into the 50s and 60s, boundary riders adopted trucks, tractors and other available machinery for this task.

Through the early decades of the twentieth century, Australians’ efforts to control rabbits’ movements and numbers were re-focused away from physical barriers and on to biological controls. The Western Australian rabbit-proof fences remained in situ though over the decades large stretches were deliberately abandoned, while others fell into disrepair and dereliction due to high costs and difficulties associated with keeping them viable. Global events including the First World War (1914-1918) and the 1930s Depression limited the availability of men and materials and resulted in long periods during which repairs could not be completed.

Today, sections of the original fence-line are maintained by individual landholders and regional councils who use them to prevent dingos, emus, kangaroos and goats from entering farming country. Western Australia’s current State Barrier Fence incorporates and extends some of the original rabbit-proof fence-lines.

A continuing presence

Besides constricting the movement of rabbits, the fencing had, and continues to have, wider social and ecological effects.

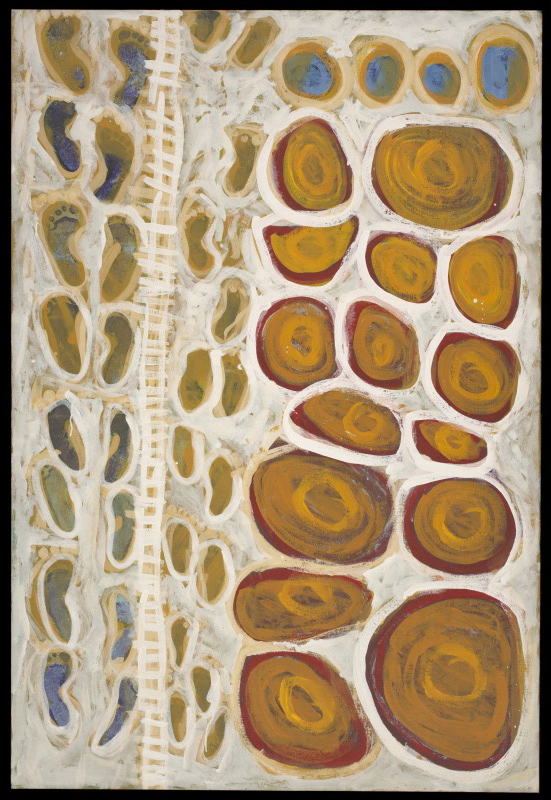

Fences, as markers of private property across which human access is legally restricted, inhibited local Aboriginal peoples from maintaining traditional interactions held over thousands of years with their ancestral lands. Travelling alongside the rabbit-proof fence-lines was prohibited (it remains so along the current State Barrier Fence). One artwork from the Museum’s collection, however, illustrates an instance when fencing assisted, rather than disrupted, family connections. Footprints on the Rabbit Proof Fence by Judith Samson tells the story of two young Martu girls who, seeking to rejoin their family, journeyed along Western Australia’s No.2 Rabbit Proof Fence in 1931. This journey also features in the book Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence by Doris Pilkington Garimara (1996) and the film Rabbit Proof Fence directed by Philip Noyce (2002).

More recently, long-line animal barrier fencing in Western Australia (incorporating sections of the original rabbit-proof fence-lines) has prompted discussion and research in relation to its impact on native wildlife migrations. With some sections in place for over 100 years, the influence of rabbit-proof fence-lines on surrounding land use and vegetation patterns has also assisted researchers seeking to study the impact of land use on regional climates.

Links and further reading

Broomhall, F. H. The Longest Fence in the World: A History of the No.1 Rabbit Proof Fence From Its Beginning Until Recent Times, Hesperion Press, Western Australia, 1991

Coman, Brian Tooth & Nail: The Story of the Rabbit in Australia, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 1999

Crawford, J.S. History of the State Vermin Barrier Fences (Formerly known as Rabbit Proof Fences, Agriculture Protection Board (Western Australia), Perth, 1968

Murchison Regional Vermin Council

Rolls, Eric C. They All Ran Wild: The Story of Pests on the Land in Australia, Angus & Robertson, Australia, 1969

Rabbits in Australia – collections and stories at the National Museum

This post was co-developed by Jono Lineen and other curators at the National Museum of Australia.

I have a photo of my Grandfather Gustave K Smith on his camel drawn cart arriving back in Yalgoo after many weeks out patrolling the fence. He was based at Yalgoo from 1915 until about1931.He took on the job as a sub- inspector after he retired from farming aged 62 years

That sounds like an interesting photo Gustave. Any chance we could see it? And did your grandfather tell any tales of his time patrolling the fence? Best wishes, George.

Whilst researching my family Rodier, I noted the photo of Mr Rodier on his sulky inspecting the rabbit fence at Tambur WA? 1905. This is the same photo as Mr William Rodier inspecting……near Bourke NSW. Can you verify the location? WA or NSW?

Hello Rochelle, the catalogue record for this image states it is in NSW, please see the link below. Best wishes, George.

https://primo-slnsw.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=ADLIB110307401&context=L&vid=SLNSW&lang=en_US&search_scope=EEA&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=default_tab&query=creator,exact,Leaney,%20W.,AND&sortby=rank&mode=advanced&offset=0