Charles Ulm pilots ‘Faith in Australia’: Wakefield Oil and airmail

Charles Ulm and Charles Kingsford Smith ended their partnership after the final closure of Australian National Airways in 1933. Both men continued to promote the future possibilities of air services in separate ventures. Ulm purchased ANA’s ‘Southern Moon’ aircraft, rebuilding it and renaming it ‘Faith in Australia’, with a view to securing new airmail contracts. In 1933, he piloted ‘Faith in Australia’ from Sydney, with GU ‘Scotty’ Allan and PG ‘Bill’ Taylor as crew, with the intention of flying around the world.

‘Faith in Australia’, VH-UXX, was fitted with new fuel tanks to provide a longer flight range. Ulm also had new Wright Whirlwind engines installed, tried and trusted in his eyes after the ‘Southern Cross’ flights. With the fit-out, testing and flight plans complete, ‘Faith in Australia’ and crew began their journey England on 21 June 1933.

Despite extensive preparations, engine troubles and inadequate landing grounds plagued the flight. The fuel pump had to be replaced in Derby, the aircraft was bogged on the aerodrome at Yangon (then Rangoon), Myanmar, and a complete overhaul of the engines was required at Jask, Iran. Short hops were then required to keep the engines from overheating for the rest of the flight to England, via Aleppo, Rome and Orange in France.

Their time in England was brief as Ulm, Allan and Taylor made their plans for the next stage of their world flight, across the Atlantic Ocean. They decided to fly to Ireland and start their Atlantic crossing from Portmarnock Beach, north of Dublin, as Kingsford Smith had done in the ‘Southern Cross’ in 1930. Disaster struck when ‘Faith in Australia’ sunk into the sand as it took on its full load of 5000 litres of fuel. The starboard undercarriage cracked with the weight, also damaging the starboard propeller and wingtip as it sunk. [1]

Several of the Irish police officers guarding the aircraft were injured and taken to hospital, while the remainder assisted in unloading and attempting to rescue ‘Faith in Australia’ from the beach and the rising tide. The salvage could not be completed until the following day, when the Irish air force assisted, and a full assessment of the damage was made.

Rescued by the Patron Saint of Aviation

The crew had used all of their resources on the flight thus far, and they were left stranded in Ireland without the funds to repair their ‘Faith in Australia’. Their hopes in continuing the journey had sunk with their aircraft. As they contemplated their limited options, Ulm received a telegram from Lord Charles Wakefield, offering to cover the costs of repairing ‘Faith in Australia’. Ulm accepted the generous offer, and began work immediately, shipping the aircraft to the Avro works in Manchester.

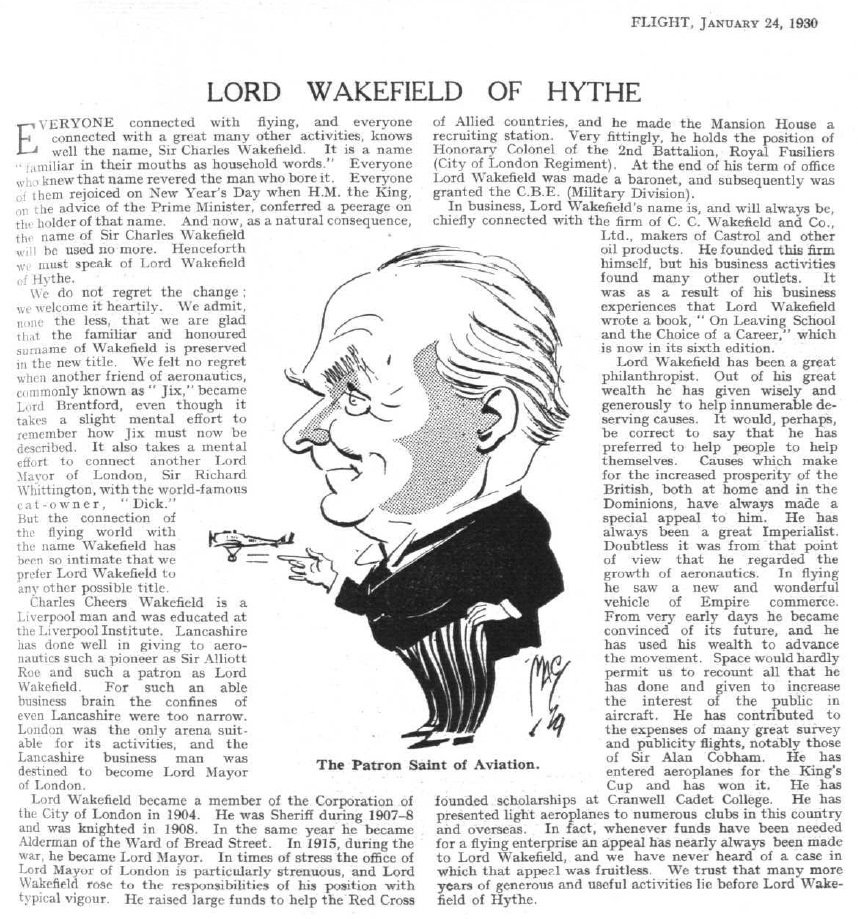

Wakefield was no stranger to Ulm or Australian aviation. Charles ‘Cheers’ Wakefield (1859-1941) had established the Wakefield Oil Company in 1899 when he left a job at Vacuum Oil to start his own business in London, selling lubricants for trains and heavy machinery. [2] He took a strong interest in automobiles and aircraft, and Wakefield worked with his company researchers to develop a lubricant capable of meeting the needs of the new engines. Registered in 1909, the result was measures of castor oil and vegetable oil made from castor beans, leading the new product to be called ‘Castrol’. CC Wakefield and Company Ltd began marketing its Castrol lubricants in Australia in 1913.

Through his company’s success, Wakefield supported numerous flights across the world, including the first England-Australia flight of 1919 and Bert Hinkler’s solo England-Australia flight in 1927. When Ulm and Kingsford Smith landed in Australia after their successful trans-Pacific flight, Wakefield sent congratulations: “Courageously conceived, intrepidly completed, combining sheer pluck and efficiency.” [3] In Australia, aviators owed much to Wakefield’s Australasian manager Cyril Westcott for the attentions of their patron.

Wakefield also turned that patronage to his own advantage, using the details of the flights he sponsored, many of them pioneering and record-breaking, and the names of the aviators in Castrol advertising. He sponsored aviation events and races, and the Castrol logo was painted on each aircraft fuselage for effective product exposure.

In Charles Ulm, Wakefield found a grateful client, who was himself especially adept at securing sponsorship. Ulm recognised sponsorship as an integral part of getting any aviation venture off the ground. It was his skills of persuasion that had secured support from Vacuum Oil, the Sun, the Melbourne Herald and the Brisbane Daily Mail newspapers for his and Smithy’s flight around Australia in 1927, which in turn laid the groundwork for their trans-Pacific flight in 1928.

Despite Wakefield’s assistance, continuing bad weather forced Ulm to abandon his trans-Atlantic flight and begin his plans to fly back to Australia. When Kingsford Smith set a new record flying from England to Australia in Miss Southern Cross, Ulm, Taylor and Allan decided to fly home and attempt to break the new record.

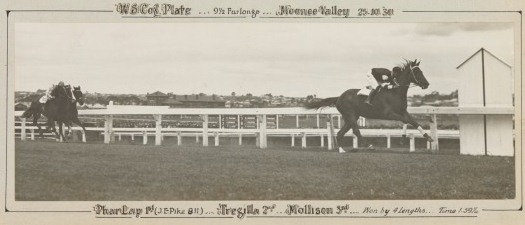

On 13 October 1933, the men left Feltham aerodrome, near London, and flew to Australia via Athens, Baghdad, Karachi, Calcutta, Sittwe (Akyab), Alor Setar (Alor Star) and Surabaya. Faith in Australia landed at Derby, Western Australia, on 19 October, completing the England-Australia flight in a new record time of 6 days, 17 hours and 56 minutes, beating Smithy by about 11 hours. They, of course, used Castrol motor oil, and Ulm strengthened his association with Wakefield.

Trans-Tasman airmail

Back in Australia, Ulm turned his attentions to airmail services. He hoped that his successful England-Australia flight would convince the government to back a wholly Australian-owned company to operate the Australia-Singapore link of the Australia-England airmail service, and of course back his own tender for that service.

To further his claim, on 3 to 4 December 1933 Ulm piloted ‘Faith in Australia’ from Richmond aerodrome in New South Wales to New Plymouth, New Zealand. Ulm and his crew – George Urquhart ‘Scotty’ Allan and Rupert ‘Bob’ Boulton – were accompanied by Ulm’s wife Jo and secretary Ellen Rogers. On arrival in New Plymouth, they became the first women to fly across the Tasman sea.

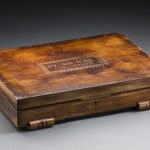

Amongst the small collection of airmail that Ulm carried to New Zealand was this commemorative box, presented by Roslyn Foster Bowie Philp to Lord Charles Wakefield. The box, which carried 25 flight covers addressed to Wakefield Castrol Oil Products market distributors, has now returned to Australia, purchased by the National Museum in 2014.

The hinged box lid has an impression of an airmail stamp, reading ‘BY AIR MAIL/PAR AVION/SPECIAL AIR MAIL DEC 1933’. An engraved metal commemorative plaque, attached to the underside of the lid, conveys flight and presentation details, and inside the box is a special ‘by air mail’ cavity. Much heavier than the usual airmail bags, the box was an unusual flight souvenir, held in the Wakefield collection until Castrol was purchased by BP in 2000 and it was sold to a private collector.

The current display of the airmail box in the National Museum’s new acquisitions case highlights the key role played by oil companies in product supply and also sponsorship for Australia’s early aviation ventures.

Oil and Australian aviation – the past and the future

The main link between oil and aviation is obvious, motorised aircraft need fuel and engine lubricants to fly. However, most of us think of aviation fuel and lubricants only if we happen to catch a glimpse of a maintenance crew, or on hearing the announcement “Please turn your mobile phone off when exiting the aircraft and crossing the tarmac as the aircraft is being refueled”.

When aviation was still finding its way during the 1920s and 30s, pioneering flights were an opportunity for oil companies to test and promote their products, and a good product assisted aviators in completing their journeys. The Vacuum Oil Company, starting business in Australian in 1895, was the first oil company in Australia to appoint an aviation manager in 1913. Shell also established itself in Australia during the late 1890s, supporting many early aviation ventures by ensuring that supplies of its products in central and isolated locations for aviators across the world. Atlantic Union Oil Company arrived in Australia during the late 1920s, and by supplying Ulm and Kingsford Smith’s trans-Pacific flight in 1928, found ample advertising opportunities.

Today, aviation companies are more concerned with carbon emissions, fuel efficiency and developing sustainable biofuel. Virgin Australia states, “98% of our emissions footprint is the result of aircraft fuel burn”. [4] Leading Australian commercial carriers Qantas and Virgin introduced carbon offsetting in 2007, inviting passengers to neutralise the carbon emissions from their flight. Qantas states that “more than two million tonnes of carbon emissions – the equivalent of planting 12 million trees – have been offset since Qantas and Jetstar introduced offsetting in 2007”. [5]

Between 2000 and 2009, the number of passengers carried on flights in Australia and New Zealand grew by 60 per cent, with 32 million people carried on international flights and 51 million on domestic flights, indicating the central role of aviation in transport and tourism. [6] The global aviation industry is aiming to achieve carbon neutral growth from 2020 and 50 per cent reduction from 2005 levels by 2050. The development of more efficient aircraft and engines has assisted, but it is understood that the only way to meet these targets will be the use of alternate fuels that meet all of the environmental, economic and technical challenges. Sustainable aviation fuel derived from biomass (non-food parts of crops, plants, trees, algae, waste and other organic matter), or bio-fuel, is now a focus for aviation companies to ensure their futures.

As aviation companies explore the best ways to meet these challenges, a new generation of pioneering flights are being made. The Solar Impulse project, while not necessarily demonstrating an exact future for aviation, has drawn attention to the potential of clean technologies, with founder Bertrand Piccard stating, “The only way to motivate people is to demonstrate the existence of solutions, not only to speak about the problem”.

[1] Ellen Rogers, Faith in Australia: Charles Ulm and Australian aviation, Crows Nest, NSW; Book Production Services, 1987.

[2] Castrol corporate history.

[3] Daily News, Perth, 9 June 1928, p7.

[4] Virgin Australia sustainability statements.

[5] Qantas media release, 5 June 2015.

[6] CSIRO, ‘Sustainable Aviation Fuel Road Map‘

Ulm’s RAAF uniform cane and the commemorative airmail box, from Ulm’s flight to New Zealand in December 1933, are on display in the Museum’s new acquisitions showcase until 23 August 2015.

For more information: www.nma.gov.au/collection/highlights/aviation

Feature image: ‘Faith in Australia’ after the accident on Portmarnock Beach. With the tide advancing, Irish Police attempt to lift and move the damaged aircraft, 26 July 1933. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.