Seeing seaweed

I’ve never really been all that keen on seaweed. At least, not until recently, when a nineteenth century album of pressed seaweed specimens began to open my eyes to the wonderful world of marine macroalgae. Now I find seaweed changing how I see and think about Australia.

I grew up in an inland city and for much of my life my encounters with seaweed have been limited to moments during annual coastal holidays when, bobbing around in the ocean, I suddenly felt slippery brown tendrils wrapping themselves alarmingly around my legs, or, walking along the beach, I was assailed by the acrid odour of a pile of decaying vegetable matter. Sure, I’ve spent a fair amount of time poking around in rock pools and even diving into deeper waters, but like a lot of people I was mostly attracted to marine creatures who travelled, like fish and crabs, or who at least, like anemones, responded to my touch. Seaweeds and other marine plants were always there as a kind of theatrical backdrop, but I don’t think I ever truly looked at them.

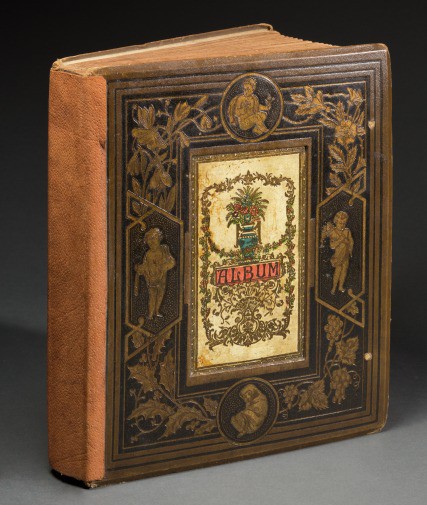

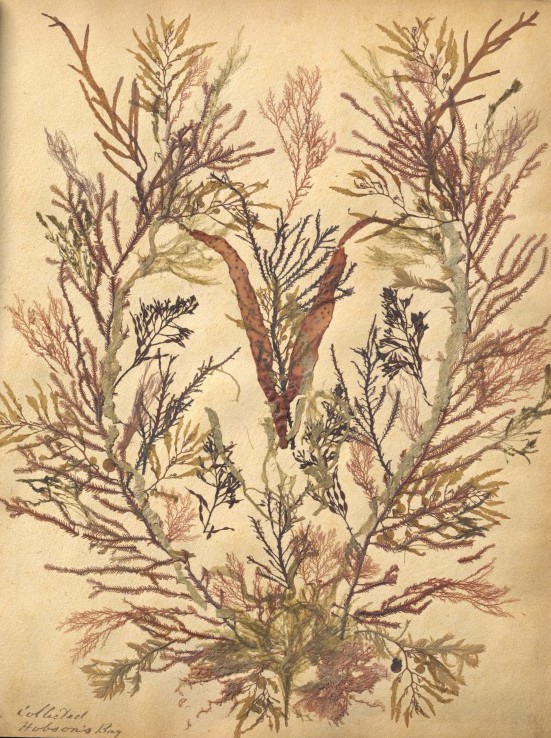

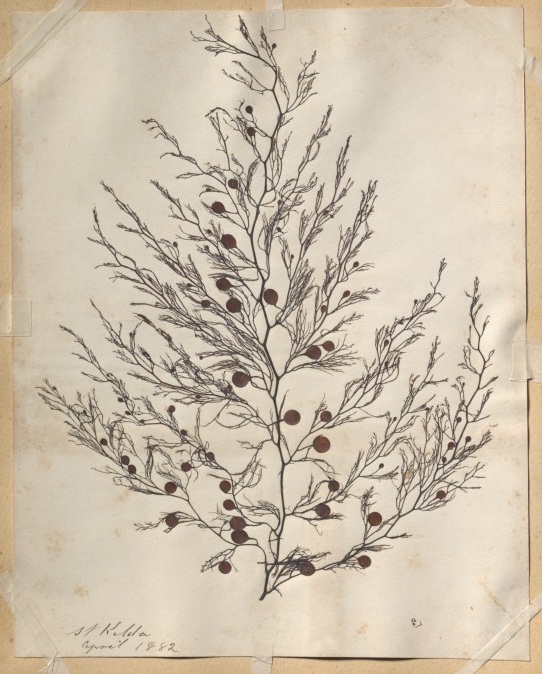

Then, a few years ago, the National Museum purchased an album containing over 200 specimens of pressed seaweeds, as well as a few zoophytes, mosses and ferns. It’s a striking but somewhat mysterious object. Hand-written annotations on the seaweed specimens indicate that most of them were collected between the 1850s and the 1880s in Port Phillip Bay, around which the city of Melbourne now spreads, at places like St Kilda, Hobsons Bay, Sandridge (now Port Melbourne), Brighton and Queens Cliff (now usually Queenscliff). One, collected in 1851, comes from the north of Ireland, and two, collected 1854, come from the Cape of Good Hope, hinting that the album’s creator migrated from Great Britain to Melbourne in the mid-nineteenth century, perhaps lured by the gold fever of the time.

The album is not really a conventional nineteenth century natural history object. Unlike a fully elaborated scientific collection, only some of the specimens are annotated with their dates and places of collection or their Latin genus and species names. The collector doesn’t seem to have been particularly interested in acquiring a wide range of species, often pressing the same type of seaweed over and over again. The album also isn’t recognizably an artwork, unlike some other surviving nineteenth century seaweed collages. In the first few pages, the maker has created a decorative and picturesque display of seaweed fronds but in the rest of the album the focus is on simply fitting as many specimens as possible on to each page. To further complicate matters, in some places the seaweeds have been stuck directly to the album’s leaves, while in others specimens on loose paper have been fixed with paper tabs, arranged without any apparent order relating to date or place of collection. It doesn’t feel like the album was even created as a souvenir of successive seaside holidays.

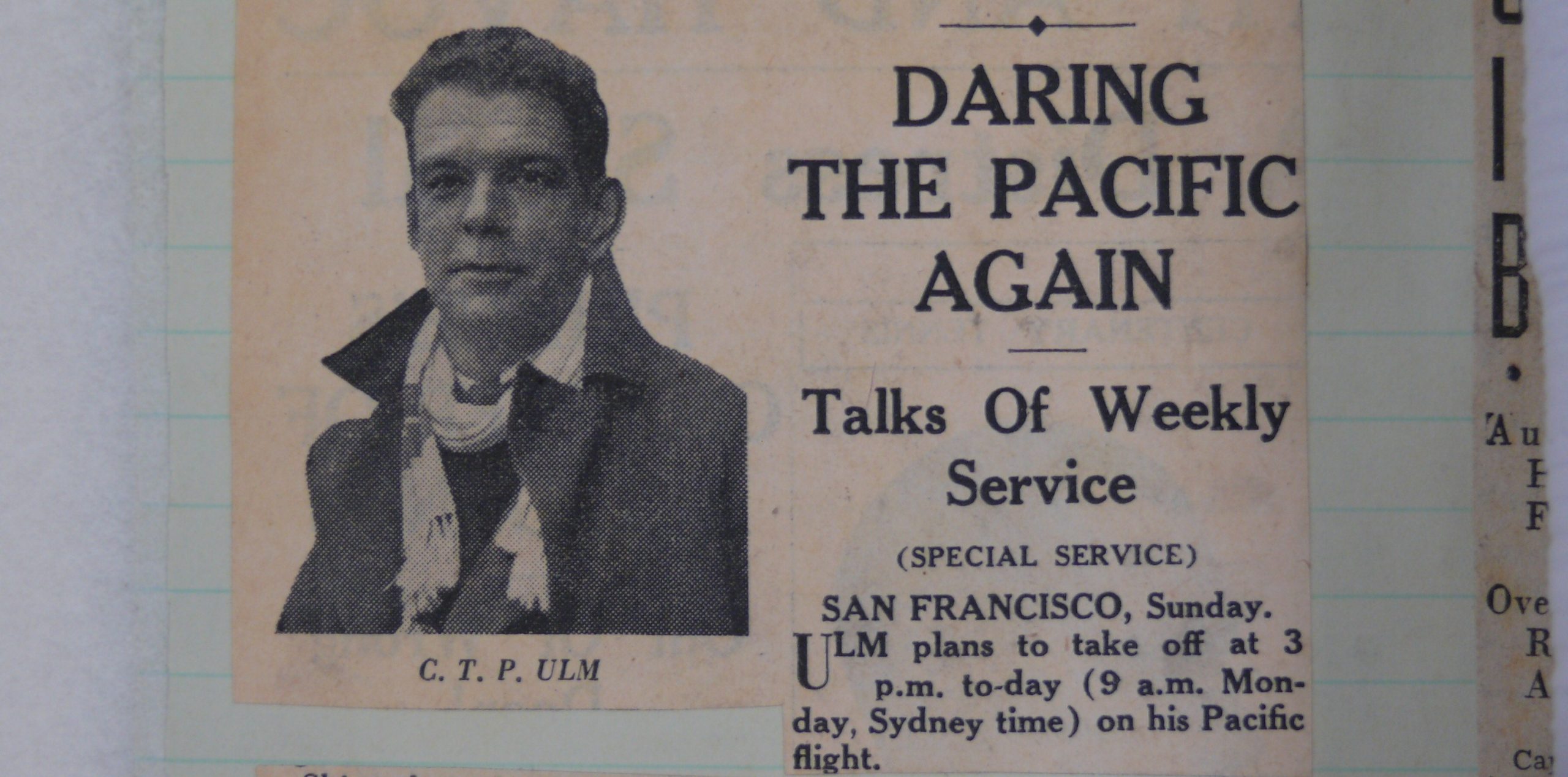

It turns out that at the time the Port Phillip album was created there was a thriving community of Australians fascinated by seaweed. Mid-nineteenth century newspapers include letters advocating for the development of an industry turning seaweed into fertiliser, advertisements for mattresses stuffed with dried seaweed and accounts of shipwrecks that note ‘banks’ of seaweed as an obstruction to rescue efforts or describe seaweed as sombre emblems of the drowned. At the same time that these industrial and sentimental meanings of seaweed were circulating, local interest in phycology (the scientific study of algae) was flourishing, with Australian enthusiasts enlivened by the eminent Irish phycologist W.H. Harvey’s collecting tour along the southern coast of the continent in 1854-6, and the publication in 1862 of his Phycologia Australica. As the science of marine algae flourished, so too did interest in these plants as intriguing, aesthetic materials. Seaweeds were christened the ‘flowers of the sea’, wealthy homeowners purchased household items decorated with algal motifs, and artists created elaborate seaweed ‘pictures’ and specimen albums, some of which were good enough for inclusion in international exhibitions.

Over the next few months, I’ll be trying to learn more about how the National Museum’s Port Phillip seaweed album illuminates and expands our knowledge of these complex, inter-twined meanings of seaweed. In order to facilitate this research, National Museum photographer George Serras, senior conservator Tania Riviere, and I, recently spent a day creating images of the object. As ever when working with George, I was struck by the interpretive and creative nature of this ‘documentation’ process, as decisions about what kind of photographs to take, and how to take them, emerged through our shared conversations about the ways in which we each see the object, what we know about its history, what it communicates to us and what aspects we would like to draw to other people’s attention. Of course, we also needed to consider how we could photograph the object without jeapordising its safety.

For the Port Phillip album, George developed an approach that would give the feel of natural lighting, while also capturing the three-dimensionality of each page. When you look closely at each page of the album, you notice the different colours and shapes of each specimen, the breadth, depth, branching and edging of their fronds or blades, the size and roundness of their floats, their degree of translucency and the folds and twists created in pressing. Some specimens include only fronds or parts of fronds. In others, an entire plant, including the holdfast, by which the seaweed anchors itself, have been captured. Others have tiny fragments of other kinds of seaweed, or bubbles of sand, or bits of coral and rock trapped in their fronds. For me, these details resonate and remind us of the living plant, referencing its removal from the sea, and inviting us to jump from the fragment held static in the album to imagined fields of supple, sinuous fronds waving in ocean flows.

In order to capture these details, George chose to light the album with a single dish reflector that would produce a slightly harsh light with soft shadows. This technique helped accentuate the textures of the specimens and other three-dimensional elements of the album, without creating the flattening and double shadows of traditional copywork lighting. The light was placed at around 45 degrees from the top left of each page to allow for shadows to fall naturally, as if the light source was the sun. This approach meant, however, that each page was lit strongly in one corner, with the light fading across the page. To overcome this problem, George used Capture1 software to analyse the light source and even out the light across the whole page. George also focused strongly on ensuring that the diverse colours of the seaweed specimens were recorded accurately. In initial captures, he used the Grateg MacBeth colour chart to determine accurate exposure and create a colour profile, and then ‘applied’ this profile to each of the photographed pages to create colour corrected digital files.

My day spent with George and Tania photographing the seaweed album reminded me that, although I’m keen to understand more about its life over time, I also don’t want to forget the experience of first encountering the album. When I research an object’s history, it’s sometimes easy to get caught up in the mystery of its creation and use, to let the quest to describe its story overwhelm my responsiveness to its ability to move me to new ways of looking at and relating to the world around me. When I first saw images of the seaweed album, on offer in an antique book dealer’s catalogue, I was struck by the intricate beauty of the seaweed forms. They were other-worldly and yet somehow also instantly recognizable as my companions on this planet. When I came to look at the album itself, I felt that I had suddenly seen seaweed for the first time.

As I spend more time with the album, and think about its strange, unique character, I’m beginning to think that this experience of complicated wonder might also have motivated its creator. Perhaps she or he made the album, and the specimens it holds, for the simple pleasure of appreciating seaweed, for the feeling of its strange, wet sleekness and the shape of its varied, intricate forms. Perhaps this explains the peculiar, slightly obsessive nature of the album, its refusal to adopt the conventional mid-Victorian practices of either art or science.

Early this morning I listened to a ABC Radio National radio interview about how, as climate change warms and run-off pollutes our oceans, Australia is losing its forests of giant kelp, perhaps the most iconic of seaweeds. Up to 95% have already gone. Surely there is no more important time to attend to objects, like the Port Phillip seaweed album, that can help us connect with the ocean and the plants and animals that live in it.

You can learn more about the marine life of Port Phillip Bay here, and the endangered giant kelp marine forests here. If you have a seaweed story, please let me know in the comments box below.

[Feature image: Detail from the title page of the Port Phillip seaweed album. National Museum of Australia. Photograph by George Serras.]

Great post, thanks Kirsten. Interesting to think how a museum object like this seaweed album can both convey a sense of the love and fascination a person had for places and their biological communities, and encourage new connections that might help to secure a stable climate and flourishing oceans.

Interesting post; is the album available for viewing on the NMA web site?

Hi Techapilla. Thanks for your kind comment. Unfortunately, the album isn’t yet available on the Museum’s website, but we’re working on it! Cheers, Kirsten.