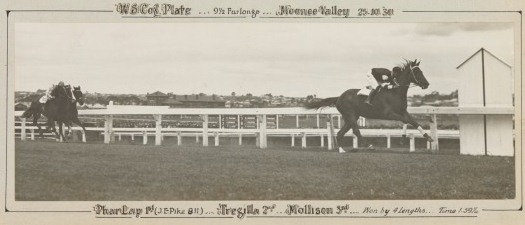

Phar Lap was a horse

Isa Menzies is a PhD candidate at the Australian National University, where she is examining how museums in Australia and New Zealand have interpreted horse remains, particularly in relation to narratives of national identity. Before becoming a student again, Isa spent almost a decade working in museums across a variety of roles, including as the curator responsible for Phar Lap’s heart at the National Museum of Australia.

In this guest blog, Isa reflects on the recent rediscovery of tissue cut long ago from the heart of Phar Lap, and the potential offered by these two containers of organ parts and preserving fluid to reimagine the great Australian race horse.

The name ‘Phar Lap’ conjures all sorts of imagery: the Melbourne Cup, perhaps, or the nobly-posed figure on display in the Melbourne Museum, or the abnormally large heart, which inspired the phrase ‘a heart as big as Phar Lap’s’. While the name evokes all those things and more, it is unlikely that when people think of Phar Lap, they will call to mind the yeasty scent of warm horse, or the nickering one might hear with the approach of the morning feed; the brief brush of whiskers as a muzzle investigates a hand for any hint of a treat; the stamp of a hoof, the whisk of a tail. In short, what people generally won’t think of, is Phar Lap’s essential horse-ness.

![Phar Lap with strapper Tommy Woodcock and other admirers, 1931. By Charles P S Boyer (http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23120509) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/phar-lap-and-tommy-woodcock-e1423019641216.jpg)

Animal studies scholars generally recognise that the alterity of the non-human animal is unknowable. We, as humans, are shaped by a particular subjectivity – standing upright upon two legs, the chemistry of our brains, and the senses we privilege – these all combine to determine how we view the world. The acknowledgement that this is not the only way that the world may be perceived is one of the key tenets of animal studies. To apply such an approach to interpreting Phar Lap in the museum context would be to reconfigure his equine subjectivity, and to make it central to any representation of him.

The current display of the missing sections of Phar Lap’s heart, until recently hidden in plain sight among other biological specimens in the National Museum of Australia’s climate-controlled storage space, attempts just that. These somewhat non-descript, fleshy relics are housed in two separate containers. In one, the sections taken from the ventricle wall, aorta, and pericardium are mounted in clear fluid; in the other, the portions of heart wall and aorta are surrounded by pieces of the pericardium, which appear to be billowing, frozen in perpetual chemical preservation. On show as part of the exhibition Spirited: Australia’s Horse Story, the parts are interpreted simultaneously as biological specimens, and remnants of the cultural icon that is Phar Lap.

While the label associated with one of the containers talks about the dissection and subsequent preservation of Phar Lap’s heart, the other tells the audience that a horse’s heart beats between 28 and 45 beats per minute, and a human heart beats at around 75 beats per minute. The blood vessels of a 450 kilogram horse carry around 34 litres of blood (according to the Red Cross, an adult human has between four-and-a-half and five litres of blood). This purely biological information allows us to compare the human body with that of a horse; it by-passes our cultural understanding of Phar Lap the icon, and reminds us that, first and foremost, he was a horse.

I have written elsewhere about the historification of the Phar Lap remains, which until recently comprised the mounted hide in Melbourne, the heart at the National Museum , and the skeleton at Te Papa Tongarewa, in New Zealand. Each of these, once an essential part of the complex biology of Phar Lap the horse, began its afterlife as something other than a historically significant object; yet each has found its way into a museum. Today, each of these objects is synonymous with the horse himself. Visitors do not request to see the heart of Phar Lap because it is an example of twentieth century preservation techniques, or even simply because it is unusually big. They want to see it because of Phar Lap, and because of what Phar Lap means.

Museology scholar Susan Pearce has drawn on semiotic frameworks to articulate the role that objects serve in meaning-making. Pearce argues that objects, like language, function as communication systems.[i] In the museum context, objects act as ‘symbols’, which in the semiotic sense means they represent a broader collective understanding. For example, Phar Lap’s heart is not simply a specimen of biology – an unusually large horse heart – but an object that visitors to the National Museum regard as significant, and specifically request to see. The heart does not so much represent the living horse, as the culturally ascribed meanings conjured by the words ‘Phar Lap’: hero, icon, big-hearted battler.

Museums have played an integral role in the transition of Phar Lap’s remains away from their particularity – whether as biological specimen, theatrical mount, or an example of 1930s taxidermy – and towards a more general association with the horse. They have also been the means through which the notion of Phar Lap as a historically significant figure has been established.[ii] The way that objects are interpreted (ie written about, displayed, promoted, and understood as important) by museums also shapes how they are perceived by audiences. Given the newly-discovered pieces of the heart do not have an eighty year-long public history, it is interesting to speculate as to how they might now be incorporated into the pantheon of Phar Lap’s Parts.

As rather unremarkable pieces of tissue, they do not easily allow us to project the afore-mentioned notions of who Phar Lap was onto them. They do not, for example, speak of a handsome chestnut gelding in the way the life-like pose of the taxidermied mount does, nor do they confirm our belief that Phar Lap (and subsequently Australians in general) are big-hearted (literally as well as metaphorically, in the horse’s case at least). They are not touchstone objects, they do not evoke glory. In reality, these carved out pieces of a horse heart are the somewhat awkward reminders of the evisceration of a national hero.

In writing about taxidermy, Dave Madden emphasises the viscerality of the process. His description reminds us that, in creating the physical legacies of Phar Lap so admired today, he would have been ‘gutted, his fat stripped away from the flesh, his brains pulled from the cranium, his eyes replaced by hard plastic’.[iii] Phar Lap’s organs – the heart that pumped his blood around racetracks, the stomach that digested his feed, the bowels that produced his excretions – were all removed for necropsy; finally, his bones would have been boiled, to strip them of flesh and cartilage, that they might later be mounted on wire and displayed. The processes by which Phar Lap was sculpted into a historical figure were also the processes by which he was divested of his status as a living, breathing animal. His horse-ness was stripped away with his flesh, and what now remains is a human re-construction of a horse named Phar Lap, which exists largely in symbolic terms.

Enter two containers of small, spongey, once-pink pieces of tissue, embalmed in preserving fluid. These two square jars represent a potential turning point for the way Phar Lap is understood, returning him from a mythologised figure to a flesh-and-blood horse. The visceral remains are undeniably uncomfortable; there is no easy way to reconcile their existence with the images of Phar Lap that we are familiar with – the Melbourne still-life in his glass case, or even the heart, whose fleshiness we are inured against after long exposure. As such, they disrupt the narrative of objectification that Phar Lap has been subjected to since his death. Particularly in their current context, where they are displayed among other specimens of equine biology in an exhibit that emphasises the physical difference between horse and human, the pieces of Phar Lap’s heart offer us an excellent opportunity to remember Phar Lap as a living creature once more.

![Phar Lap with jockey Jim Pike at Flemington racecourse, around 1930. Photograph by Charles Daniel Pratt, 1893-1968 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/phar_lap.jpg?w=560)

References:

[i] Pearce, Susan M. Museums, Objects and Collections: a cultural study. Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1992.

[ii] Menzies, Isa. “Phar Lap: from Racecourse to Reliquary.” ReCollections: A Journal of Museums and Collections 8 (2013).

[iii] Madden, Dave. The Authentic Animal: Inside the Odd and Obsessive World of Taxidermy. New York: St Martin’s Press, 2011: 8.

It is no coincidence that the Depression produced many sporting icons around the world, both human and animal.

Your post reminded me of ‘Mick the Miller’ (1926-1929), the fabulous Irish racing greyhound. Mick’s vital organs may not have been revered like Phar Lap’s, but he is memorialised in statues, sculptures and other works throughout Great Britain. His mounted skin, however, is on display at the Natural History Museum in London. Interestingly enough, he is in the household dog section!