Politics and water power

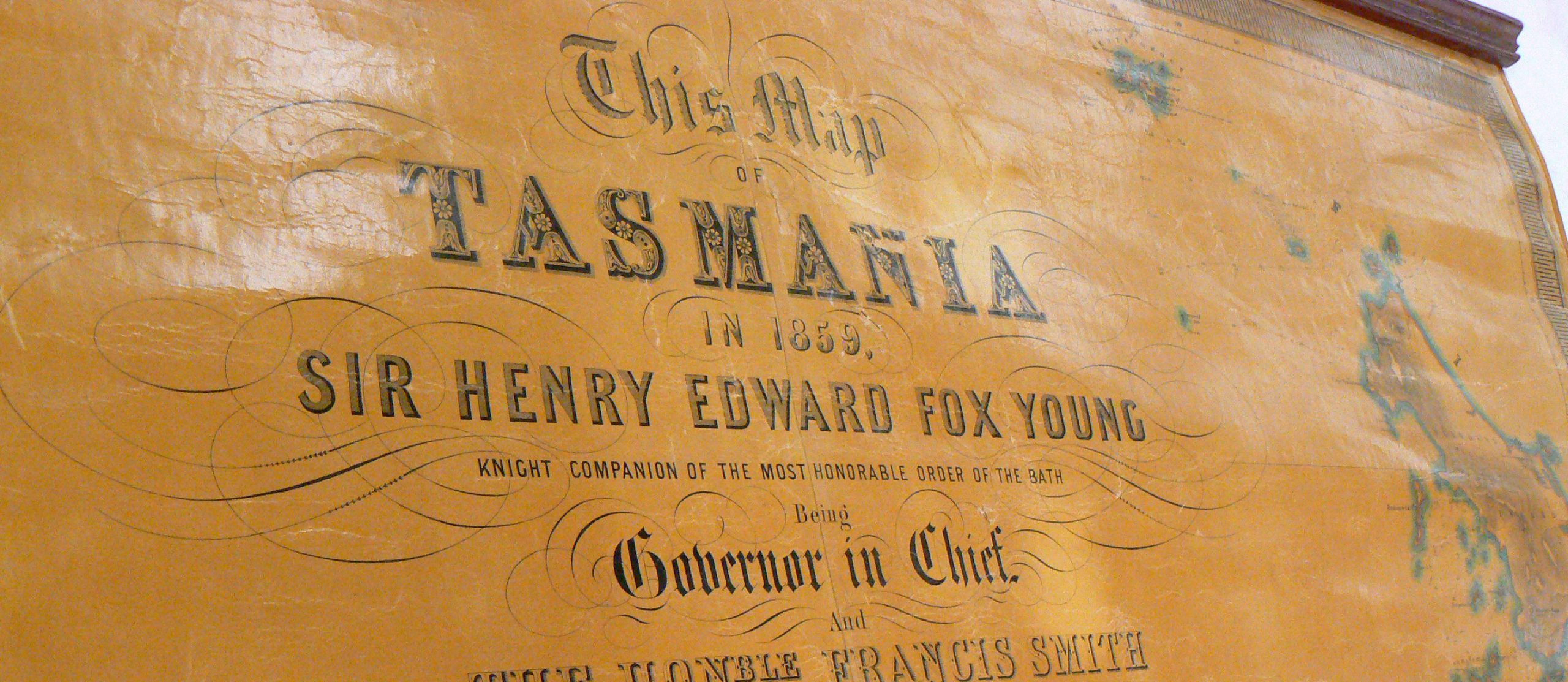

Recently, in one of those happy accidents of timing, I went on holiday to Tasmania where I was able to visit one of the places I had recently been researching. I have been working on some artefacts from Tasmania, all drawn from the Bob Brown collection. There are 3000 items in this very large collection, and it remains an ongoing challenge to decide which to choose.

Given that this collection is about political activism against the ongoing development of hydropower in the latter half of the twentieth century, part of the research necessarily includes establishing the historical context of hydroelectricity. I decided to find out, just as a quick starter, when the first hydroelectricity plant was developed. As so often happens with historical research, what seems like a simple question is not remotely simple.

This is not an uncommon experience in historical research. In particular, what piqued my interest as I went along was how certain ‘facts’ got consistently misrepresented. In this case, I’m going to dub it ‘the Edison factor’ although you could easily just call it ‘the celebrity factor’. I found that the most frequently repeated answer on popular websites to the question ‘when the first hydroelectricity plant was developed?’ is 1882, the Fox River in Appleton, Wisconsin, by Thomas Edison. While Thomas Edison was certainly pivotal in the history of power, he had nothing to do with this particular project. Rather, it was an employee of his who mentioned, while fishing with a friend, that Edison was planning a steam powered electric plant in New York City. The friend, the owner of the Appleton Paper Mill, decided to experiment with Edison’s system but using the water of the Fox River. In this, he was like many of the other businessmen, industrialists and entrepreneurs who rapidly deployed Edison’s inventions in their own sphere of the world.

The unequivocal first use of hydroelectric power occurred two years before Fox River. Meet Lord William Armstrong, who in 1880 successfully lit his house at Cragside in Northumberland using hydroelectricity. Lord Armstrong was every bit as interesting and charismatic as Edison, and if you’d like to read more about Lord Armstrong and his National Trust listed house, click here. http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/cragside/

The next major development in the use of hydroelectricity was for industrial purposes, when the Wolverine Chair Company of Grand Rapids, Michigan ran lamps. Back to England, the next major development was for municipal purposes when in 1881, the village of Godalming in Surrey experimented with hydroelectricity to run streetlights.

So what about Australia? The first two attempts at using hydroelectricity both happened in 1888, under remarkably different situations. One was to improve the experience of visitors at the Jenolan Caves, while in northern Tasmania, the still operating Waverley Woollen Mill installed the first commercial hydro power plant. The Launceston Examiner reported the Mill’s ‘open night’ in detail, including the hope that ‘that our go ahead Mayor and aldermen would make use of the magnificent water power at their disposal and introduce electric light all over the town of Launceston’.

Follow up reports in the paper show how interested other towns and organisations were in the Waverley Mills experiment. Launceston itself embarked on a long and highly controversial process of hydroelectric development, which lead in 1895 to the first publicly-owned hydro-electric plant in the Southern Hemisphere at Duck Reach on Cataract Gorge.

It seems slightly ironic to me that Bob Brown, the man who shot to fame for spear heading the campaign against the proposed Franklin dam, should have migrated to the place where commercial hydropower began in Australia. Compared to the exhaustive amount of coverage of the technical aspects during its construction, the reception to the successful first trial was remarkably brief. The Launceston Examiner wrote ‘The trial was very successful, and was much commented upon during the evening’, and then went onto recap the scheme’s long and difficult political history. It would seem that hydroelectricity in Tasmania has an interesting history of debate and counter debate, well before the celebrated Franklin Dam campaign.