Not all horse play

Nowadays when you talk about a ‘work horse’, you are probably referring to a ute, truck or some other form of mechanised equipment. In the not too distant past, a work horse was, as the phrase suggests, a heavy horse used for work and most likely for haulage. In many museums (including the National Museum) you can view displays of machinery that these horses hauled or powered. Rarely, however, do you see or think about the objects that helped to power the horses.

Working horses set the rhythm of the day for many people in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. On rural properties, for example, farmers typically rose before dawn to feed and harness draught horses before the working day began. After a morning of hauling a plough, harrow or other horse drawn machinery, a break was needed to spell the horses, give them feed and water and, if needed, change the team. At the end of the day the horses would again be cared for first. They were unharnessed, watered, groomed, and ailments tended to, before being turned out for the evening.

Fuelling horses remains a crucial aspect of using horse power; horses need to be given enough time to digest their food and be fed regularly in order to maintain their condition and productivity. Recently at the Museum we were excited to locate a horse feed trough for the National Historical Collection. The trough is enormous, constructed from a hollowed out tree log and is still located on the original wheat and sheep property near Yeoval in the Central West of New South Wales.

While the horses are now gone, the property ‘Norwood’, continues to be farmed by the Wykes family. Fortunately, this provides an opportunity for the museum to document the trough more fully in the context of the history of the working property. On ‘Norwood’, there remains considerable evidence of its past as a horse powered property: a blacksmiths forge, a chaff shed, a dam used to water the horses and the ‘grass paddocks’ used to house them. Until the stable building recently deteriorated, the trough sat on wooden blocks against the stable wall where they had stood for about a century.

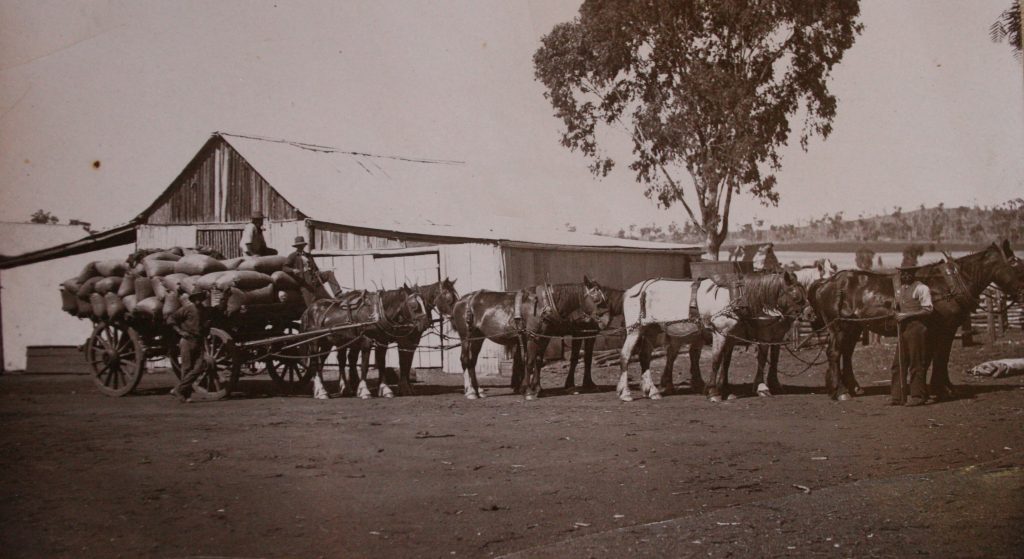

Last week myself and fellow curator, Jennifer Wilson, traveled to ‘Norwood’ to gather as much information as possible about the history of the trough, the property, and the people and horses that worked the farm. We were lucky to be able chat with members of the Wykes family about the property, examine the documentary and built heritage relating to horses, and assess the logistics of moving the trough. In our conversation with Desmond and Laurel Wykes and Leila Rigg, it became clear that the transition from a horse powered property to one powered by machines was not swift. Long after a tractor replaced the draught team, they recalled that two draught horses remained on the property. Horses were used in the family’s sulky and buggy for short trips even after the purchase of a motor car. As children, Des and his siblings rode horses to school (they were much better suited to the rough roads than bicycles) and competed in riding and racing events at the local show. Among old documents from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century kept by the family are numerous pointers to the importance of horses to the operation of the property: the purchase of harness, repairs to horse drawn agricultural machinery, and insurance policies for the chaff in the shed. Likewise photographs show the horse team harnessed to haul a load of wheat about to be transported to the rail head at Wellington and the mob gathered around the dam, presumably after a long day of work.

Jen and I were also given a tour of the property. At the far end of the farm are the horse paddocks still sheltered by large stands of White Box trees. The area remains uncultivated and in the Wykes family they are known as ‘grass paddocks’ because of the native grasses. While in easy walking distance to where the ‘Norwood’ house had stood, is the dam, forge, remnant horse drawn machinery and the chaff shed.

The trough itself is an example of farming craft that was once ubiquitous but now scarce. As farmers turned to mechanised forms of power, hand crafted items like wooden troughs were typically left to rot or burnt as firewood. Des and Leila believe that their grandfather Henry James Wykes constructed the trough in about 1900.

The trough is almost certainly made from White Box and, because of its size and weight, the tree probably grew a short distance away from where it was later used as a feed trough. Ron Edwards notes of the practice, that such troughs were usually fashioned from logs that had been already hollowed out from fire or ants. The Wykes trough has a somewhat blackened interior suggesting that fire aided its transformation from log to trough. To finish the job planks were simply nailed across the ends and trimmed to shape. The Wykes trough (one of two) measures over 4 metres in length, has a girth of over 2 metres and is estimated to weigh in the order of 600-700 kilograms. Chaff can still be seen in the crevices of the trough. And, if you look closely at one side, there are ‘V’ shaped patches of wear at regular intervals that probably indicate where each of the draught horses brushed against the trough while they ate.

The trough and its story will be a part of our Horses in Australia exhibition opening in September. As for moving the trough, our Registration team (responsible for coordinating the relocation) will be pleased to learn that the path to the trough is a well made track with no overhanging branches. Perhaps ironically, however, we will have to rely on a modern ‘work horse’- a tractor with front end loader – to move the trough on to the truck.

Do you have a ‘work horse’ story? We’d love to hear them … be they equine or mechanised!

[Feature Image: Henry James Wykes’ team in front of the shearing shed at ‘Norwood’. Photo courtesy of Desmond and Laurel Wykes.]

Beautiful story of the horse and horse trough!

I would like to hear more from you and i am saving your site so that i could visit it again soon! 🙂