The reef

How do we imagine the Great Barrier Reef? Does how we see this amazing marine environment decide whether or how we care for it?

The Great Barrier Reef stretches along the Queensland coast for over 3,000 kilometres, an intricate ecosystem including hundreds of kinds of corals, sponges, molluscs, rays, fish, birds, turtles, whales, dugongs, dolphins, plants, microscopic organisms, sea-water flows, sunshine and, of course, people.

Tourist brochures sing the reef’s praises as one of the seven wonders of the natural world, Earth’s largest coral environment and the only living system visible from space. And, for me, as an Australian of south-eastern attachments, and inland ones at that, it is the tourist industry’s standard promotional fodder that has shaped my sense of the reef. Like many Australians, I’ve never visited its underwater gardens, or at least have experienced only a fleeting encounter. I know the reef through impossibly brilliant colour photographs like the stunning image above and it’s always seemed a rather distant and abstract place of self-evident but rather unreal beauty.

Over the last few weeks, however, the reef and particularly its corals have jumped into my consciousness, asking me to look beyond the familiar glossy images to consider how we might know, and care about, rather than just imagine, the Great Barrier Reef.

I had the pleasure recently of attending the Sydney launch of historian Iain McCalman’s new book, The Reef: A passionate history. This wonderfully written and realised book, just published by Viking, explores the cultural- environmental history of this ecosystem. It narrates twelve stories of engagements between people, places, ideas and biosystems, considering how each has shaped our understanding of the reef. And it is a tale to tell, beginning with early British navigators like James Cook and Matthew Flinders experiencing a wreck-creating labyrinth that threatened disaster and death, and concluding with our developing sense of a fragile and embattled global treasure. You can learn more about The Reef: A passionate history here and find purchase details (rrp $49.95) here.

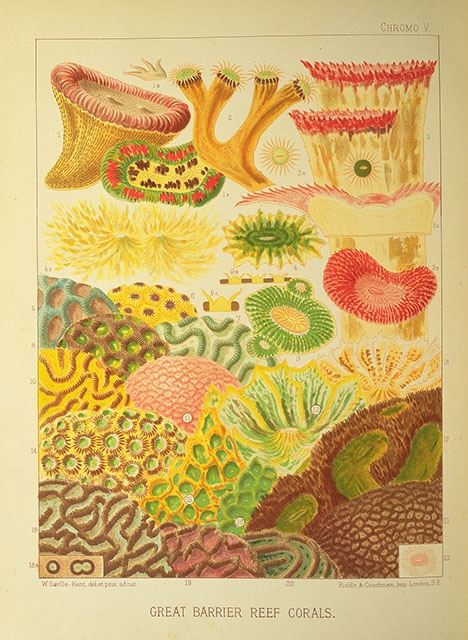

Two of the ‘characters’ in Iain’s narrative resonated particularly with me. William Saville-Kent arrived on the Great Barrier Reef in the late 1880s to survey the Queensland government’s oyster sites, and after spending his spare time on the reef indulging his passion for natural history, he fell, as Iain writes, ‘instantly and permanently in love with the wondrous marine world’. Saville-Kent became the Great Barrier Reef’s first scientist, a pioneering coral photographer and the first European-Australian to celebrate the reef’s astonishing beauty and diversity.

I first encountered Saville-Kent’s work some years ago, in the National Museum’s Rare Books collection, while researching a proposal for an exhibition about the history of Australian photography. I didn’t then know very much about the man but I still vividly remember opening his The Great Barrier Reef of Australia: Its products and potentialities and discovering his hand-drawn and hand-coloured chromolithographic plates of corals and fishes. At the time, I responded to these stunning images as the forerunners of the modern photographs that had created my sense of the reef, and in a sense they are. But it now troubles me to reflect on how easily I allowed them to reinforce my ‘understanding’ of the reef as a pristine natural wonder, a place spectacular but also foreign, a place other to me and my world, a place untroubled by human lives.

The source of this disquiet is coral scientist Charlie Veron, another of the people Iain McCalman introduces in The Reef. Veron, nicknamed ‘Charlie’ after Charles Darwin, began working on the Great Barrier Reef in the early 1970s. He became the foundation coral scientist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science and through thousands of hours of diving on the reef transformed our understanding of coral taxonomy, ecology and evolution. He also became a passionate advocate for reef conservation, witness to the contemporary devastation of coral ecosystems caued by sea levels changes, shifts in water temperatures, increased numbers of the predatory crown-of-thorns starfish and raised nutrient levels in the coastal oceans caused by agricultural run-off.

I met Veron at the Sydney launch of The Reef, and, searching around for a way to get the conversation going, asked him if he still managed to spend much time diving on his beloved reef. He replied that he was now very busy working on an online encyclopaedia of the world’s corals, and then he paused, and then quietly explained that these days he found it very difficult to go out to the reef because for him it was now always an experience of grief, of noticing how much of its grand diversity had already been lost. His words suddenly made my mental image of the reef, of blue waters, coloured corals and startling fish, starfish and anemones, seem almost horrifically naive and misled.

Two days later, I walked along the Sydney seashore, exploring the city’s annual Sculpture by the Sea exhibition. It seemed that the reef was inescapable, for I rounded a bend to discover a work called ‘Coral‘, an assemblage of painted plywood and polypropolene shapes interwoven to invoke a reef stretching over the coastal rocks. The artwork was produced by the Coral Collective, a group of artists, architects and academics, including Lindy Atkin and Steve Guthrie of Bark Lab (Bark Design Architects), Michael Dickson of the University of Queensland and Glen Cunnington of Humphrey Edwards architects, who had come together, as their catalogue entry explained, ‘in an extended dialogue about the nature of place and the process of making’.

I was delighted to see another group of Australians engaging with corals and working to ‘reflect on the beauty and collective nature of reefs’, as the catalogue continued. But in my elegaic mood, I was also moved to wonder whether this kind of human interpretation would, in the end, be all that is to left to us of the reef.

It seems to me that if we are to avoid this sad outcome, then we must think carefully and creatively about how we can represent, communicate and create new understandings of the Great Barrier Reef. How can we write a new chapter in our imagining of the reef? The tourist industry promotions that so informed my imagining of the place can help us appreciate its beauties, but they now also seem almost irresponsible. They present the reef as a untouched paradise, secure in its other-worldliness, when in fact it has been profoundly changed by human activity and is in mortal danger. Yet images that show the corals loved by Saville-Kent and Veron as dead and bleached, devoid of sealife and covered in algal slime, also seem inadequate. They are strangely disempowering, invoking again a sense of sepration, but this time tinged with hopelessness.

The challenge, I think, is to find a way to show the reef as inter-connected with people, not only with those who have lived and live now with its corals, sponges and turtles, but also with us landlubbers who may, for most of our lives, never swim above its many colours and strange forms. We need a new vision for the reef, one informed by a sense of shared connection with and care for this amazing environment. What might this look like?

Feature image: A Blue Starfish (Linckia laevigata) resting on hard Acropora coral. Lighthouse, Ribbon Reefs, Great Barrier Reef. Copyright © [2004] Richard Ling. Wikimedia Commons.

Reef story needs passion! Great blog Kirsten