Taking it to the limit – the ‘extreme’ sport of six-day bicycle racing

It’s difficult for us today to imagine a cycling competition where, as The Mercury (Hobart) reported on 17 February 1897, ‘exhausted riders [were] lifted from and on to their wheels and carried to and from their quarters, their joints swollen and inflamed, barely able to see, with wandering mind, and only kept in a conscious condition by the efforts of trainers and physicians.’

The occasion referred to by the Mercury’s shocked and disapproving correspondent was a six-day bicycle race held at Madison Square Gardens, New York, in 1897 – a largely-forgotten type of cycling competition that, in its heyday from the early 1900s till the late 1940s, catapulted many cyclists to the status of superstars and packed thousands of fans into specially constructed outdoor velodromes and smoke-hazed exhibition halls.

Competing in these events, among the most extreme in sporting history, demanded levels of courage and endurance from those cyclists (men and women) who participated which, compared to contemporary sporting events, stretch the boundaries of imagination. As an example of the kinds of performances cyclists achieved during six-day races, a useful yardstick of measurement can be drawn by comparing the distances of up to and over 4,000 kilometres cycled by two-rider teams over the six-day period to those ridden in the 2013 Tour de France of 3,200 kilometres where teams of nine riders competed over a period of 21 days.

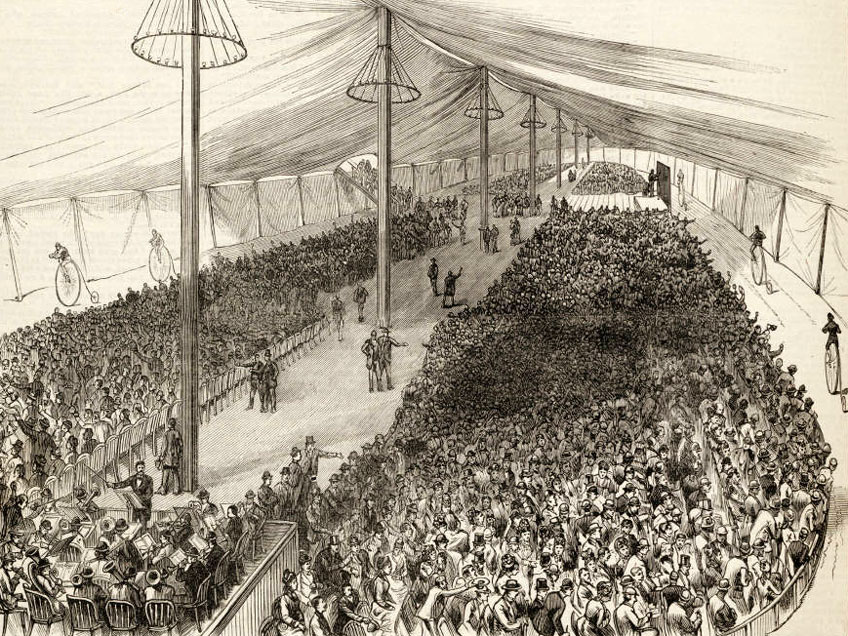

Beginning in England in 1878, with the first race in Australia held at the Exhibition Building in Melbourne in December 1881, six-day races originally consisted of individual contestants on penny-farthings striving to complete as many laps as possible around a banked track for twelve hours a day over six days. In these early races, riders slept after each day’s competition and rejoined the race each day at a time of their own choosing. Competitions were limited to six-days because of religious traditions requiring people to spend their Sundays in prayer and contemplation.

Source: SixDay.Org. http://www.sixday.org/html/usa_19th_century.htm

From around 1890, in order to achieve greater distances and to continue to break records, riders began to limit their periods of sleep, sometimes riding up to twenty-three hours a day in order to stay ahead of their rivals. These races became increasingly gruelling and physically demanding events, involving feats of endurance in which riders often collapsed or became delirious. The seeming brutality of the events led to a barrage of criticism in newspaper editorials and reports.

Writing from New York in 1896, our erstwhile Mercury correspondent deplored six-day races where [competitors’] ‘cheeks grow hollow, their eyes sink deep in the head, their feet swell, and all the outward symptoms are those of approaching insanity’. The outraged correspondent called for ‘all … parties connected with the show [to] be indicted and severely punished.’ (The Mercury, 14 March 1896, p.2).

These sentiments were repeated in an editorial in an 1897 edition of the New York Times:

An athletic contest in which the participants “go queer” in their heads, and strain their powers until their faces become hideous with the tortures that rack them, is not sport, it is brutality. (New York Times, 11 December 1897)

Nevertheless, despite doubts expressed by Doctors Cyrus Edsen and T Hamilton Birch, that cyclists who took part in these events had undoubtedly ‘shortened their lives’ and would ‘not recover from the state of exhaustion into which they have brought their physical and mental powers by their frightful exertion and … lack of sleep during their six days of torture’, most survived and went on to live long and healthy lives.

The groundswell of opinion against six-day racing grew to such an extent that, by 1899, New York and Chicago had passed laws outlawing races of more than twelve hours per day duration. To circumvent these limitations, teams of two riders competed, with one rider required to be on the track at all times, allowing the other to rest and to eat. Race winners were those who completed the most laps in the six-day period.

Reports of six-day races held in Australia can be found in newspapers from 1881 till 1890; however these earlier events appeared to have faded from public memory as the ‘first’ six-day race was later reported to be held at the Sydney Cricket Ground in January 1912 when 14 teams of riders from around the world competed for total prize money of £1000. Cheered on by an estimated crowd of 58,000 fans, the race was won by all-Australian teams – Alf Goullet who teamed with Paddy Hehir, in first place, with Alf Grenda and Gordon Walker, second and Reggie McNamara and Frank Corry, third. Six-day races continued in Australia for many decades with the last race recorded in Perth in 1989.

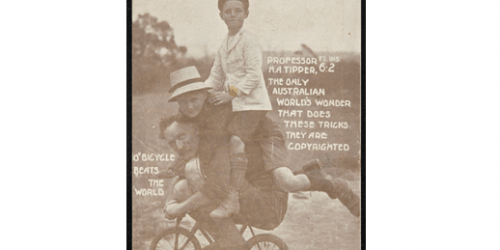

Source: Collections of the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Many Australian cyclists left the country in the early 1900s to compete and to make their fortunes in six-day races in the United States and Europe. Among these were Alf Goullet, deemed by some to be the greatest six-day racer of his time, and his team mate, Alf Grenda, of Tasmania, who in 1914 at a six-day track event in Madison Square Garden covered 2,759 miles (4,440 kilometres) to set a world distance record which remains standing today.

Source: US Library of Congress, George Grantham Bain collection

Another outstanding Australian competitor in international competitions was world-record holder, Reggie McNamara, pictured below (left) who won the 1912/13 Australian six-day race before going on to win 19 six-day races in the U.S and Europe between 1918 and 1933.

After coming second in the 1920 Goulburn to Sydney Road Race and achieving fastest time, N.S.W. champion cyclist, Ken Ross, joined a growing band of young, talented cyclists who had left Australia intent on trying their luck on the world cycling stage. In 1921, Ross and fellow cyclist, Jerry Halpin, sailed to a war-ravaged Europe emerging at the time from the devastation of the The Great War. The two young Australians competed in France, Belgium and Italy and were members of the first British sporting group to enter Germany since its fall in 1918. Ross enjoyed considerable success in Europe, notably in the 1922 Berlin six-day race and later in his impressive win over the, then reigning, world champion pursuit rider, Oscar Egg, from Switzerland. He returned to Australia in 1922 and later went on to win three Australian six-day races between 1922 and 1930. His story and details of his collection which is held by the National Museum can be accessed on our Collection Highlights‘ page.We would also welcome any further stories or information about Australians who competed in six-day races either here or overseas.

Today, six-day races are predominantly held in Europe in cities such as Rotterdam, Berlin, Zurich and Ghent. These races continue to draw large crowds of spectators, however distances covered over the six days are much shorter – around 800-900 kilometres – and cyclists compete in events such as the ‘Madison’, a tag-team cycling race over an eight hour period that takes its name from Madison Square Garden where six-day racing orignated in the U.S.

- Featured Image: This image shows Australian cyclist, Ken Ross, centre, with his trainer, right, and Belgian cycling champion, Emile Aerts. The photograph was taken after the finish of the Berlin six-day race in February 1922. According to Ross, ‘the Sydney Six-Days race … was only a training ride alongside of these’.