A piece of the ‘goodwill rock’

Tonight, a lunar surface fragment from the National Museum’s collection will appear in the Stargazing Live series, hosted by Professor Brian Cox and Julia Zemiro. Broadcast on the ABC from the Siding Spring Observatory, near Coonabarabran, New South Wales, the moon rock fragment will offer stories from the Moon, NASA astronauts and international politics, as leading scientists and personalities tackle astronomy’s most intriguing questions and seek to inspire Australians to explore our solar system. Next week it will be on display in the Museum’s Hall, a chance to see a small piece of the moon that captures a small moment in history.

This lunar surface specimen is a fragment of a larger basalt rock collected during the Apollo 17 mission, the eleventh and final manned mission of the American Apollo space program. Beneath the specimen is a small Australian flag, which was carried on board throughout the Apollo 17 mission to the moon and back.

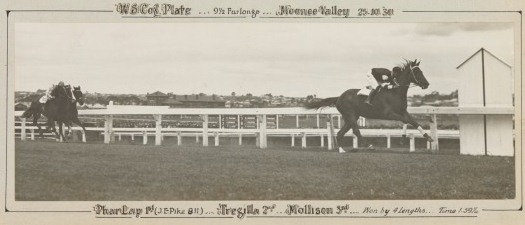

Astronauts Eugene Cernan and Harrison ‘Jack’ Schmitt spent 75 hours on the Moon’s surface, based at the Taurus-Littrow landing site, and gathered 110.4 kilograms of lunar samples. The original rock specimen, ‘basalt sample 70017’, and later known as the ‘goodwill rock’, was a composite of debris fragments blasted out of lunar craters by meteor impacts and volcanic activity, and considered to be billions of years old.

Schmitt, a geologist, was the first and only scientist to walk on the Moon. He organised the lunar science training for the Apollo astronauts, joining the Scientist-Astronaut program in 1965, and was designated Mission Scientist in support of the Apollo 11 mission. [1]

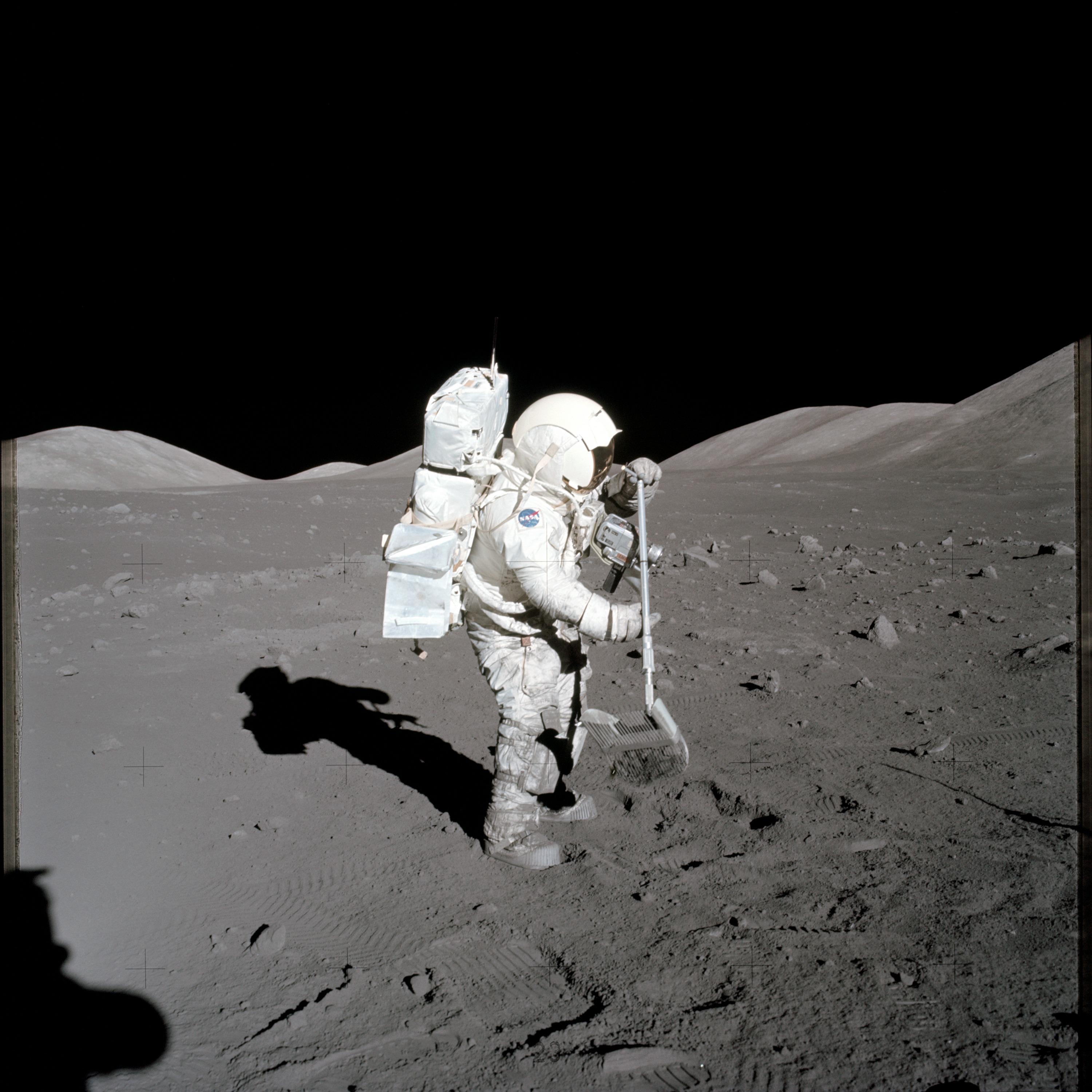

Schmitt collects lunar rake samples at Station 1 during the mission’s first spacewalk at the Taurus-Littrow landing site. This picture was taken by Cernan. NASA

A rock composed of many fragments

Cernan and Schmitt singled out ‘sample 70017’ for its particular geological properties, from all the material they had collected, and they shared its message with NASA Mission Control and the people of Earth before they left the moon on 14 December:

Eugene Cernan: Houston, before we close out our [moonwalk], we understand that there are young people in Houston today who have been effectively touring our country, young people from countries all over the world, respectively, touring our country. They had the opportunity to watch the launch of Apollo 17; hopefully had an opportunity to meet some of our young people in our country. And we’d like to say first of all, welcome, we hope you enjoyed your stay.

Second of all, I think probably one of the most significant things we can think about when we think about Apollo is that it has opened for us – ‘for us’ being the world – a challenge of the future. The door is now cracked, but the promise of the future lies in the young people, not just in America, but the young people all over the world learning to live and learning to work together. In order to remind all the people of the world in so many countries throughout the world that this is what we all are striving for in the future, Jack has picked up a very significant rock, typical of what we have here in the valley of Taurus-Littrow.

It’s a rock composed of many fragments, of many sizes, and many shapes, probably from all parts of the Moon, perhaps billions of years old. But fragments of all sizes and shapes – and even colors – that have grown together to become a cohesive rock, outlasting the nature of space, sort of living together in a very coherent, very peaceful manner. When we return this rock or some of the others like it to Houston, we’d like to share a piece of this rock with so many of the countries throughout the world. We hope that this will be a symbol of what our feelings are, what the feelings of the Apollo Program are, and a symbol of mankind: that we can live in peace and harmony in the future.

Harrison ‘Jack’ Schmitt: A portion of [this] rock will be sent to a representative agency or museum in each of the countries represented by the young people in Houston today, and we hope that they – that rock and the students themselves – will carry with them our good wishes, not only for the new year coming up but also for themselves, their countries, and all mankind in the future.

Working on the Moon

After returning to Earth, Cernan and Schmitt reflected on the historical significance of their work and the material they collected:

Cernan: Apollo 17 built upon all of the other missions scientifically. We had a lunar rover, we were able to cover more ground than most of the other missions. We stayed there a little bit longer. We went to a more challenging unique area in the mountains, to learn something about the history and the origin of the moon itself.

Schmitt: It was the most highly varied site of any of the Apollo sites. It was specifically picked to be that. We had three-dimensions to look at with the mountains, to sample. You had the Mare basalts in the floor and the highlands in the mountain walls. We also had this apparent young volcanic material that had been seen on the photographs and wasn’t immediate obvious, but ultimately we found in the form of the orange soil at Shorty crater. We found the oldest rock that’s been sampled on the Moon at the base of the South Massif.

In completing their work, Cernan and Schmitt set new records for time spent on the lunar surface and the amount of material collected:

Cernan: The lunar rover was a tremendous asset. One of the things that we knew was going to give us problem was the lunar dust, the soil, very fine. Almost like graphite. And you throw it up. When you drive the rover it would throw up like a rooster tail… We looked like coalminers. You’ve seen pictures of me. I’ve got black lunar dust all over the place.

Schmitt: I found the [scoop] much more versatile. I could pick up rocks with it – small rocks – but I could also dig trenches and do all sorts of other things with it. So, the scoop was perfectly fine for me; and it gave me something to lean on, to look down… [As for the tongs] – the spring would close them on a sample and you could lift it up; a scoop to get the soil samples. Just very simple geological tools, which have worked well through several hundred years and probably will continue to work several hundred years in the future. But still, it requires a great deal of human action.

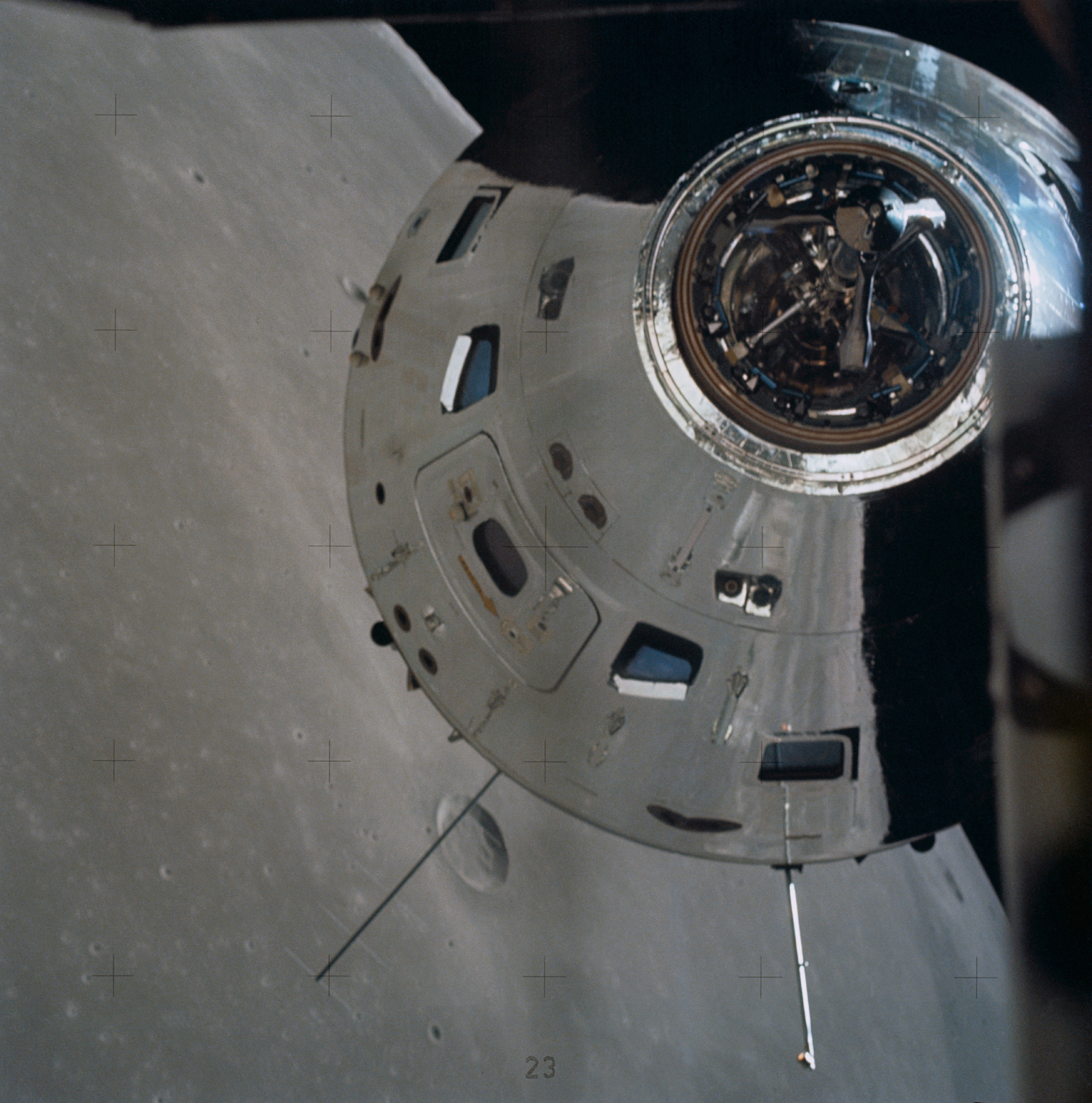

As he left the Moon, Cernan signed off with these words: “America’s challenge of today has forged man’s destiny of tomorrow. As we leave the moon and Taurus-Littrow, we leave as we came, and, God willing, we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind.” This photo shows the Apollo 17 command and service module as it prepares to rendevous with the lunar module. NASA

Return to Earth

In 1973, American President Richard Nixon ordered the distribution of fragments from ‘sample 70017’ to 135 foreign heads of state, an action that dubbed it the ‘goodwill rock’. The presentation to Prime Minister Gough Whitlam recognised Australia’s contributions to the Apollo program, with its three National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) tracking stations located in the Australian Capital Territory maintaining communications with spacecraft.

A letter dated 21 March 1973, signed by President Nixon, accompanied the samples:

The Apollo lunar landing program conducted by the United States has been brought to a successful conclusion. Men from the planet Earth have reached the first milestone in space. But as we stretch for the stars, we know that we stand also upon the shoulders of many men of many nations here on our own planet. In the deepest sense our exploration of the moon was truly an international effort.

It is for this reason that, on behalf of the people of the United States I present this flag, which was carried to the moon, to the [Nation], and its fragment of the moon obtained during the final lunar mission of the Apollo program.

If people of many nations can act together to achieve the dreams of humanity in space, then surely we can act together to accomplish humanity’s dream of peace here on earth. It was in this spirit that the United States of America went to the moon, and it is in this spirit that we look forward to sharing what we have done and what we have learned with all mankind. [2]

Between 1969 and 1972 six Apollo missions brought back 382 kilograms (842 pounds) of lunar rocks, core samples, pebbles, sand and dust from the lunar surface. The six space flights returned 2,200 separate samples from six different exploration sites on the Moon. [3]

The rock and plaque were transferred to the National Museum from the Department of Science and the Environment in 1980.

The National Museum’s collections also include material from the Orroral Valley Tracking Station, equipment used at the Australian Centre for Remote Sensing, and a fragment of a propeller used on the aircraft Southern Cross, taken into space by Australian astronaut Andy Thomas on STS-102 Discovery (March 8-21, 2001), the eighth Shuttle mission to visit the International Space Station.

This fragment of the ‘goodwill rock’ will be on display at the National Museum next week after it has been part of Stargazing Live. Join the conversation #StargazingABC

[1] Biographical details for scientist-astronaut Harrison ‘Jack’ Schmitt and further reading on the Apollo 17 mission.

[2] Letter content as reproduced from the National Archives.

Quotations from the oral histories of Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt, NASA.

Feature image: 11 December 1972 – Astronaut Eugene Cernan, makes a short checkout of the Lunar Roving Vehicle during the early part of the first Apollo 17 extravehicular activity (EVA-1) at the Taurus-Littrow landing site. This view of the ‘stripped down’ Rover is prior to load-up. This photograph was taken by Harrison Schmitt. The mountain in the right background is the East end of South Massif. NASA

Very interesting to read. Since I was a kid I’ve always had a fascination with the lunar landing program. Nice to see some new pictures.