The Path of the Bogong: Land & People

My name is Patrick Bailey. This is the final of three posts that I’ve prepared as an intern at the National Museum of Australia (and as part of the Australian National Internship Program), which explores how the interaction between human and non-human forces in Southern NSW and the ACT combine to form continual and changing expressions of community identity. This last post will explore how the land has been influenced by people and formed ongoing relationships which resonate with inhabitants today.

Pastoralism

One of the more common stereotypes of alpine Australia involves the presence of brumbies and cattle, and their impact on the environment. However, these two animals are only a recent addition to the region. Until Europeans arrived, no such animals existed here. These new species, along with rabbits, dogs and sheep, and plants such as wheat and barley, changed the landscape forever. It was not until the 1850s however, that pastoralism really morphed the environment. From the 1850s, pastoralists developed new and innovative ways to cultivate the land. One technique was the use of the alpine zone during summer. This opened up a great swath of fertile land for cattle, sheep and horses which had not previously been used for animal husbandry. Horses allowed people to traverse the landscape unlike they had ever been able to do. The implementation of snow leases in 1884 under the Land Act further transformed the landscape into one more controlled by people. With the introduction of new species and the rigorous grazing of the high country, the land underwent significant changes which included severe soil erosion, loss of biodiversity and the spread of animal ‘pests’.

Despite being divided over this issue, many local communities believe these animals represent the heritage of pastoralism in the region and are an example of living heritage, where their presence is a constant reminder of how the environment has given life to new forms of identity and human/non-human interaction.

Gold Mining

Perhaps the most significant immediate impact on alpine Australia was the discovery of gold in the 1850s at Kiandra. This led to a gold rush in the region, with estimates of over 10 000 people converging on the area. Only lasting approximately two years (1859-1861) the impact of this sudden wave of (and equally sudden exodus of) people profoundly changed the environment and human interaction with it forever.

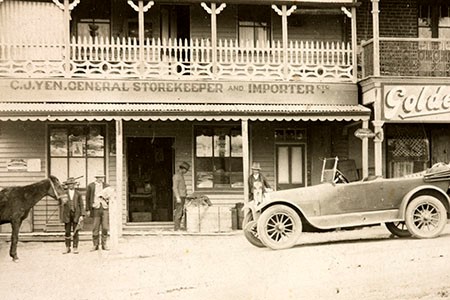

Of these 10 000 immigrants, over 700 Chinese migrants settled in Kiandra as mining labourers, graziers and shop owners. One family in particular, the Yen family, is notable for being a focal point of the Old Adaminaby community. The CJ Yen collection at the NMA contains many artefacts ranging from sophisticated women’s apparel to food products and skiing equipment. These artefacts represent a general trend amongst Chinese immigrants, with a large assortment of imported goods such as tea. Other artefacts included women’s crochet gloves, tailored towards a middle class patron. The diversity in the collection also represents the diversity of Old Adaminaby and other alpine districts, where a varied range of people would live together.

CJ Yen’s general goods store in Old Adaminaby, courtesy Odette Yen,

National Museum of Australia

A phenomenon, whilst not iconic to Kiandra alone, was the seasonal basis of mining. During the summer months when the land was vibrant and the soil fertile, the ‘miners’ would become the ‘farmers’ or ‘pastoralists’ in order to best be accommodated with the land. During the winter months or those less equitable for farming, these groups would become ‘miners’ once again. This seasonal rotation was singularly influenced by the environment and directed the occupations of the people whom relied on the seasons. It is the connection to land and community established by groups of people, such as the Yen family, which transformed the alpine environment into a diverse landscape. The result was the establishment of communities which gained their connectivity and identity through their direct connection to the surrounding environment. In this way, non-human forces directed a means of subsistence and community which became iconic of its own region.

Water Harvesting

Possibly the most significant long term impact on the alpine environment was the manipulation of water throughout the region. In particular the construction of the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme unequivocally transformed the environment. Hitherto the construction of hydro-electric power programs, human interaction with the land was directed by the natural contours of the environment: the flow of the rivers, the curve of the hills and the sheer faces of the mountains. Hydro-electric power programs changed the relationship humans had to the non-human environment. Humans were now directing environmental activities at an unprecedented scale. Constructed between 1949 and 1974, the Scheme required the services of over 100 000 people from over 30 different countries. It contains 16 dams, 12 tunnels totalling 140 kilmetres and 7 power stations (the largest of which, Tumut 3, provides 1.5 million kilowatts of electricity per year). The impact of this scheme is best summarized as: ‘The Snowy Mountains Scheme altered the countryside to such a vast degree that it formed its own landscape’ (Snowy Mountains Scheme, Office Of Environment And Heritage).

Map of Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme. Source: Wikipedia

Conclusion

The alpine region of Australia encapsulates a dynamic interplay between human and non-human forces over hundreds of years. It is the bond formed between human interactions with the environment that has made the relationship an ongoing syncretic dialogue. This communion was first established by the Aboriginal people of southern NSW and the ACT over 21 000 years ago and, while some of their traditions and ceremonies have been lost, the influence of the land and the traditions and identities gained from it are long lasting. Whether it is through alpine skiing, bushwalking or conservation movements, this relationship is maintained. People such as Tom and Jean Moppett and Myles and Milo Dunphy are just some of the many people who have gained a sense of identity and belonging from their connection to alpine land. Other ventures, including pastoralism, mining and water harvesting have changed the environment to suit more human desires, yet the relationship with the land is similarly iconic of the region, and has formed many communities’ identities, such as at Adaminaby and Kiandra. It is through our connection to land that we are able to connect to the wonders of the land and enjoy the beauty which makes alpine Australia and its communities unique in the world.

For me this research has driven me to really think about my impact on the land and how the land has impacted me. I look at the collections held within the NMA and other artefacts of the alpine region and think to myself: this land has driven people together, has manifested identities and engaged core human values, particularly wonderment. What can we learn from our interaction with the environment? What can it teach us if we actively engage with it and respond to it?

Top image: Snowy Mountains, December 2012, Flickr Creative Commons.

[1] KHA – Dicky Cooper Hut, Kosciuszko Huts Association. Available from: http://www.khuts.org/index.php/the-huts/kosciuszko-national-park/710-dicky-cooper-hut

[2] Deirdre Slattery, Australian Alps: Kosciuszko, Alpine and Namadgi National Parks, CSIRO Publishing, 2015.

[3] Josephine Flood, The Moth Hunters: Aboriginal Prehistory of the Australian Alps.

[4] Andrew Denning, Skiing into Modernity: A Cultural and Environmental History, Oakland, University of California Press, 2014.

[5] Daniel George Moye, Historic Kiandra: a guide to the history of the district, Cooma, Australia.

[6] World Heritage Encyclopedia, Kiandra Pioneer Ski Club, Project Gutenberg. Available from: http://gutenberg.us/articles/kiandra_pioneer_ski_club

[7] Elyne Mitchell. A Vision of the Snowy Mountains, South Melbourne, Macmillan of Australia, 1988.