From paddock to pate: ‘good Australian felt’

In time for Australia Day, January 26, dig into the story behind that peculiarly Australian icon of headwear: the rabbit fur felt hat.

This post is the third in a series co-developed by Jono Lineen and other curators that explores Australians’ experiences with rabbits through objects in the National Museum’s collections.

Infamous here as pests on the land, Australia’s wild rabbits achieved international fame for their contribution to fashion. From the late nineteenth century many millions of rabbits took on new identities as coats and hats, a furry and felty invasion welcomed in cities and towns around Australia and overseas.

The soft under-fur from European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) caught in Australia was found to produce high quality felt, a robust and easily mouldable material popular for (mostly) men’s hats. Animals traditionally used for hatter’s felt in the nineteenth century, such as North American beaver, were becoming increasingly scarce, and hats made from that fur more expensive. Antipodean rabbits, however, looked to be in limitless supply. Once discarded rabbit pelts came to be in demand as hat-makers in Australia and elsewhere caught on. Aside from local use, a valuable export trade developed early in the twentieth century with billions of pelts shipped to buyers in Britain and North America where they were transformed into fashionable hats and furs.

When we raise our hats to ladies nine times out of ten we make a gesture of respect to the rabbit … since the despised Australian bunny contributes in its millions to millions of hats.

Correspondent to the Perth Daily News, 23 August 1929

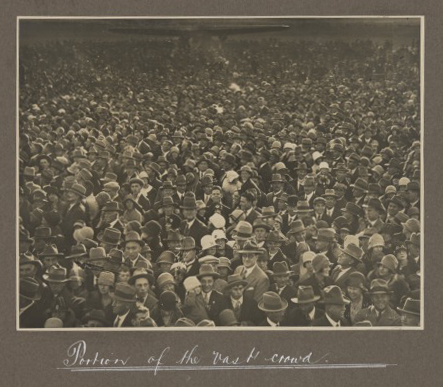

Austin Byrne ‘Southern Cross’ Memorial collection. National Museum of Australia. Reprography by Jason McCarthy.

State Library of NSW BCP02392

Valuable vermin

Whilst rabbit meat sold well at the markets, pelts – at first – attracted little commercial interest. Yet by the 1880s, Australian rabbit skins were being auctioned in their millions in London, a centre for felt- and hat-making. In Australia, hat-makers established themselves where rabbits were most plentiful: in Tasmania, Victoria (where, according to Warwick Eather and Drew Cottle’s recent study, the number of hat manufactories doubled between 1870 and 1880) and in New South Wales.

Whatever the Australasian pastoralist may think to the contrary, the world cannot do without Australasia’s rabbits.

Percy O Lennon, The Queenslander, 1929

From the start of the twentieth century to nearly 1950, Australian hatters and furriers bought around one billion rabbit skins, however most were still shipped overseas. Over this time, the majority of export skins went to North America, where buyers sought rabbits as cheaper alternatives to, and even substitutes for, luxury furs such as sable. With creative preparation, rabbit pelts could be made to look like (and were successfully sold as) fashionably desirable furs. Accordingly, rabbit skin prices rose dramatically. Australian papers duly reported on potential increases in the cost of hats, then a widely worn item of men’s fashion. Demand was such that anyone able to catch rabbits could make money by selling skins.

National Library of Australia nla.pic-vn6253643

Though skins were enthusiastically received by hat-makers and furriers, live rabbits continued to be a considerable problem in rural areas. Rabbits ate pastures bare, removing feed for sheep and cattle and forcing many farmers to sell their stock and even abandon their properties. Once-cheap rabbit pelts began to outprice wool, also used in hat-making, prompting speculation of a possible return to wool headwear. A writer for Melbourne’s Argus newspaper noted in 1908 that ‘The rabbit … competes with the sheep, not only on the land, but in the market’. In 1930, another writer concluded that ‘[b]y wearing a good Australian felt, one aids in checking the advance of the rabbit, thereby benefiting farmers and graziers’; and wondered, charitably perhaps, whether rabbits could be considered a ‘beneficent pest’, given the many jobs associated with the hat-making industry – trappers, carriers, ‘factory hands, chemists, dyers, engineers, mechanics and repairers’.

Hatter’s fur

Furriers and hat-makers preferred pelts with winter fur, as this was thicker and softer than fur grown by animals during warmer months. Rabbits caught for their fur were usually trapped or poisoned (shooting required accuracy so as not to damage the skin), then packed and transported to markets. In rural areas away from refrigeration, skins were removed from the carcass straight away, turned inside-out and stretched for drying. Once dry and flat, they were sold to a skin merchant for later auction or sale to fur processors and hat makers in Australia or overseas. Skins were graded and packed into large bales (similar to wool) for shipping.

Courtesy Royal Australian Historical Society (RAHS).

National Archives of Australia A1200, L2657.

Observers reported that fur cutters in England preferred working with Australian skins due to the quality of the fur, and the skilful and consistent way trappers prepared and stretched the skins. Eric Rolls commented in his book They All Ran Wild that ‘…English skins should have been superior, since the fur grows more thickly in the colder climate, but the game-keepers, farmers, and poachers were unskilful skinners, and as they did not stretch their skins to dry they were rumpled and untidy.’

On the journey to becoming hats, rabbit pelts could travel many thousands of kilometres. After being caught in paddocks, transported to town then to market in cities, some rabbits – bought as pelts by overseas buyers – returned to Australia as processed felt (in preparation for hat manufactories) or as ready-made furs.

Making hats

The simple form of a fur felt hat belies the many steps involved in its making. Rabbit pelts destined to become hats experienced a great array of processes involving pressure, air, heat, steam, chemicals and other additives. As a Melbourne newspaper explained it in 1934:

A brief summary of the processes through which a fur felt hat must pass reveals some twenty-seven distinct operations, from the early fur cutting, blowing, forming, hardening, settling, crazing, bumping, dyeing, stamping and pouncing, down to such later finishing processes as steaming, pressing, curling, rounding, trimming, velouring and the packing of the finished article.

Sam Hood collection, State Library of New South Wales hood_06299

The first operations saw long outer hairs removed from the pelts and soft under-fur separated from the skin. This soft fur was then processed and formed into cones which were shrunk to knit the fibres together into a dense-texture felt. The felt was dyed and shaped and the brim stretched to size. Finishing steps involved polishing the felt, final blocking of the crown and shaping of the brim, then trimming with hatband and lining.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century parts of the overall process were mechanised. Specialised machines were developed for trimming the outer hair tips from the pelts (such as Benjamin Dunkerley’s machine), cutting fur from skins, rolling, steaming, stretching and stitching. Prior to this, laborious tasks such as cutting the hair tip from the fur had to be done by hand. using a small knife. Typically women were employed in skin and fur-processing factories to do this type of intricate and detailed work.

‘Madness’ and beer

Various chemicals were applied to fur to assist knitting of the fibre and smoothing of the felt, such as nitrate of mercury, sulphuric and other acids. Until its toxicity was discovered, prolonged exposure to nitrate of mercury could cause a range of health problems for hat-makers, leading to symptoms of the so-labelled ‘mad hatter’s disease’. The hat-making process also resulted in by-products – skin scraps and hair – which went to make glue, gelatine (used in foods such as sweets and jams), and fertilizer. Visitor to a London fur-processing factory in 1929, Percy Lennon highlighted an important use of ‘hair manure’ for readers of The Queenslander:

‘Nothing whatever goes to waste. Rubbishy hair and factory sweepings contain just the right percentage of ammonia and other ingredients to make first-class fertiliser; which fact is duly appreciated by the hop-growers of Kent, who buy the stuff in bales and top-dress it on their gardens every September, thereby reaping increased harvests the following year. In such wise are the furred pests of the Antipodes responsible for more and better British beer.’

National Museum of Australia. Photo by Katie Shanahan.

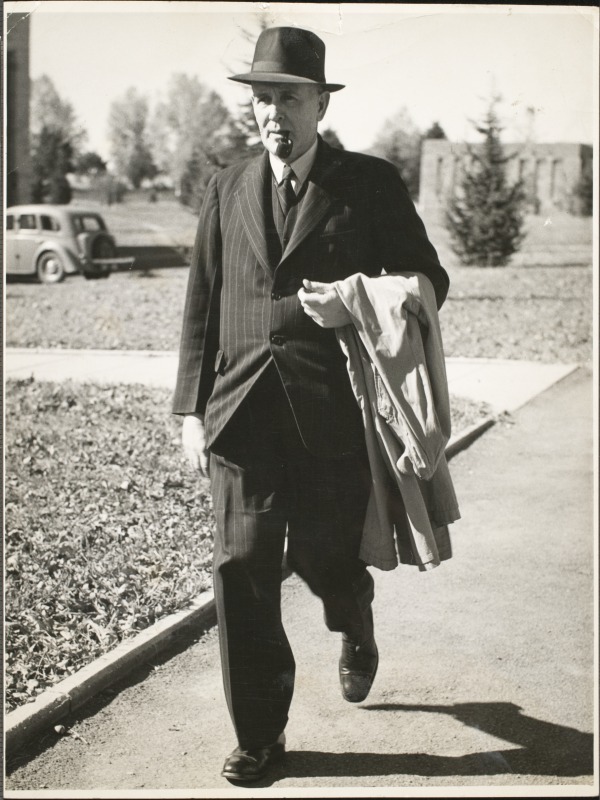

A notable hat and wearer

Joseph Benedict ‘Ben’ Chifley (1885–1951) was Australia’s 16th prime minister, from 1945 to 1949. During this relatively short time Chifley’s government made a number of significant achievements. These included the establishment of the Snowy Mountains Scheme, the founding of Australia’s national security service (ASIO), the Australian National University, Australia’s post-war immigration program, the establishment of Trans-Australian Airways (TAA) and the nationalization of Qantas Empire Airways, the establishment of a separate Australian citizenship, and the introduction of social reforms aimed at increasing access to welfare payments. Chifley also unveiled Australia’s first locally made car, the Holden.

In keeping with men’s fashion of the time, Chifley regularly wore a hat. The example in the Museum’s collection was a style popular during the 1940s. It was made in Sydney by hat manufacturer Akubra, from the fur of about six rabbits. It is believed to have been worn by Chifley whilst gardening at his home in Bathurst, after it became worn in and less suitable for official duties.

Biographer David Day noted that ‘Chifley left an indelible image of a humble, self-effacing man who would rather have been digging in his garden than debating in parliament.’

Ben Chifley collection no.3, National Museum of Australia.

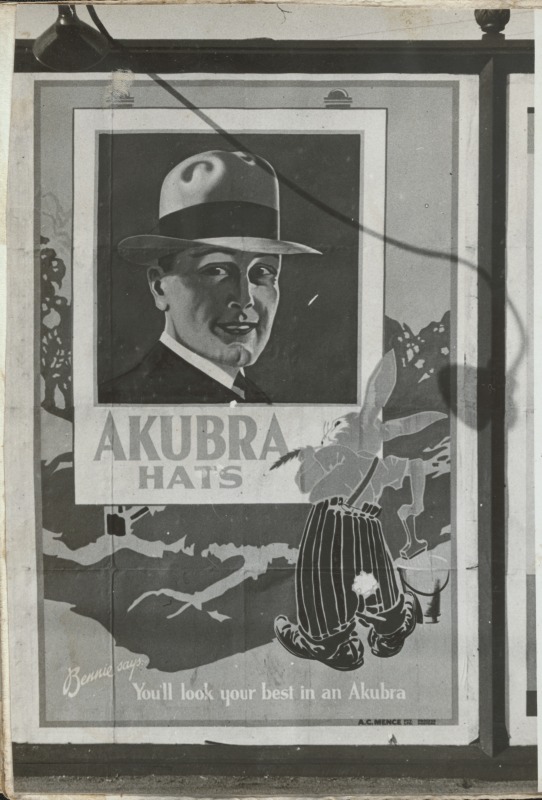

Akubra hats

In their 2010 essay exploring the symbolism of ‘Akubra’ in Australian society, Philippa Macaskill and Margaret Maynard argue that:

The Akubra broad-brimmed rabbit fur hat has assumed the role of one of Australia’s best loved symbols of nation. Worn as a practical accessory on the land, a stylish item for celebrities, a gesture to constituents by politicians and a part of popular leisure and tourist garb, the Akubra has become a virtual ambassador for ‘Australianness’.

Engineer and milliner Benjamin Dunkerley invented a machine to remove the hair tips from rabbit pelts, after he moved from England to Tasmania in 1874. In the late 1880s, Dunkerley moved to Sydney and went into business with retailer Arthur Pringle Stewart, and later, Manchester hat-maker Stephen Keir (who married Dunkerley’s daughter, Ada). In 1911 the company changed its name to Dunkerley Hat Mills, and in 1912 registered the ‘Akubra’ trademark. Over the following decades, this trade name became famously associated with rabbit fur felt hats.

Bothwell Museum collection, National Museum of Australia. Photo by Katie Shanahan.

Akubra’s business boomed during the First World War with Dunkerley being one of the manufacturers producing ‘slouch’ hats for Australian soldiers. When Dunkerley died in 1918, Keir took over as managing director and moved to the factory from Surry Hills to much larger premises at Waterloo. Output of hats was increased and the company prospered. In 1974 the factory relocated again to its current premises at Kempsey, on the mid-north coast of New South Wales, where operations involved fur-processing as well as hat-making.

In recent times, despite the continued presence of rabbits (still considered ‘one of the most widely distributed and abundant mammals in Australia’), obtaining and processing skins locally has become more costly than importing pre-processed fur from overseas. In July 2015, Akubra announced that future hats would be made with imported rabbit fur.

More rabbits at the National Museum

The Old New Land gallery features rabbit-related objects from the Museum’s collections, including a syringe used in myxomatosis trials, rabbit traps, a rabbit skin rug, and sections from Western Australia’s rabbit proof fences.

Rabbit-related objects in the Museum’s Collection Explorer.

Further reading

Warwick Eather and Drew Cottle, ‘The Rabbit Industry in South-East Australia, 1870-1970’ in Phillip Deery and Julie Kimber (eds) Proceedings of the 14th Biennal Labour History Conference, Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, Melbourne, 2015.

Philippa Macaskill & Margaret Maynard, ‘Akubra’ in Melissa Harper and Richard White (eds), Symbols of Australia: Uncovering the stories behind the myths, University of New South Wales Press and National Museum of Australia Press, 2010

Eric Rolls, They All Ran Wild: The Story of Pests on the Land in Australia, Angus & Robertson, 1977.

Williams et al, 1995; referenced in Commonwealth of Australia, Department of the Environment, ‘Draft Threat abatement plan for competition and land degradation by rabbits’, October 2015