‘Southern Cross’ lands in Canberra: aerial politics

As the crew of the ‘Southern Cross’ celebrated their trans-Pacific flight in June 1928, aviation was changing Australia’s environmental and political landscapes. On 15 June, they flew from Melbourne to Canberra, arriving at the recently established aerodrome during the early afternoon and receiving an enthusiastic reception by locals, government officials and returned servicemen. Riding the wave of their success and popularity, Charles Ulm and Charles Kingsford Smith had big plans, and this and their future visits to Canberra would be strategic.

A visit to the federal capital

The ‘Southern Cross’ was delayed in its departure from Melbourne on the morning of 15 June 1928. There was some disappointment in Canberra when the aircraft arrived with its famous crew several hours later than expected. However, a cheering crowd of staunch fans was at the aerodrome to see the ‘Southern Cross’ and crew, and listen to the official speeches. Located at the corner of Majura Valley Road and the Queanbeyan-Duntroon Road, the Canberra aerodrome was then only an open paddock, leased from the Campbell family in 1927 and still used for grazing.

Kingsford Smith and Ulm were the most famous aviators to have visited the new aerodrome. On a small platform, erected for the occasion, Prime Minister Bruce handed Kingsford Smith and Ulm a cheque for £5,000, and delivered a short speech: “As you have rightly said, aviation is not something which can be expressed in commercial terms. It is far bigger than that. No man can measure the value of your achievement and no Government can adequately express the feelings of its people in praise of your accomplishment”. [1]

The Prime Minister was rushed away to travel to Sydney, but the remainder of the official party were driven to Parliament House for afternoon tea – in place of what was to be a lunch reception for the aviators. During the round of speeches, the achievements of the trans-Pacific flight were framed in national terms, with Senator Pearce stating, on behalf of the Prime Minister, “You have made Australia once more the centre of the world’s interest”, and “You have forged other links in the chain of friendship between the two great republics of Australia and America”. [2]

Ulm and Kingsford Smith replied by restating their plans to continue flying and promoting the benefits of air travel. In his speech, Ulm said that “the [trans-Pacific] flight had made the public sit up and take notice of aviation”. [3] Ulm also took the opportunity to thank the government for their pledged support of their planned flights to New Zealand and across Australia.

The aviators were hosted at a reception by the Returned Soldiers League that evening, leaving Canberra early the next morning to return to Richmond and attend further receptions in Sydney.

Throughout the publicity following the trans-Pacific flight, the skills of each crew member were praised – Kingsford Smith as pilot, Lyon as navigator, Warner for his continuous wireless contact and Ulm for his organising abilities. When publishing his book ‘The Old Bus’, Kingsford Smith included this dedication: “To my old flying colleague, Charles T. P. Ulm, without whose genius for organisation and courageous spirit many flights in the ‘Southern Cross’ could never have been achieved”. Though they worked in partnership, it would be Ulm’s organisation skills that would underpin and be called into question on all subsequent flights and throughout the short life of their company, Australian National Airways Ltd (ANA).

ANA services to and over Canberra

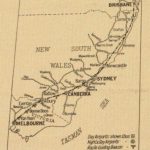

When Ulm and Kingsford Smith established ANA in December 1928, the primary objective of their company was to “operate a regular mail, passenger and freight service by air between Melbourne, Albury, Canberra, Sydney, Newcastle, Lismore and Brisbane”. After commencing services in January 1930, ANA began to attract a growing number of businessmen to the service, offering considerable time savings for the regular traveller at costs comparative to train tickets. The ANA Sydney-Canberra service was particularly attractive to Canberra politicians.

The daily Melbourne-Sydney flight passed over Canberra and Albury, following a route that allowed for emergency landings and refueling stops as necessary. In September 1930, an ANA flight from Sydney to Melbourne, piloted by James Mollison, was forced to land in Canberra after struggling in storms and heavy winds.

In July 1930, John T Harrison offered this account as a passenger on an ANA flight from Melbourne to Sydney in Aircraft magazine:

In the spacious cabin, well-heated and ventilated, with cotton wool for the ear drums, individual packets of Minties as protection against air-sickness, a liberal supply of morning newspapers, together with a thermos of coffee, such trifles as two hours of continuous blind flying and the formation of ice on the machine disturbed the passengers not at all. The cabin appointments leave nothing to be desired. The eight wicker armchairs are set in two rows. A centre isle allows plenty of room for moving about. Also there is plenty of headroom, even for six-footers and over (like the writer!). Fitted with sky-blue cushions, the chairs are quite comfy. Sliding windows are also arranged so that every passenger may have fresh air at will. [4]

The ‘Southern Cloud’ disaster

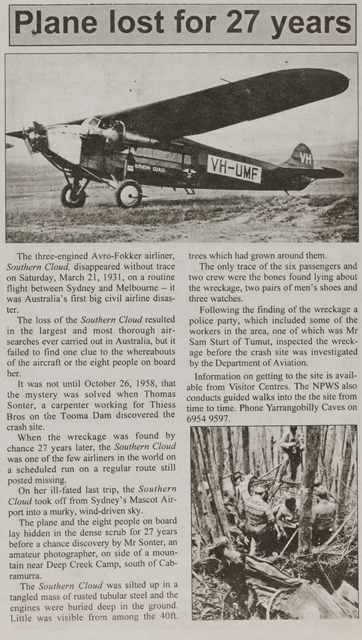

On 21 March 1931, six passengers boarded the ANA’s ‘Southern Cloud‘ on the scheduled flight from Sydney to Melbourne, for a departure time of 8:15 am from Mascot aerodrome: May Glasgow, housekeeper; Hubert Farrall, a businessman returning home; theatre stage producer Clyde Hood travelling to spend the weekend with his wife Bertha Riccado staring in JC Williamson’s Sons o’ Guns; Julian Margules, partner in a Melbourne electrical firm; and Bill O’Reilly, a young account making regular trips with ANA. [5] The crew, experienced pilot Travis Shortridge and apprentice pilot-engineer Charles Dunell, completed their preparations and lifted off on time having reviewed the Bureau of Meteorology’s forecast for cloudy and unsettled conditions across New South Wales.

When the aircraft failed to arrive for a scheduled refueling stop at Bowser field, north of Wangaratta, there was no cause for immediate concern as it was assumed that Shortridge had landed at an alternate aerodrome. Communication between aerodromes was limited, and with the ‘Southern Cloud’ was non-existent. It was not until late that night that Ulm was able to confirm the extent and severity of the weather that day across New South Wales and Victoria, and without word of the ‘Southern Cloud’s’ location, he issued orders to suspend ANA’s services for the next day and begin a search for the aircraft.

Extensive aerial and ground searches in Victoria and New South Wales, based on varied witness reports as to the last known location and likely trajectory of the ‘Southern Cloud’, failed to find any trace of the aircraft. As Macarthur Job states, “it was reluctantly concluded that the aircraft’s occupants could no longer be alive and the search effort was officially brought to a close”. An Air Accidents Investigation Committee Inquiry questioned the management and staff of ANA at length, concluding that the aircraft had likely been forced to land or had crashed as a result of severe weather.

The loss of ‘Southern Cloud’ and all crew and passengers was a severe blow to Ulm and Kingsford Smith. Ulm had lamented the lack of wireless services available in Australia to assist with navigation and communication for the safe process of aerial transport. He had requested permission to establish ground wireless stations along the ANA route between Melbourne and Brisbane to enable communication with flying aircraft, but were refused on grounds that such stations should be owned and operated by the Commonwealth. [6] It was only after the tragic loss of ‘Southern Cloud’ that new safety processes and procedures, including making two-way wireless communication standard for commercial aircraft, were implemented.

The end of ANA

The ‘Southern Cloud’ disaster, a sharp decrease in passenger numbers and financial difficulties attributed to the Great Depression, forced ANA’s directors to suspend all services in June 1931. Ulm attempted to save the airline, again visiting Canberra to seek government assistance in the form of a subsidy, and sought loans and partnerships in Australia and internationally. His efforts were ultimately unsuccessful and ANA entered voluntary liquidation in February 1933.

Reflecting on his time in negotiating the trials of commercial aviation in Australia, sometime during 1933-34, Ulm wrote:

I have watched, and played a part in, the struggles of aviation to establish itself as something more than the prosperous man’s past time and the sight-seers’ thrill, a kind of aerial vaudeville in which members of the audience are invited to ‘try their luck’. I have seen the excellent training of Aero Clubs and commercial flying schools producing pilots of high efficiency who, in their turn, could either swell the ranks of the joy-ride vendors or – if they were wealthy enough – take solo flying as a hobby. In a country of excellent flying conditions, a continent for which the aeroplane is the only logical medium of transit and defence, a surplus of trained pilots exists – idly kicking discontented heels – earthbound!

The aviation industry in Australia, fighting valiantly against the barriers of high costs, fretted with internal jealousies, and blind to its total lack of coherence, achieved that ‘patchy’ success which is akin to failure. Governments, realising – however vaguely – that the science and practice of aviation must not be allowed to die, and perceiving the value of certain air services must not be allowed to die, and perceiving the value of certain air services to isolated communities, principally in Western Australia and Queensland, had placed a financial prop beneath the economic structure of these services. There had been no concentrated and concerted effort to create a definite, clearly defined and well-founded public opinion in favour of a national effort in Aviation. The majority of newspapers demanding always a ‘story’, continued to feature exciting exploits and aeronautic idols; flying heroes (and none can belittle that they earned their hour of glory!) monopolised the microphones. Governments, well and truly aware of the absence of an active public opinion, feared – particularly in times of financial stress – to suggest a further measure of assistance from the public purse, even though that assistance might quickly enable Australia to lead the world in commercial and defensive flying. To preach the gospel of the national importance of a properly instituted and solidly organised aviation industry was to find oneself as a voice crying in the wilderness – or to be branded as a seeker after self-centred publicity. But one understood the difficulties – the difficulties of Statesmen, the difficulties of the aircraft operators, and the difficulties of the Press. Yet, continuously, the though persisted that public education on the vital necessity for a forward policy in relation to aviation should not be delayed – Depression or no Depression; that the aeroplane could play a tremendous part in the revival of commerce; that it was a reproach to Australia that it should depend on other nations for the carriage of its airmail, and that the whole trend of foreign affairs pointed to the urgent need for changing the nation’s viewpoint on aviation in its relation to Australia and New Zealand. [7]

Finding and remembering the ‘Southern Cloud’

It was not until 1958 that the wreckage of the ‘Southern Cloud’ was formerly identified, after being accidentally located by Tom Sonter, a carpenter working on the Snowy Mountains Scheme, while bushwalking on the Toolong Range, near Kiandra, New South Wales. Curious members of the public visited the site and souvenired pieces of the aircraft, several now part of the National Museum’s collections.

[1] ‘Pacific Flyers’, in Daily Advertiser, Wagga Wagga, 16 June 1928, p4.

[2] Cairns Post, 18 June 1928, p5.

[3] Cairns Post, 18 June 1928, p5.

[4] As published in Macarthur Job, Into Oblivion: the Southern Cloud enigma, Sierra Publishing, 2010, pp119-120.

[5] Summary of detailed information in Macarthur Job, Into Oblivion, pp42-43.

[6] Macarthur Job, Into Oblivion, p32.

[7] Charles Ulm, unpublished autobiographical manuscript, extracts in Ellen Rogers, Faith in Australia: Charles Ulm and Australian aviation.

Ulm’s RAAF uniform cane and a commemorative airmail box, from Ulm’s flight to New Zealand in December 1933, are on display in the Museum’s new acquisitions showcase until 23 August 2015.

For more information: www.nma.gov.au/collection/highlights/aviation

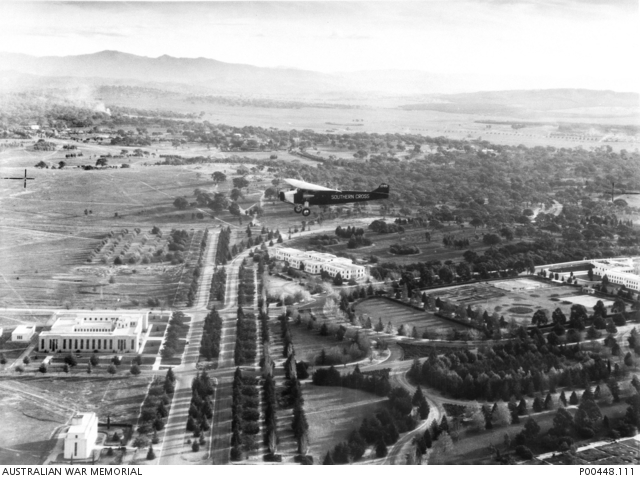

Feature image: ‘Southern Cross’ flies over Canberra in 1945, during filming for the film ‘Smithy’, reconditioned with its 1928 livery, including the ‘1985’ American registration. Australian War Memorial (P00448.111)