Rabbiting on

Last week, I talked to Mikey Robins about rabbits.

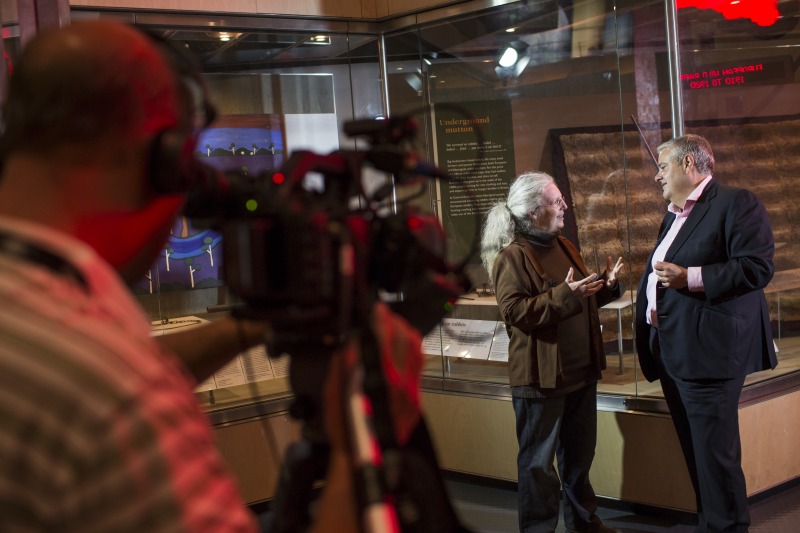

The writer and comedian visited the Museum to shoot a series of short films for the Defining Moments in Australian History project.

He talked to curators, donors and community members about objects in the National Historical Collection that illuminate significant events in our history: the cannon from HMB Endeavour, Ned Kelly’s Jerilderie letter, and Ngunnawal stone tools.

One of the eight objects Mikey chose was a rug made from the pelts of rabbits trapped by Ralph Parkes while jackerooing on ‘Merilla’, at Ilford, New South Wales, in 1934.

Learning how to trap and skin rabbits was an essential for 19-year old Ralph, a Sydney boy who dreamed of owning his own property. Given that hundreds of millions of rabbits had burrowed into nearly every corner of the Australian continent below 23 degrees south, wherever Ralph made his home, the rabbits would have got there first. Ralph would need to know how to contain and control them, whether with traps, dogs, fences, poison, fumigation or warren ripping. If he didn’t, his land could soon be worthless for grazing stock, as the rabbits ringbarked trees and shrubs, ate seedlings, chewed grass down to the roots and dug holes, until the soil washed or blew away.

Ralph dried the skins of the rabbits himself, and then sent them to his parents in Lindfield to make a rug for his mother. His father took the skins to a furrier, who used 70 to make the rug and kept the rest as part payment for the job. The rug was used by Ralph’s mother Mrs Elizabeth Parkes until the late 1950s when it returned to Ralph, who was by then a grazier living in Llangothlin NSW with his wife Emmie. It was then used by their son while he was studying at the University of New England.

The rug was donated to the Museum by Emmie Parkes in 2007. It’s on display in the Old New Land gallery, and is one of many remarkable objects relating to rabbits in the National Historical Collection, some of which are featured on our Rabbits in Australia site.

For Mikey, the rug summoned memories of his grandfather, a furrier who, after he left the trade, kept piles of unused pelts in his garage.

For me, it brought back memories of childhood holidays on a station in the New South Wales Snowy Mountains. Rabbiting was a twice-daily daily ritual for the property’s owners, and my brother and I would go out with them whenever we could. I remember a slow procession around the paddocks in the old ute, checking the set traps, and my surprise when an apparently lifeless rabbit, caught by the leg, would explode into leaping and scrabbling as we got near. I remember the small, strange crack as the rabbit’s neck was broken. I remember struggling to squeeze open the steel trap, and the farmer’s big brown hands delicately arranging the dirt around its gaping jaws.

There’s a photo Mum took of us on our return home.

I seem very proud to be wielding the ‘setter’. My brother is holding up one of the bleached bones we often brought back from the paddocks – sheep, cow, and kangaroo skulls, vertebrae and ribs that we occasionally convinced our parents to take home as souvenirs. For a kid living near Sydney’s lengthening fringe who’d never seen a furry animal killed before, there was lots of time to ponder life and death while bumping around in the back of the ute with the piles of bones, the loose traps rattling and the warm, bloodied rabbit bodies lolling.

Perhaps that’s why, when Mikey asked me what I felt when I saw the rug, my first reaction was: ‘I think about the 70 rabbits that died to make it’. When you look closely, each of the pelts has its own unique pattern of black, white, fawn and brown – a reminder of the individuality within even a plague population.

Of course the sheer number of pelts immediately evokes the vast numbers of rabbits living in Australia when the rug was made: an estimated 600 million by the 1940s. It had been the fastest spread ever recorded for a mammal anywhere in the world, erupting from a few small, scattered feral populations and the dozen rabbits released by Thomas Austin, landowner and member of the Victorian Acclimatisation Society, on his property ‘Barwon Park’, near Winchelsea in Victoria, in 1859. Austin’s action was the ‘defining moment’ explored in the film.

At the time, Austin commented that “[t]he introduction of a few rabbits could do little harm and might provide a touch of home, in addition to a spot of hunting.” Unfortunately, the rabbits did do much harm. Their impact on rural economies and diverse ecological communities was catastrophic. And so, hard on the heels of reflecting on the life of each singular skinned creature, while trying to grasp the scale and progress of vast swarms of them, comes the larger loss of biological diversity, soil and landforms, and the added impacts of feral cats, dogs and foxes, who surfed the rabbit wave into new niches all around Australia.

Even on this one property, the damage was everywhere: wide patches of bare earth, and dusty mounds with burrow holes that looked like a giant had poked his fingers into the ground and flung fistfuls of dirt to the wind.

The rabbits we trapped were skinned, and their pelts sent to town to be sold – by the 1970s, probably not for rugs, but for fur to make hats. The rabbits’ bodies went to feed the working dogs.

Collection objects are incredible touchstones. As Mikey and I talked, the rug connected my wide-eyed experience of trapping with Austin’s genteel ‘spot of hunting’, and the rabbits of Ilford and the Snowies with those set free near Geelong more than 155 years ago.

The film Mikey and the crew made should be on the Defining Moments website in the coming months.

What are your rabbit stories? Tell us in the comments box below, or at the Rabbits in Australia site.