A tale of extremes

There are few substances on the planet more changeable than water. As ice, water, and gas, water impacts almost every aspect of our lives. This blog post looks at places in Australia which have very distinct climates because of water’s ability to change form, from gas, to water, to ice. In particular, it looks at places where the extremes are reached. Welcome to the watery edge.

Driest (water as gas)

The National Museum has plenty of objects that relate to protecting oneself from the rigours of the natural environment. Among the most eccentric is the ‘Hollow Log’. It is a converted water tank which belonged to John and Roma Dulhunty, who undertook ground breaking research on Lake Eyre in the 1970s.

The tank is depicted in Roma’s second book, When the Dead Heart Beats Lake Eyre Lives, which focused on their experiences in 1973 and 1974. It is shown sitting on the flat bed of a four wheel drive vehicle, which given the difficulty of the terrain, this would have been the only way of getting a ‘caravan’ in.

The water tank converted to accommodation was an innovation to make the difficult life in pursuit of their research more comfortable and secure. In her description of it in When the Dead Heart Beats (p. 212) she outlines the needs the tank needed to fulfil. Headroom was an important factor, as was the ability not to be swamped or damaged in the fierce storms that are characteristics of Lake Eyre. The interior is fitted out much as one would expect from a normal holiday caravan, with twin beds at one end and simple cooking facilities near the door. It also had to be dust and insect proof. For example, at one point Roma mentions the plague of midges that sprung up during the 1974 flood. Eating and cooking had to happen inside their shelter to protect both themselves and the food.

Some small domestic items were left inside the tank, illustrating the social aspects of life while undertaking research in such a difficult environment. Onion skins were found. A long keeping and flavoursome vegetable, Roma used onions extensively to liven up their diet of largely tinned or dried food. On the whole, however, details of the camp ‘fixtures’ receive very little attention in the books. Most attention is placed on their relations with nearby Muloorina Station who gave the Dulhunty’s considerable support, on the exploration work and on the practicalities of undertaking the work. This included how to get around on the treacherous lake surface and, and the extremes of climate. Roma makes no comment on the sweet irony of converting a water tank to live in in the driest part of the nation.

Lake Eyre lies in the far north of South Australia. With an average rainfall of 127 mm per year, it is the driest, lowest and probably the most barren part of continental Australia. It drains 1.3 million square kilometres of the country, and has only rarely flooded to capacity.

The Lake is fed by the Diamantina, the Finke and the Georgina Rivers, and by Cooper Creek, famous for being the location where Burke and Wills died. All these rivers are highly ephemeral. The Lake Eyre Basin is one of the last unregulated river systems and as such as has considerable significance as an example of an ecosystem totally adapted to the intermittent presence of water.

Lake Eyre was named for Edward John Eyre, the first white explorer to sight it. In late 2013, the South Australian government honoured the request of the Arabana people to recognise its traditional name. The National Park is now the Kati-Thanda Lake Eyre National Park. Charles Sturt explored through parts of the Lake Eyre Basin through 1844 and 1845. The Australian Dictionary of Biography described Sturt as ‘a careful and accurate observer and an intelligent interpreter of what he saw, and it was unfortunate that much of his work revealed nothing but desolation.’ The emphasis on the extreme dryness was further highlighted when John Gregory published The Dead Heart of Australia in 1906, recounting his field trip there with University of Melbourne students in 1901-2.

Until John and Roma Dulhunty began their program of scientific research, knowledge of Lake Eyre was limited. This was not due to lack of interest, but the dangerous terrain. John and Roma’s first trip was in 1972 and they returned every year until 1978. They had the good fortune to be there in both dry and wet times. The first book written by Roma Dulhunty chronicled their first year in 1972 when rainfall was only marginally above the average of 127 mm per year. The following year rainfall was more generous and Lake Eyre was partially filled. In 1974, the lake flooded completely, and was the largest flood for approximately 500 years. This represented the most consistent and engaged attention by Europeans that Lake Eyre had ever received. John, a geologist at the University of Sydney, had been working for years on the Great Artesian Basin. Investigating Lake Eyre was the natural extension of his previous research interests. The main scientific significance of John Dulhunty’s geological work lay in the realisation that Lake Eyre serves as a continental rain gauge, with Australia’s climatic history recorded in its sediments. John’s work, along with that of other researchers, has enabled an unravelling of much of the continent’s climatic history over the last 250 000 years.

Wettest (water as liquid)

Humidity is the term used to indicate how much water vapour is in the air. At Lake Eyre, it is extremely low because of the low amount of rainfall and the high amount of sunshine. The place on the Australian continent that is the opposite to Lake Eyre is wet tropics of far north Queensland. The wet tropics region, from Cooktown to Tully, is the wettest region in Australia. Three local towns have a friendly rivalry for the golden gumboot award, the town with the highest annual rainfall. The most recent winner is Tully, but the towns of Babinda, and Innisfail have also been winners in the past.

Innisfail’s average rainfall is 3569.5 mm while the highest recorded was 5894.9 mm. Tully receives an average of 4116.2 mm and its highest recorded rainfall was 7898.0 mm. Babinda average is 4279.9 mm and the highest was 7040.2 mm in 2010. Speaking in averages, Babinda is the wettest place but as rainfall can still vary a great deal annually, the golden gumboot can be won by any of the three. So, Babinda receives on average thirty three times the amount of rain than Lake Eyre. As you can see from the photo of Babinda Creek below, the area is lush, green and very beautiful. Locals frequently talk about how refreshing it is to swim in places like this.

Take a peek at the downside to lots of rainfall.

The Museum has collections which relate to settlement and industry in the wet tropics and the attempts to preserve the rainforest in later decades. The object selected here is a timber cart, part of the Rankine Family collection relating to their timber mill at Yungaburra, just behind Cairns on the Atherton Tablelands.

This high sided, iron wheeled cart was used to transport timber within the mill. Once cut into manageable sizes the sawn timber was loaded onto carts ready for drying. Mill employees moved the loaded timber carts between the milling sheds and the drying kilns. Of particular note is the amount of moss, mould and lichen growing on the wood, so characteristic of the fate of organic objects in high rainfall areas. Wet, moist conditions do not lend themselves to object preservation.

This mill was one of many on the tablelands supplying timber to fuel the rapid growth of towns further south, especially Brisbane, now that forests closer to the main urban centres and along the coast had been depleted. In the later decades of its operation, it diversified into timber veneers, and supplied substantial amounts of timber to the armed forces. The mills were a backbone of local employment for decades, an argument which was frequently used in the fight against conservation. The mills closed when world heritage listing was achieved in 1988.

The very high rainfall supports a very unique forested ecosystem, which was listed as a World Heritage area on 7 December 1988. According to the Wet Tropics Management Authority, ‘Compared with other tropical rainforests of the world, the wetter parts of the region lie at the extremely wet end of the hydrological spectrum.’ The high rainfall and resulting abundance of plant and animal growth supported a thriving indigenous community for many thousands of years. The abundance in the wet tropics environment made this area one of the most heavily populated before the arrival of Europeans, with eighteen different cultural groups.

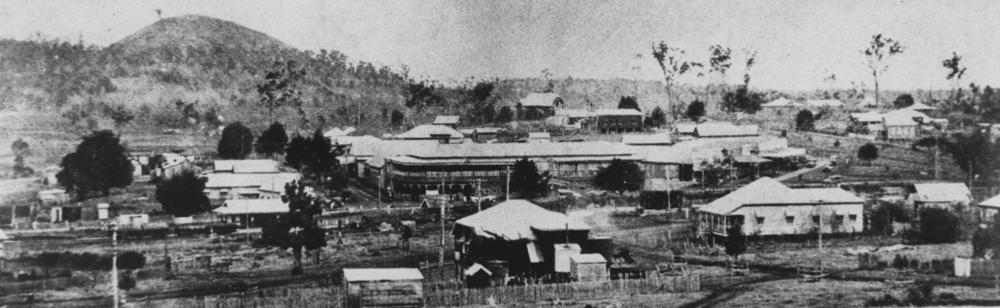

White settlement of the wet tropics area did not proceed in a particularly orderly way, marked by rivalry between fledgling settlements all the way from Cooktown in the north to Tully in the south. The Palmer River gold rush in 1873-4 lead to the establishment of Cooktown on the Endeavour River as way of getting supplies to the diggings. Christie Palmerston, for whom the Palmerston Highway was named, found many years of employment cutting tracks between the inland settlements on the tablelands and the coast. One of his tracks established Port Douglas, and linked it to the tin fields at Herberton. Exploration reports by George Dalrymple helped to draw attention to the settlement potential of Trinity Bay, the future site of Cairns. Further gold discoveries on the Atherton tablelands led the Queensland government to decide to establish Cairns formally. The later construction of the Cairns to Herberton railway attracted many migrants demanding lands to be opened up along its route. Along its route was Yungaburra. Initially an overnight stop en route to the mine fields, Yungaburra was surveyed in 1886, but the majority of settlers arrived after 1891. Forty acre blocks had been carved out of the rainforest, which they set to clearing. The photograph below illustrates how successful they were at the task.

Yungaburra remains one of the more intact streetscapes of far north Queensland, illustrating the uses to which all the local timber was put.

The abundance and diversity of plants that is the characteristic of the wet tropics now underpins its thriving tourism industry. According to Tourism Queensland, in the year ending June 2013, more than 2 million people visited northern Queensland. Of that number, around 1.5 million went for a holiday, proving that high rainfall makes for a better visitor attraction.

Iciest (water as a solid)

Given that Australia is generally known domestically and internationally as hot and dry, many would be surprised to learn that that the lowest temperature ever recorded on the planet is on Australian territory. Just not somewhere where anyone is likely to go. It was the Australian Antarctic Territory, and the temperature was minus 89.2°C.

In contrast, the lowest recorded temperature on the Australian mainland is minus 23.0°C at Charlotte Pass in the Australian Alps on 29 June, 1994. The nearest major settlement to Charlotte Pass is Cooma, which is well known in Australian history for its role as the centre of the Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Scheme. Tasmania is positively tropical in comparison, with its lowest ever temperature recorded at Shannon on the 30 June, 1983. It was minus 13°C.

The object from the collection chosen to illustrate the solid nature of water are skis, specifically skis belonging to an Antarctic dog sled. These are part of the George and Robert Dovers collection, which consists of skis and other items used by father and son during various Antarctic expeditions. George Harris Sarjeant Dovers (1887-1971) was a member of Mawson’s expedition in 1913, while his son Robert George Dovers (1922-1981) participated in two later Antarctic expeditions; the first to Adelie Land in 1951-52 and then to the Antarctic continent to establish the new Mawson Station in 1953-55.

George was the cartographer, a role which was vital to the success of the expedition. He was part of the group that established the western base at Queen Mary Land in February 1912. Voyages of exploration are mute unless the knowledge acquired is accurately mapped, and made available to a wider audience. This mapping could not have taken place without the use of dog sled teams. Robert, being a surveyor, continued in a similar vein to his father.

Skis in the Antarctic were much more than just items for recreation. They were essential equipment for any member of the expedition. The Museum’s dog sled skis transported their food, shelter and scientific equipment. Dover’s group on the western base had nine dogs. The Western Base replicated many of the experiments undertaken at the main base and also included observations of the Aurora Australis. Sledging was dangerous work, as the death of Lieutenant Ninnis on 14 December 1912 showed. He, the entire sledge and dog team fell into a crevasse and could not be recovered. The world of solid water can be as challenging and dangerous as the world of gaseous water.

Mawson’s expedition greatly expanded scientific knowledge of the Antarctic region, and the expedition attracted enormous press coverage. The many stunning images produced by the now well known expedition photographer, Frank Hurley, undoubtedly helped to cement this new appreciation of the beauty and terrors of ice in the public mind. The anniversary of Mawson’s expedition has recently been celebrated with a wide variety of activities including a re-enactment voyage, a website and various publications.

More

This blog post is the third essay in my series on the history and culture of water in Australia. Read my fourth essay, ‘Helpful to harmful‘.

Links

Wet Tropics Management Authority website

Tom Griffiths’ talk on ABC Radio National’s Science Show, on the centenary of the Mawson expedition (address to the Australian Academy of Science)

100 years of Australian Antarctic expeditions website

References

Dulhunty, Roma, The Spell of Lake Eyre, Lowden Publishing Co, Kilmore, 1975.

Dulhunty, Roma, When the dead heart beats Lake Eyre lives, Lowden Publishing Co, Kilmore, 1979.

Dulhunty, Roma, The rumbling silence of Lake Eyre, the author, Seaforth, 1986.

Top image: Detail of the Trevi Fountain, Rome, Wikimedia Commons.