Introduced to native

The history of water includes the history of gardening. Different species have different water needs, reflecting their place of evolution. When European settlers arrived in Australia full of images of lush meadows and verdant trees, based on their lived experience in many cases, a kind of cognitive dissonance happened. The old environmental reality and their new reality didn’t match up. This gap has been slowly closing over time, and we can see this in action through the history of gardening. These objects, gardening books and pamphlets, chart a transition in thinking about vegetation and water in Australia.

The first group of books come from the library of a wealthy pastoral family, the Faithfulls of Springfield. Springfield evolved from a 518-hectare land grant acquired by William Pitt Faithfull in 1828 up to 3183 hectares, with ownership remaining in the one family. William Pitt Faithfull established the Springfield merino stud in 1838 with ten rams selected from the Macarthur Camden Park stud. The stud evolved slowly over the years until the early 1950s when, under the management of Jim Maple-Brown, a scientific approach to wool-growing was adopted.

According to William’s entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Springfield homestead was built in the early 1840s, and by 1858 its garden was well known for its ‘English flowers of every shade in perfection’. The garden was Mary Faithfull’s passion. This interest in the garden was transmitted down to the couple’s children. How else would her son come to exhibit 100 chrysanthemums at Goulburn’s first chrysanthemum show in 1890? Two years later, their daughter won second prize for her showing of roses and stocks.

Mary ordered the majority of her seeds and plants from England each year. It’s very likely that these English garden books helped her to make selections, although catalogues from nurseries were also vital. Sadly, no catalogues are in the Springfield collection, but the books that the Museum holds include some of the best known garden books of the nineteenth century.

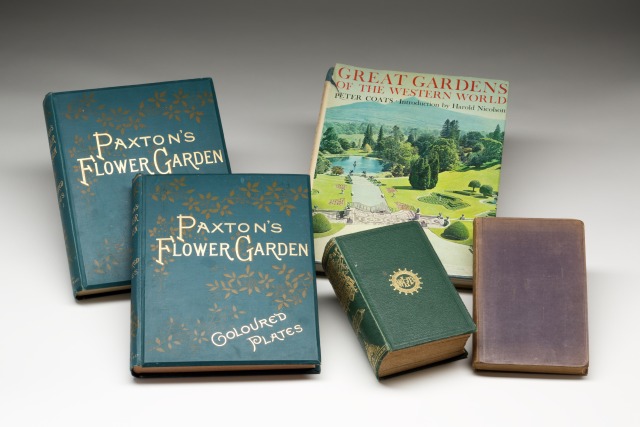

The English Gardener by William Cobbett was first published in 1829 and ran to multiple editions. The Faithfulls had the 1838 edition and it belonged to Miss CM Faithfull. The other very well known books were Paxton’s Flower Garden, and Beeton’s Book of Garden Management. Paxton ran to three volumes, and the Faithfull family had volumes one and two. Cobbett and Beeton’s books are large, closely printed books conveying advice in great detail on garden design, layout, management and cultivation.

On Christmas Eve, 1881, The Goulburn Evening Penny Post published an extensive description of Springfield. If we compare this to the contents pages of Beeton and Cobbett, we see almost complete congruence. Hedges, a shrubbery and lawn, gravel walks, a greenhouse, there’s even a fish pond. Similarly the plant selection could easily be a list drawn from either author. In the shrubbery were Portugal and English laurels, chestnut, walnut, hazel, junipers, berberris, and holly. Flowering plants included carnations, verbenas, phloxes, antirhiniums, fox gloves, petunias, peonies and of course, ‘gay’ roses. Extensive development of the property’s water resources had occurred to enable all this horticultural effort. There are only two native species mentioned, the kurrajong which was planted in the shrubbery, while acacia was relegated to acting as a windbreak.

Later visiting journalists noted how immensely English Springfield was. A very long article in the Town and Country Journal from 1905 went into great depth on the breeding program at Springfield for sheep and horses, the distribution of water from the Mulwaree River, and went on to remark that ‘The old home, now the residence of Miss Faithfull, is a delightful, old-fashioned house, surrounded by finely-wooded grounds, and with nice gardens, studded with choice shrubs, and bright, in the spring time with a profusion of flowers. A part of the brick walls of the building is ivy clad, and altogether it presents a truly old-world appearance’.

The same imagery still applied in 1933, when The Farmer and Settler described Springfield. ‘There are two homesteads on the estate, one, the original residence, now occupied by Miss Faithfull, and the other, Mr. A. Lucian Faithfull’s home, built over forty years ago. The whole estate resembles an old-world park. The home steads are surrounded by belts of beautiful pines that defy the sweeping winds of the tablelands, and there is a delightful garden, seven acres in area, crowded with marvellous flowers, fruit trees, shrubs and evergreens.’

Springfield’s garden represents an immense amount work and devotion by generations of the Faithfull family. If you read their gardening books, you can’t help but feel exhausted by the amount of digging that is recommended, although how much they themselves laboured is not immediately clear. (It is difficult to imagine corseted ladies trenching to three and half a feet, as recommended by Cobbett.) In some reports of the agricultural or horticultural shows, the gardener is listed in brackets as an addition to the family member.

Springfield also represented an almost complete substitution of native plants, used to variable water availability, with exotic and highly water dependent species. Reading Paxton gives some insight into the mentality behind this. Joseph Paxton was the head gardener at Chatsworth House, in the Peak District in Derbyshire. His books were intended for wealthy gardeners who could maintain greenhouses and gardening staff to cosset exotic imports. Included in the volumes held by the Faithfulls were images of Australia flora, such as these plates from Paxton.

These were presented simply as another exotic that you could furnish your greenhouse with. Exoticness and unusualness were the key goals that marked one out as a gardener of taste and distinction. The preface to volume one of Paxton said that the book was intended as a tool for growers ‘to ascertain the real Horticultural value of the numberless so called varieties with which the lists of dealers are crowded.’ Volume two included plants from thirty seven different parts of the globe, a clear indication of the links between horticulture and imperial expansion of the nineteenth century.

Springfield was exactly the specimen based, exotic kind of garden that Jean Galbraith spent her life trying to educate people away from. Our second group of gardening materials were part of her own library, and are a marked contrast to the Springfield books. These are simple pamphlets, compared to the highly polished Springfield books, all focused on growing or appreciating native plants and written to appeal to anyone.

Jean Galbraith was one of the most popular garden writers in twentieth century Australia. She commenced writing ‘for money’ when she was a child, regularly winning the newspaper children’s page best letter for which she was thrilled to receive two shillings and sixpence.

Jean’s grandparents arrived in Gippsland in 1878 from Beechworth, a mining town. They found the moral atmosphere of Beechworth, with its forty two hotels, an undesirable place to raise their growing family. The family ran a dairy enterprise, primarily making cheese. They lived on the ‘wrong side of the river’ and too far away from a good bridge to sell the more perishable cream and milk. Jean’s father took an eleven acre parcel of land instead of money as his inheritance, and continued to live on the farm. Most of the family had an interest in gardening and the natural world. Her education was disrupted due to illness, but this clearly did not stop her passionate interest in the world around her.

Jean lived her whole life in the family home, near Tyers in Gippsland. Her first writings for the new Australian gardening magazine The Garden Lover, starting in 1926, featured her local landscape, and she wrote consistently about this for ten years. She was friends with McDonald of the Argus, who regularly mentioned her in his column. After that, the garden her family established there, and which she looked after until ill health forced her move to a nursing home, became the focus of the column. Highlights from that column were collected together in a book called Garden in a Valley published in 1939, and reprinted in 1985. Garden in a Valley established Jean’s reputation as a gardener and botanist amongst the broader Australian public.

Botany requires attention to detail; an eye for both what is general and what is particular about the plant in question. The Museum holds her microscope, a custom made gift to her from friends in the Field Naturalist’s Club during the 1950s. The wooden mount was modified so she could fit it in a suitcase for travelling, such as her trip to Western Australia in 1964. She also had a folding magnifying glass, a gift from the son of her mentor, Mr HB Williamson. Microscopes enabled many advances across multiple fields of science, including botany and medicine.

Jean always tried wherever possible to see the plants she was writing about. This entailed lots of travel, usually facilitated by friends or by public transport given that Jean never learnt to drive. Her early forays were based on local trips around the family farm. She would pick quantities of wildflowers and take them to Melbourne to participate in wildflower shows. As one of the founders of the local branch of the Field Naturalist’s club, she participated in many local trips. As her reputation grew, she was asked to take on increasingly bigger projects culminating in the Field Guide to the Wildflowers of South Australia. Jean donated to the National Museum some of the camping gear that she used on her field trips, including her sleeping bag, water bottle, and cooking equipment.

Her writings about native plants, especially in the early years, consistently emphasised their beauty and delicacy. For example, she described the Satin Everlasting or Helichrysum leucopsidium as ‘a stretch of silken embroidery, flecked with pink, frilled with rose’. In the same article, she mentions the ‘creamy foam’ along riversides and hollows, the flowers of sweet bursaria (The Garden Lover, Feb, 1926, p. 380). Given her location in Gippsland, among the wetter locations of Victoria, it is not surprising that Jean regularly talked about riverside or marsh plants in her early writings. In April 1926 she wrote evocatively of Epacris microphylla or coral heath.

‘Never was a flower more truly named’, she said, ‘the white waxy bells so short as to be almost cups, crowd like coral over the bushy plants, a gleam of fairyland on earth’. The May 1926 edition focussed on highly water dependent ferns found high in the Gippsland hills. Some columns were simply accounts of bush walks and what beauties she found. In January 1927 she said:

…to know their full beauty, visit the stream sides, where they grow in mingled luxuriances of leaf and flower; where tree ferns mix with gums and maiden-hair brushes the water; where shy brown lyre-birds may still be seen by quiet watchers, and the silver air is tangled in mutable loveliness of scent and song.

She gave instructions on how to lift, transport, and grow on the native plants she discussed in her column, encouraging gardeners who might otherwise have stuck to more familiar introduced species to get to know the diversity of indigenous plants. She also fostered an appreciation of their diversity and their suitability to the different climates, and therefore water availability, that gardeners found themselves in. While she rarely speaks about watering, other writers in The Garden Lover regularly talked about it in regard to the roses, phlox, or other introduced species which they were advocating.

As her writing evolved, her message became increasingly about conservation. In her preface to Wildflowers of Victoria she combined both these messages:

The robe of the countryside is there for you to enjoy. It is a green robe, worked in bright colours that change from month to month and from place to place: embroidered with white and lilac in the gullies and bright colors on the hills; sown with jewels in the grassland, and flung in crumpled folds of white daisies for a thousand acres in the Mallee. The only rents in it are those we have made. Perhaps more of its beauty might remain if, years ago, we had realised how easily it is destroyed.

More

This blog post is the first essay in my series on the history and culture of water in Australia. Read my second essay, ‘Domestic to industrial’.

I find this very interesting as I’m currently working with an old established country garden, mostly on English lines, and incorporating where I can things that are native. It originally included a wide variety of fruit trees, and I’m maintaining and extending that. It’s often easier to make new areas of native plantings that to combine with the exotics, because of the difference in watering needs. On what was originally the back side of the house, though, there are magnificent blakely’s red gums, still with the chain for tying your horse hanging from the trunks. If you look at what’s available in plant nurseries, however, it’s still mostly non-native plants.