Discoveries in January

As January makes way for February, I take a moment to reflect on my first month as an artist-in-residence at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra.

It has been a fascinating journey so far, understanding how the Museum functions, what motivates the people that work there, and exploring what is the role that a Museum can play. I have been encountering the endless stories that are contained within the entire National Historical Collection and thinking about how I might go about traversing some of these things during my time here.

A reoccurring driver in a number of my past projects has been memory. For example, in 2012 I presented a project called ‘Roadside Frequencies’. This project was held in a paddock by the side of the Sturt Highway between Narrandera and Wagga in the Riverina region of New South Wales.

It was a performance for unsuspecting traffic in which dancer Victoria Hunt (see photograph above) was perched on the wall of one farm dam, and I was on the other bank. I had installed an upright piano which was delivered there on the back of a ute by local farmers Garth and Graham Strong. My piano was mic’d up and attached to a high powered radio transmitter which hijacked the radios of passing cars. An interruption to a long trip, a tiny anomaly in a repeating landscape, a hiccup in a deep breath.

Victoria and I improvised for over an hour for a large audience of passersby who all stopped, took photos, beeped their horn or yelled out of their windows enthusiastically.

This project was about creating an installation using music and dance, but more importantly it was about memory. In a landscape that is being reduced to large-scale industrialised agricultural process which remove people from the land, this project was an opportunity to create new memories involving people out in the landscape.

The hope was that for people who came across this performance, this large paddock may now in some way, hold something more than the memory of it being a practical commodity, a factory floor, but also, something that holds the story of people, even inexplicable ones involving a piano and a dancer.

To view a film about the performance, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RdETbmL09Mk&feature=youtu.be

Memory theorists are broadly based in two camps. They argue about whether memory is relational or absolute. The relational side believe that memory ‘stores information about the relationships between objects and ideas, but not necessarily details about the objects themselves’. They believe that we construct a ‘representation of reality’ out of these known relations. The competing theory, or the Record Keeping Theory, argues that the memory is like a recorder, notating most of our experiences accurately.

As there is evidence to support both arguments, I like to take a non-binary viewpoint and explore, through my arts practice, the intriguing aspects of both theories.

By tapping into the known record keeping part of memory as well as exploring the relational side, I am able to marry fact with emotion with some space left over for dreaming. Dreaming about what it all might mean, or dreaming of new interpretations.

And in the case of my time at the Museum, how do I take all of this information that I uncover, both factual and emotional, and decipher it into something that includes my interpretation, my viewpoint, my DNA. And is that even warranted or ethical?

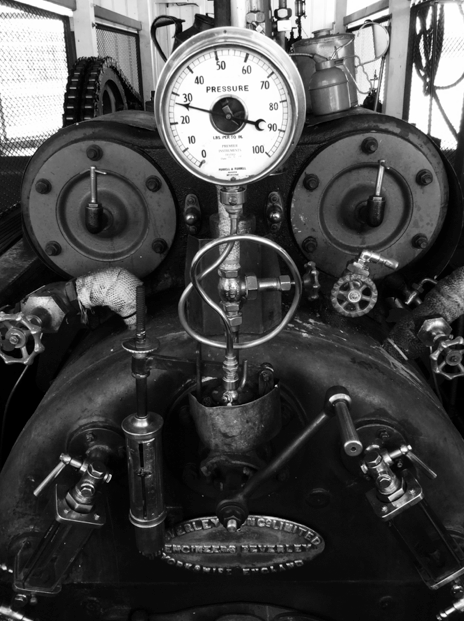

I have spent a great amount of time on the Paddle Steamer Enterprise during January. Looking through the Museum collection at relevant items from the vessel. Reading documents, letters and postcards from its time on the river system. I have been fascinated by the many different stories and roles that the Enterprise has fulfilled as an explorer, a shop, a tourist attraction, a hero during environmental disasters.

However, it is the role as a home that is intriguing me at the moment. The stories of the Creager family raising two children on board, their possessions and memories. The mother, Hilda, sewing pajamas on board the boat with her old Singer sewing machine to send to soldiers during World War One. The father finding an old beat up fishing basket and refashioning it into a babies bassinet. The kids inventing games to while away the hours on the boat, and the daughter Jocelyn talking about when the family eventually moved onto land in Mildura, how she had trouble sleeping at night without the gentle rocking of the boat (and how the new owners of the boat immediately installed stabilisers so the boat no longer gently rocked in that manner, so it was more like a building on land).

Hilda Creager was one of only a very small number of women who had their own fishing license, which is of real poignancy at the moment, as in 2015 we are celebrating both the 40th anniversary of International Women’s Day and also thinking about the role of women during this centenary of World War One.

Working with the volunteers who maintain the Enterprise at the National Museum lets me connect first hand to the vessel’s current life. The Enterprise is maintained by a group of retired men with various practical skills, knowledge and enthusiasm who are working with the Museum to keep this boat alive.

I have spent time on board preparing for my performance on February the 28th, see:

http://www.nma.gov.au/whats-on/events/by_the_water_2015

In preparation, I have been placing contact microphones onto the boat, tapping it, playing it with a violin bow.

The Enterprise has many nostalgic sounds, such as the steam whistle:

But I am also searching for something more, for ways in which to unlock the sound within the structure, to enable tones to be heard that hold the weight of time in their timbre, their pitch, and to create a melody and rhythm that isn’t part of record keeping fact, but is an extension of representational memory making, an extension of the boat’s own history, its current life and its intersection with me.

http://youtu.be/oEBf2dF0qv8

Anatomy Collection

In my initial tour of the Museum collection, in one of the repositories, I was shown part of the Australian Institute of Anatomy collection of comparative anatomy. Thousands of human and animal specimens preserved in jars that were once a part of the Australian Institute of Anatomy, and which now reside in the collection at the National Museum.

On this visit I didn’t have the opportunity to see the human specimens. However, when viewing the animal specimens I had a strong sense of connection, of there being something human about them. Interest in how species relate to each other is one of the areas of interest of Senior Curator Kirsten Wehner and it was fascinating to spend some time talking to her about her interest in the collection.

My experiences when viewing the collection were :

* The “special feeling” that I was looking at something taboo;

* Having not eaten meat for 25 years, I see a connection between humans and animals as living things, so my connection to animal species in a jar could still relate to them as living beings;

* My fascination with a living form being reduced to a specimen and seeing this as some sort of metaphor for a futility of life, government policy, environmental and community management;

* That feeling of “more”. I want to see more and be pushed further, not quite squirmy, not quite scary, but fascinating;

* The beauty of being able to look at for example, an echidna’s brain, which in a jar looks much like I would image a shrunken human brain to look;

* My fascination with there being specimens of “War Wounds” and “Abnormalities”;

I discussed my encounter with the specimens with artist Duke Albada and she talked about travelling overseas and seeing as tourist attractions the corpses of world leaders or important historical figures, and that although masses of time has passed, and you have paid an entry fee, and are potentially in a long queue, you can still sense the human in the specimen in the jar.

I am looking forward to revisiting the collection, talking more to Kirsten about her thoughts and research, and wondering about what links their are between my interest in Arts/Health and a collection of comparative anatomy.

For now, I am happy photographing the specimens and giving them human titles.

Here is #1 in the series:

I Love You, Your Brains Are Delicious.

By coincidence, the day of my meeting with Kirsten to discuss the comparative anatomy collection, I spent the morning at the ‘In The Flesh’ exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, with the works of Piccinini, Mueck, and others.

What an exhibition, these life-like sculptures which convey so much emotion as well as so much realistic representation. I’m sure I saw them twitch, and I’m sure one of the sculptures was my grandmother. It looked at me in that certain way.

Finally during January, I have had discussions about the role of the Museum. As a research facility, a keeping place, an events venue. Should it be driven by research, audience numbers, or some other criteria?

The same discussion happens in the arts. Do you place more value in audience numbers than experimentation? If arts funding is aligned with audience numbers then is that to the detriment of experimentation and risk taking or the creation of difficult artworks?

These questions exist in many sectors across various institutions. How do we get this balance right? In the case of the Museum, how to balance the necessary research that can be gleaned from the past and present? What role can the Museum play in placing alternatives, options and research at the forefront of a visitor experience and the national debate? How can our national institutions contribute to worldwide conversations about our future thorough rigorous analysis, and how can this be done in a way that engage not just an academic audience, but the general public?

Fascinating stuff, I’m looking forward to February.

I enjoyed this blog post, Vic. As a teacher of Visual Arts in a ‘previous life’, I find your observations upon the nexus of thought/expression/creativity to be most compelling. Your aural/physical investigation of the PS Enterprise has much potential, particularly in unlocking its stories in a way which relies not only upon physical resonance, but also the resonance of memory and experience. I look forward to hearing how the Enterprise shares its ‘memories’ via the metaphysical encoding of its structure and its ‘iron heart’.

I think the NMA has a really important role to play in shaping how Australians and visitors see the world around us. It’s important to put things in context, involve the community in an active way, bring things to people who can’t necessarily be physically there (through an online presence). I think this century will really see museums coming into their full potential.

Thanks for your comment about the community-oriented role museums can have in these difficult times, which reminded me of an observation made by Naomi Klein in her recent book about climate change, This Changes Everything: ‘What if part of the reason so many of us have failed to act is not because we are too selfish to care about an abstract or seemingly far-off problem–but because we are utterly overwhelmed by how much we do care? And what if we stay silent not out of acquiesence but in part because we lack the collective spaces in which to confront the raw terror of ecocide? The end of the world as we know it, after all, is not something anyone should have to face on their own.’ I reckon that museums can and should be acting as collective spaces, enabling people to make sense of climate change and related challenges, and to deal with the emotional and cultural dimensions of these issues. Robert Janes speaks powerfully about this moral responsibility of museums here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d7PT_Ew0hhE