‘Southern Cross’ lands in Honolulu: Crossing the Pacific

At 12:17 pm on 1 June 1928, the ‘Southern Cross’ landed safely at Wheelers Field, Honolulu, with her crew – Charles Ulm, Charles Kingsford Smith, Harry Lyon and James Warner. They received a warm welcome and shared a sense of relief in completing only the fifth successful aerial crossing from California to Hawaii. Celebrations were short-lived as they prepared for the next leg of their journey across the Pacific Ocean.

Two objects celebrating the flights of Charles Ulm are now on display in the National Museum’s new acquisitions showcase. This is the first in a series of blog posts to come during June, remembering Ulm’s flights above oceans and continents from 1927 to 1934.

The ocean

During the 1920s, crossing the Pacific Ocean by air was a challenging and dangerous prospect, and for many people it seemed impossible. The world’s largest body of water, the Pacific Ocean is prone to strong winds and currents, and serious levels of turbulence. While the ocean contains many islands, most are located near the equator, meaning that reaching suitable places to land for refueling, or in emergencies, was difficult.

Charles Ulm had returned to Australia from the First World War, keen to fly and pursue his interests in commercial aviation. Ulm’s dream was to cross the Pacific Ocean, a dream also held by Charles Kingsford Smith, and the two men formed a partnership in 1927 hoping to pool their resources and find financial backing for the venture. After seeing that Charles Lindbergh had flown solo non-stop from New York to Paris, across the Atlantic Ocean in May 1927, Ulm and Kingsford Smith felt confident that they could push forward with their ambitions. Few people, however, showed real interest in something that seemed so risky.

In June 1927, Ulm and Kingsford Smith flew around Australia in an effort to prove that air travel was safe, and the feat of crossing the Pacific Ocean was possible. The distance around the continent, about 12,000 km, was similar to that across the Pacific. They completed the flight in 10 days, five hours and 30 minutes – less than half the previous record set by Captain EJ Jones and Colonel H Brinsmead in 1924. That same month, US Army lieutenants Hegenberger and Maitland made the first successful flight from California to Hawaii in the ‘Bird of Paradise’.

Ulm and Kingsford Smith’s achievement had the desired response. Encouraged by the congratulations showered upon them, they announced their plans to fly across the Pacific Ocean at a luncheon in Sydney, held by Sun Newspapers Ltd in their honour. As they asked Sydney’s leading businessmen and the public for their support, New South Wales Premier Jack Lang announced that his government would give Ulm and Kingsford Smith £3,500 for their trans-Pacific flight.

The men wasted no time, boarding the S.S. Tahiti on 14 July to sail for California. Ulm had married his fiancée, Mary Callaghan, on 29 June, leaving without a honeymoon, but the promise of his return after flying across the Pacific Ocean. Ulm and Kingsford Smith were joined on board the Tahiti by Keith Anderson, who was to be co-pilot for the flight, and during their travel they received some navigation training from the vessel’s third officer, Harold Litchfield, who would join the aviators on some of their flights in later years.

The aircraft

In America, their first task was to acquire an aircraft suitable for the flight. After considering several single-engine aircraft similar to those used by Charles Lindbergh, the tragic loss of three aircraft and seven lives in the Dole Air Race to Hawaii made them reconsider their choice of aircraft and preparations for crossing the Pacific Ocean. The tragedies of the Dole air race, also cast doubt in the minds of the public and their potential supporters.

Australian explorer Sir George Hubert Wilkins, contacted Ulm and Kingsford Smith to offer them one of his two Fokker aircraft, which he had purchased, but found unsuitable for his Arctic expeditions. Wilkins agreed to supply an aircraft to Ulm and Kingsford Smith, on the understanding that full payment would be made prior to their flight. Later Wilkins wrote:

I noticed in the newspaper that three Australians had arrived in San Francisco on their way to purchase a Ryan airplane (as flown by Lindbergh) for a flight to Australia. I knew that the only machine in the world which had the capacity and range to carry three or four men over the distance non-stop which it would be necessary to cover on a Pacific flight, was the Fokker ‘Detroiter’ which I had at that time stored at Seattle. I immediately got in touch with Kingsford Smith and Ulm. [1]

Ulm and Kingsford Smith received a gift of £1,500 from businessman Sidney Myer, allowing them to secure the aircraft, a tri-motor Fokker, which they named ‘Southern Cross’ – something Australian, aerial and perhaps seeking some inspiration from the heavens above. The months that followed were filled with the work of adapting the aircraft and testing it for the journey ahead – the installation of three Wright Whirlwind J5C engines, six fuel tanks carrying a combined 1,298 American gallons, and the best available navigation and radio equipment.

The large fuel tank installed behind the pilot and co-pilot seats blocked their access to the cabin, with their only means of entering the cockpit being to climb in one of the side windows, as shown in this photograph of Ulm. Austin Byrne Collection, National Museum of Australia.

Their work with the aircraft continued to stretch and strain their finances. Ulm went from meeting to meeting attempting to secure further backing. The New South Wales government pressured the men to sell the aircraft, abandon the flight and return to Australia.

A chance meeting with Californian oil magnate Captain Allan Hancock offered the men some hope. Hancock invited Ulm and Kingsford Smith to join him on a twelve day cruise on his yacht, where he gave the men many valuable lessons in navigation and questioned them extensively about their flight plans. At the end of their trip, Hancock offered to buy the Southern Cross and cover the flight’s outstanding expenses.

The crew

Anderson had travelled to Hawaii inspecting suitable landing grounds and securing stores of supplies in readiness of the flight. As the financial pressures mounted, he returned to Australia, but when Hancock’s support had been secured, Anderson was unable to afford the trip back to California to join his friends. In Anderson’s absence, Ulm, who was originally to be navigator, took the position as co-pilot, for which by then he had sufficient experience. The aviators were also convinced that they should secure the services of a more experienced navigator and radio operator to ensure their success.

Radio operator James Warner and navigator Harry Lyon, who had both served with the US Navy during the First World War, joined the ‘Southern Cross’ crew a few weeks before their departure. Warner had not yet flown in an aircraft, but ably prepared the equipment, and after several test flights the men were able to work together – communicating via penciled messages passed between the cabin and cockpit via a stick, as they were unable to hear each other over the roar of the engines.

The flight

With all the preparations made, the ‘Southern Cross’ and crew were ready to depart. According to the aviators, it was their “aim to show the world that the Pacific could be spanned by air, not by any desperate struggling to land far from our fixed destination or by any eleventh hour snatching from disaster, but with a substantial margin of safety.” [2] On 31 May, at 8:54 am, they took off from Oakland Airport. Ulm kept a log book throughout their journey, and the following extracts from Ulm’s flight log help bring to light some of the challenges encountered on the first leg of their journey to Hawaii:

31 May 1928

- 9:06 am – Over Golden Gate, 1,100 feet. Hoisted Aussie flag.

- 10:10 am – Clouds banking up thickly ahead – look max. height of 2,000. As we pass clouds it is bumpy, and getting fairly cool.

- 1:12 pm – Ten minutes blind flying; clouds just seemed to blow right up. We opened up motors and climbed above them.

- 4:35 pm – Smithy and I worried re gas consumption. If our estimates of what is left in Wing Tanks is correct, we can’t make Honolulu.

- 6:07 pm – 9 hours 13 minutes out. Sun sinking quickly on starboard bow; very hazy ahead.

- 8:06 pm – Outboard wing tanks cut out.

- 11:36 pm – Ran into heavy clouds at 4,000. Rain and bumps. Blind flying.

1 June 1928

- 1.55 am – Clear sky, no clouds; good moon; a few stars; everything lovely.

- 2.33 am – Sighted steamer on port bow. Smithy signalled with searchlight while I flew ‘S.C.’.

- 8:56 am – Land sighted on port beam. Smithy and I shake.

- 9:17 am – All apparently mistaken. Only clouds; no land sighted yet.

- 10:56 am – Mauna Kea sighted!

- 11.06 am – Gliding down to get under fog surrounding Oahu.

- 12.17 pm – LANDED WHEELER FIELD. [3]

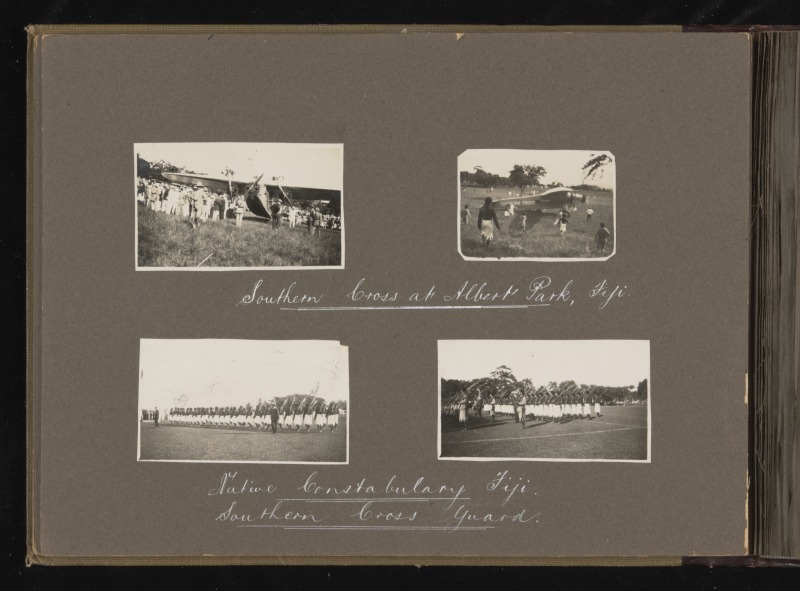

The crew rested the night in Honolulu, but were eager to get an early start the next day. They left Barking Sands, Kauai, at 5:22 am on 2 July and completed another gruelling day and night of continuous flying, reaching Albert Park, Suva, Fiji at 3:50 pm local time. The 5042 kilometre (3133 mile) journey was the longest continuous flight completed across water.

- 5:31 am – Smithy and self shake hands on successful take off on scheduled time.

- 6:52 am – Made first rough check on gas consumption. Believe same better than on previous hop. This due to our keeping lower altitude.

- 10:05 am – Warner reports radio equipment completely out of communication and that he is working on it.

- 11:45 am – Smithy flew around one storm. I flew around another. Now they seem to be closing in all round, so Smithy has controls again.

- 3:50 pm – Just as Smithy took over controls from me, the starboard motor started to cough. ‘Tis not a fault in the motor, but we are running on outboard wing tanks, and something is apparently wrong with the gasoline feed line.

- 7:50 pm – We probably lost an hour’s flying in those darned clouds, but we are out of them now, and gliding down to warmer climes.

- 11:33 pm – Lyon reports that we have just crossed the line (Equator).

- 6:30 am – Smithy estimates that we are out of luck, and will have to come down before Suva, as gas won’t last. Personally, I think we’ll just about make it O.K. if we are on course now.

- 10:10 am – Whoops of joy on board, for after trying every tank and breaking gasoline connections, Smithy and self decided to hand pump gas from main tank to gravity, and now we find we have seven hours’ gas left. We’ll make it now O.K. [4]

After their perilous and pioneering flights to Honolulu and Suva, the final leg of their journey seemed less challenging, but they were forced through treacherous conditions, with constant storms hammering the aircraft. Southern Cross and crew arrived at Eagle Farm, Brisbane, on 9 June 1928, having completed the 11,585 kilometre crossing in 83 hours, 38 minutes of flying time. The aviators were greeted by huge crowds of adoring fans in Brisbane and then at the official reception in Sydney on 10 June. The celebrations and following flights are the subject of the next blog post.

Postscript

Eighty-seven years after Ulm and Kingsford Smith piloted the ‘Southern Cross’ across the Pacific Ocean, their feat has now been eclipsed by regular jet air services that cross the expanse in only a fraction of the time taken on the first flight of 1928. Qantas A380 aircraft VH-OQG, named in honour of Charles Ulm, commenced service in 2010. It makes regular flights from Sydney to Los Angeles, carrying hundreds of passengers across 13,420 kilometres in about 14 hours. VH-OQG is also used on the world’s longest regular air route, from Sydney to Dallas/Fort Worth – a journey of 13, 804 kms that it completes in just 16 hours.

Ulm’s RAAF uniform cane and a commemorative airmail box, from Ulm’s flight to New Zealand in December 1933, are on display in the Museum’s new acquisitions showcase until 23 August 2015.

For more information: www.nma.gov.au/collection/highlights/aviation

Feature image: Ulm looks towards the camera, covered in leis, on arrival at Wheeler Field, Honolulu, 1 June 1928. Austin Byrne collection, National Museum of Australia.

[1] Letter from Hubert Wilkins to Austin Byrne, 29 October 1936. Austin Byrne collection, National Museum of Australia.

[2] Kingsford Smith and Ulm, Story of ‘Southern Cross’ trans-Pacific flight 1928, Penlington and Somerville, Sydney, 1928, p67.

[3] Ulm’s flight log, as published in Kingsford Smith and Ulm, Story of ‘Southern Cross’ trans-Pacific flight 1928.

[4] Ulm’s flight log, as published in Kingsford Smith and Ulm, Story of ‘Southern Cross’ trans-Pacific flight 1928.

The age of the internet is ever enlightening. I was watching a documentary via Netflix regarding the advent of forensic pathology in NY in the 1920’s. Amidst the anecdote of a man accused of murder and dismembement I noticed a snippet of a map from the cropped edge of the Ken Burns style newspaper insertion. Curiosity was ignited and after refining the search queries a couple times, The Oracles of Google pointed in your direction. Congratulations to those arrogantly, naively, ridiculously risky and brave Aussies. Thanks for sharing their story and I’ll keep them in mind next time I miss the exit on the freeway and think myself “lost”.