Bunnies by the boxful

Long before chocolate foiled-covered versions, the bunny was a familiar food to many Australians. Wild rabbits, the introduced European species Oryctolagus cuniculus, were plentiful and could be tastily cooked in a wide variety of ways. During peak periods of Australia’s ‘rabbit problem’ from the late 1800s through into the twentieth century, rabbit-dinners sustained many families, published recipes explained how cooks could get the best out of bunny, and associated meat and fur industries employed thousands. One object in the National Museum’s collection relates to the significant trade in rabbit meat, and to the long journeys made by millions of frozen rabbits from Australia to consumers overseas.

This post is the fourth in a series co-developed by Jono Lineen and other curators that explores Australians’ experiences with rabbits through objects in the National Museum’s collections.

Rabbits were among the first food animals imported to Australia. A small number – likely of a domestic breed then popular in Britain – arrived with the First Fleet in 1788. In the 1820s, rabbits were being sold at the Sydney markets along with chickens, turkeys and suckling pigs. In 1831 New South Wales’ Colonial Secretary Alexander Macleay was reported as potentially the first to establish a (well-stocked) rabbit warren in the gardens of his residence at Elizabeth Bay on Sydney Harbour. Rabbits were entered in early agricultural shows under the poultry category, allowing breeders to showcase their best specimens. The Sydney Poultry Society’s annual exhibition of 1858 generously awarded a first prize of £1 for best rabbit buck and doe pair.

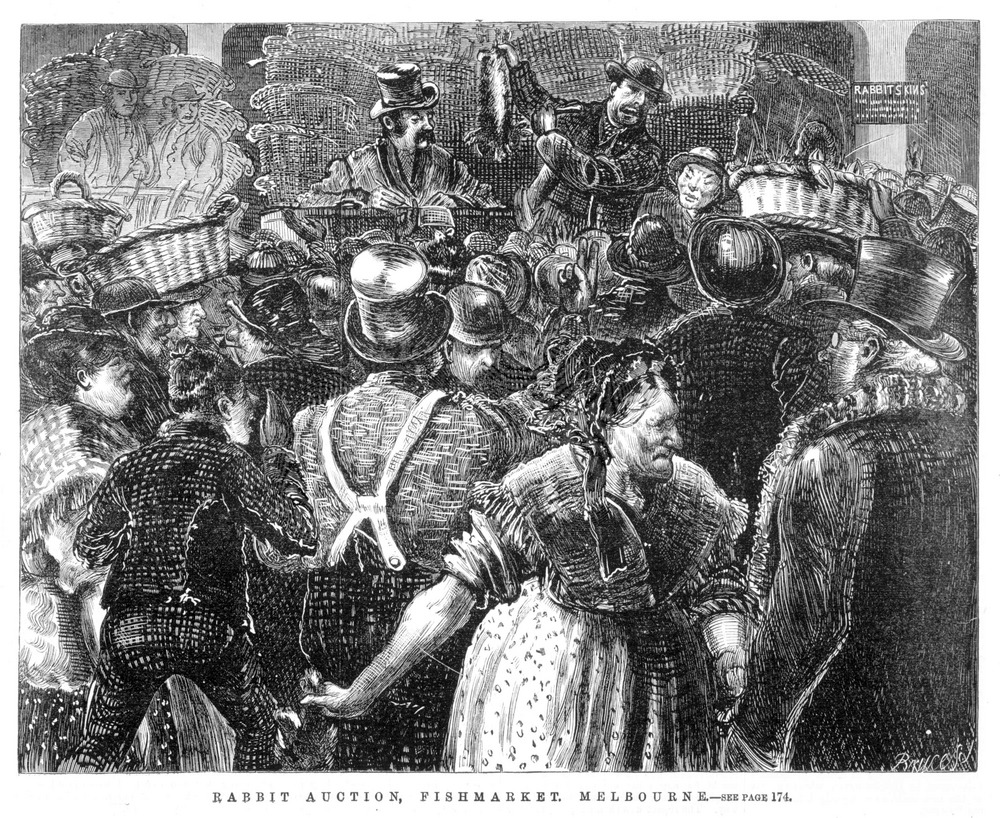

Through the 1870s, numbers of feral European rabbits (previously introduced for hunting) exploded in southern Victoria. Consequently, wild rabbit meat came to feature regularly at markets in this area.

Until the development of reliable facilities for chilling and transporting meat, most rabbit meat was consumed fresh and reasonably locally. From the late 1800s, advances in refrigeration, construction of freezing works and railway lines enabled more rabbits to accrue more food miles, more quickly. Rabbits could be caught, packed and frozen in the regions, then successfully transported to cities for export to Britain, North America, and Asia.

Yelarbon freezing works: ‘entirely for rabbits’

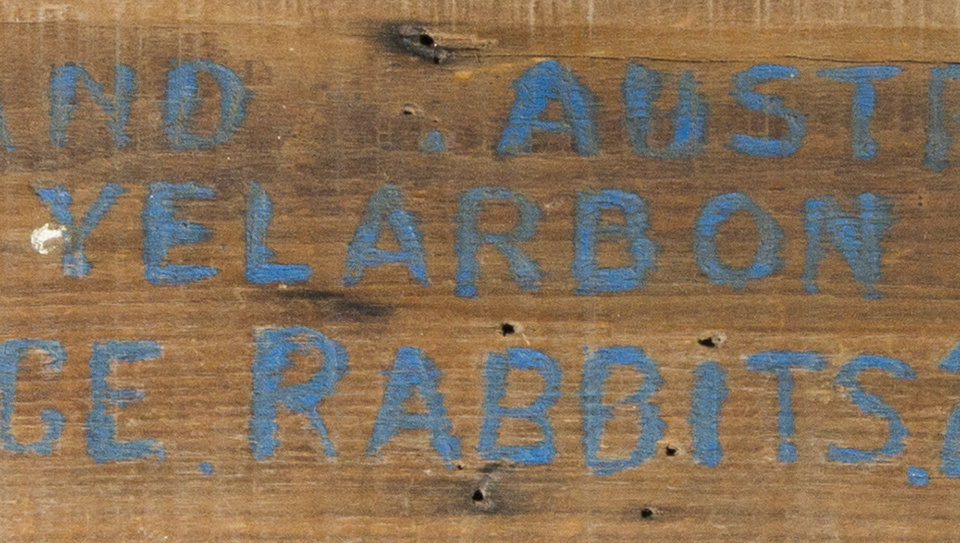

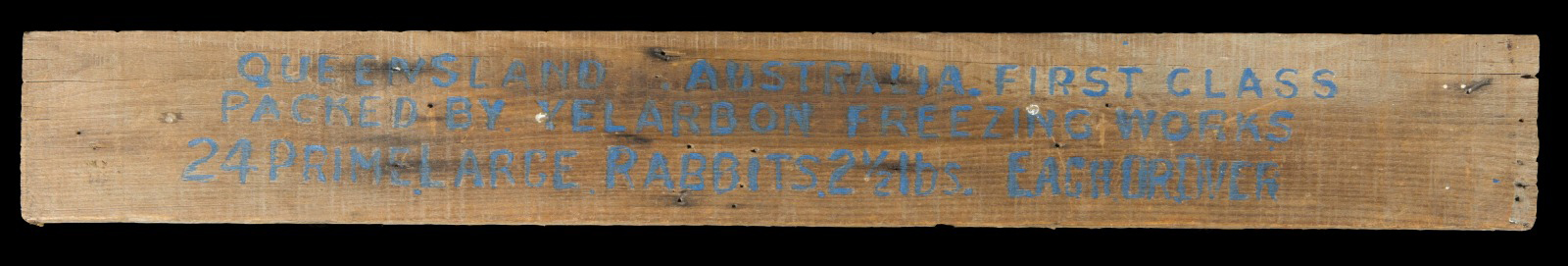

In the National Museum’s collection is a wooden panel from an export packing case for rabbits. Packing cases were simply and cheaply constructed from rough-cut timber and quickly stencilled with a description of their contents and place of origin. A single case carried 24 skinned, frozen rabbits from Australia via cold storage in a ship’s hold to buyers overseas.

Bert Wright collection, National Museum of Australia. Photo by George Serras.

This panel belonged to Bert Wright, who worked at the Yelarbon rabbit freezing works in southern Queensland during the 1920s-1940s.

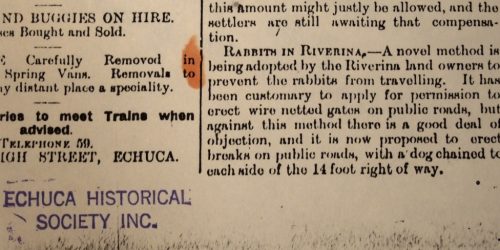

The Yelarbon facility, located near a rabbit proof fence along the border with New South Wales, was the first of its kind in Queensland. Unlike New South Wales and Victoria, Queensland did not support commercial dealings with rabbits. The Central Rabbit Board in particular strongly opposed commercial harvesting of rabbits for food or skins, on the basis that such a trade might encourage breeding of rabbits. After prolonged drought through the early 1900s reduced livestock and pushed up prices of other meats, and recognition that such an enterprise would provide employment to many in the local area, the Queensland government eventually granted a licence – under condition of twice-yearly reports – which allowed the rabbit freezing works to commence operation.

Bert Wright collection, National Museum of Australia. Reprography by Katie Shanahan.

Bert Wright collection, National Museum of Australia. Reprography by Katie Shanahan.

Opened in 1916, the freezing works supplied rabbit meat to markets around southern Queensland (Brisbane, Toowoomba, and Warwick), while pelts were sent to Sydney for auction and to hat factories in Melbourne. In 1917 the works processed over 110,000 rabbits. This success led to plans to expand capacity and establish exports.

‘The plant which did the freezing was small at first, supplying mainly Brisbane markets, but this grew until it was supplying a large city in Indonesia, then as the years went by, a firm in England…’

Bert Wright, 1992

Bert Wright was one of many locals who found employment at the works, operated in the 1920s by local businessmen Bill Wilkinson and Ted Maher.

‘I worked for the Yelarbon chiller for years on and off. The rabbit kept me in good work whenever I needed it. … I drove for them … from Yelarbon to Stanthorpe – 90 odd miles. Of course you were all over the place picking up, grading and buying rabbits. A docket was issued – so many pair of large, medium and small – all at different prices.’

Bert Wright, 1992

Bert recalled that in the interwar years (1919-1938) Yelarbon was known as a ‘rabbit town’. Over 20 tons of rabbits were trucked to Brisbane each week in peak periods and 151 trappers were on the freezing works’ books. During the 1930s Depression prices for rabbits were very low but trappers were able to make a little over £1 a week, enough for their families to survive the difficult times.

With the start of the Second World War in 1939, most of the young trappers enlisted for the Army and the flow of rabbit carcasses to the freezing works dropped significantly, but the company remained in business. Bert explained the impact that the absence of trappers had on rabbit populations: when the war finished ‘… there were rabbits everywhere – even living under the freezing works itself.’ The trappers came back and shipments of rabbits started coming from as far away as St George, approximately 250 km west of Yelarbon. The record catch Bert remembers was 4007 pairs delivered by one trapper in 1947-48. The works closed in 1955.

Bert Wright collection, National Museum of Australia. Reprography by Katie Shanahan.

Developing an industry

Even as availability of ‘raw materials’ swiftly increased through the late 1800s, focus remained on extermination, rather than exploitation. Passionate arguments were made for and against commercial exploitation of rabbits and trade in meat and skins. Landholders feared rabbits (a declared pest in many areas) would be left to breed for sale, thus compounding problems on the land. Other citizens pointed out that ignoring this free resource was wasting a potentially valuable opportunity.

In spite of objections, a rabbit meat industry slowly emerged from the 1870s. With more rabbits being trapped than could be sold fresh, meat-preserving companies became interested and canning factories were built and opened. However, rabbit canneries proved to be a short-term prospect only. The canning factory at Longwood in north-eastern Victoria began operation in 1891. Within a year it was employing 75 men at the processing works with another 150 trapping the surrounding area.

Photo by Michael O’Donnabhain via Flickr.

Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

‘On a good day the factory could turn out 4000 tins of rabbit, with meat from one and a half rabbits per tin. … But by 1898 the factory had closed down due to competition from the export trade in frozen rabbits. The rabbit exporters paid double the money for rabbit carcasses and the canning factory could not compete.’

Brian Coman, Tooth and Nail: The Story of the Rabbit in Australia, p102

Improvements in refrigeration in the 1880s meant that frozen meat could now survive the lengthy sea journey from Australia to Britain. Frozen rabbit exports commenced in the 1890s, albeit under protest from pastoral interests who believed that creating an external rabbit market would work against efforts to eliminate rabbits from the continent. Grazier Rupert Carrington observed: ‘ Encouraging this trade because it is good for rabbiters was like encouraging the smallpox because it was good for doctors.’ [1]

The industry continued to grow, however, and flourished through the first half of the twentieth century.

‘By 1929 the rabbit industry was reported to be the largest employer of labour in Australia. … The rabbit industry revolutionised work practices in rural areas and stimulated local businesses like no other industry. … Unlike other rural industries, the rabbit industry prospered during war, depression and drought.’

W. Eather and D. Cottle, The Rabbit Industry in South-East Australia, 1870-1970, 2015

Thousands came to be involved, doing many different jobs: from trappers to people involved in the preparation (skinning and gutting) of carcasses, those who graded, sorted, packed, chilled and transported rabbits, and those who supplied packing cases and other materials.

Photo: National Archives of Australia A1200, L2648

Photo: National Archives of Australia A1200, L2658

Families prospered from the industry and some grew rich. In the 1950s Victorian-born Jack McCraith became known as the ‘Rabbit King’. McCraith developed a centralised model whereby almost all rabbits sourced were shipped to his Melbourne factory. By the 1940s JA McCraith Rabbit Merchants had 184 depots set up throughout rural Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia, where trappers deposited and were paid for their catches. From these depots, within days, a cold chain of refrigerated trucks and train carriages brought the rabbits to the Melbourne factory. It was a hugely successful business. ‘From the late 1940s to the mid-1950s, [McCraith Co.] averaged about 1000 cases or 32,000 rabbits a week. At their peak they were exporting almost 100,000 rabbits a week. … Between 1945 to 1955 the market for rabbits was insatiable and the supply was inexhaustible.’ [2]

Photo: National Archives of Australia A1200, L2650

Figures provided by the Acting Commonwealth Statistician for only a 10 month period ending April 1947 noted that Australian exports of frozen rabbits and hares amounted to 10, 314, 817 pair (over 20 million), with a value of £1,480,906. The industry, however, was never stable. There were boom and bust years, very much dependent on drought conditions and the economy. Agricultural economist L J Dunn said in a report to the government in 1947, ‘The outstanding feature of an examination of the rabbit industry over a long period is its instability …’ [3]

From the 1950s onwards the industry faced major challenges. Changes in battery chicken farming introduced very cheap meat to the Australian domestic market. A newly established and large-scale Chinese hutch-reared rabbit industry led to increased competition with Australian rabbits in the European market. Combined with the devastating effects of myxomatosis on wild rabbit populations, a thriving industry was brought almost to extinction by the mid-1960s. Some decades later, proposals sought to continue rabbit exports in order to further reduce remaining wild populations, still an abundant pest animal in some areas. The unexpected transfer of Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease (RHD) or rabbit calicivirus onto the Australian mainland in the 1990s presented a further challenge as some overseas markets refused imports of rabbit products from locations where this disease was present. Unlike rabbit populations, the wild rabbit meat industry did not rebound or recover.

All ways with rabbit

‘The rabbit saved this country millions during the Depression years, and filled many a child’s belly which would otherwise have been empty…’.

Bert Wright, 1992

The association of rabbit meat with austere living earned it unflattering names such as ‘underground mutton’ and ‘poor man’s chicken’, however it provided good eating for many especially during the 1930s Depression, wartime and post-war periods. High cost and reduced or rationed availability of other meats challenged home cooks to come up with imaginative dishes that featured rabbit or which successfully disguised it (for example, as chicken). Newspapers and later women’s magazines regularly published recipes, with many running competitions that offered cash prizes for original creations. Submitted recipes were wide-ranging, reflecting British tastes as well as the influence of migrant cuisines on Australian food culture.

Fried rabbit, crumbed rabbit, rabbit pies, curried rabbit, fricasseed rabbit, rabbit puffs, rabbit rissoles, rabbit pudding, rabbit flapjacks (folded pancakes stuffed with savoury rabbit filling and grilled cheese topping), rabbit rolls, rabbit paste (for toast or sandwiches), rabbit Maryland, Mexican rabbit, Bengal rabbit, rabbit roly-poly (a baked dish with short crust pastry, potato, hardboiled egg and milk), rabbit in jelly, creamed rabbit, rabbit stew, puree of rabbit, rabbit stock (for soup), rabbit croquettes, rabbit noodle soup, rabbit balls milk soup, rabbit hot pot, steamed rabbit, roast rabbit, dried rabbit, rabbit cocktail, rabbit a la Italienne, rabbit a la chicken (Sydney Morning Herald recipe of the week in September 1947), rabbit brawn, rabbit ragout, Continental rabbit, rabbit galantine, rabbit relish, potted rabbit, rabbit fritters, rabbit and spaghetti casserole, choko stuffed with rabbit, rabbit and macaroni, rabbit with tomato and mushroom.

Some of the many rabbit recipes published in Australian newspapers, 1920s-1960s

Rabbit dishes also appeared in cookery books and were used to promote the interests of certain business organisations such as The Victorian Rabbit Packers and Exporters Association, which published ‘Rabbit Recipes’, written by Emily Noble, in 1930.

Wild rabbit meat is still available in Australia, however it is now mainly a feature of specialty butchers and fine restaurants rather than family dinner tables. The chocolate bunny – that specialty Easter treat – has resoundingly become our most familiar and preferred mode of ‘rabbit’. In recent times, concern over the ongoing presence and impact of introduced pest species such as rabbits on populations of native animals has seen promotion of an alternative icon for an Australian Easter – the bilby.

[1] Eric Rolls, They All Ran Wild: the story of pests on the land in Australia, Angus & Robertson, 1977, p77

[2] L J Dunn, The Rabbit Industry: An Economic Survey 1904-1947, Bureau of Agricultural Economics, 1948, p26

[3] Catherine Watson, The Rabbit King, Boniyong Pastoral Co., Niddrie, Victoria, 1996, pp67-68.

Fascinating details on the extent and contribution of rabbits to the pre 1950s Australian economy, especially in terms of food. I believe rabbit (or ‘Lapin’) fur coats were also once popular, and these of course are part of with what must now be the almost extinct trade of furriery.

And of course our famous Aussie Akubra hats were a side industry of note, being made from rabbit fur felt

A very informative report but did not answer my request of how much one paid for a pair of rabbits during the 1930’s. I did not mention buying them off the “rabbito” as he passed your house with his pole covered with pairs wich is how my mother bought them.It was probabley the same bloke that came past with a bundle of saplings on his shoulder ,calling out “clothes line props”.