‘Round the traps

This post is the second in a series co-developed by Jono Lineen and other curators that explores Australians’ experiences with rabbits through objects in the National Museum’s collections.

Rabbit trapping helped sustain many Australians through tough times of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, providing livelihoods, extra income or food. Rabbits were plentiful and trapping looked on as a simple way to convert a problem into something useful: money, a hot dinner or furred garment. Besides potential victims, prospective trappers had only a few basic needs: a trap, a hoe or setting stick, patience, and the ability to kill, prepare and transport captured animals. By the 1970s, when animal welfare legislation banning serrated steel-jaw leg-hold traps started being introduced, millions of traps had seen action – and rabbits – around the country.

The National Museum’s collections contain a number of well-used traps, including this Lane’s ‘Ace’ trap, specially designed for use in Australia.

A trap for Australian conditions

[I]t was Lane that produced the near perfect machine, the ‘Lane’s Ace’. It embodied all the features brought about by trial and error. Light, strong, fast, rust-resistant, it could be exposed to the elements for months, mislaid and left, then brought back into use immediately.

G. B. Eggleton, Last of the Lantern Swingers, 1982.

As rabbit populations in southern Australia surged from the 1870s, demand for traps likewise increased. Unlike rabbits, imported British-made traps did not particularly suit Australian conditions. Initial attempts to develop traps specifically for the Australian market based on British models fell short of the mark. New designs proved too heavy for commercial trapping in Australia as rabbiters often worked in isolated locations and over larger areas. ‘They should’a put a pair o’ bloody wheels on ‘em’ – was the recollection of one trapper recorded by G.B. Eggleton in his study of rabbiting in Victoria. [1]

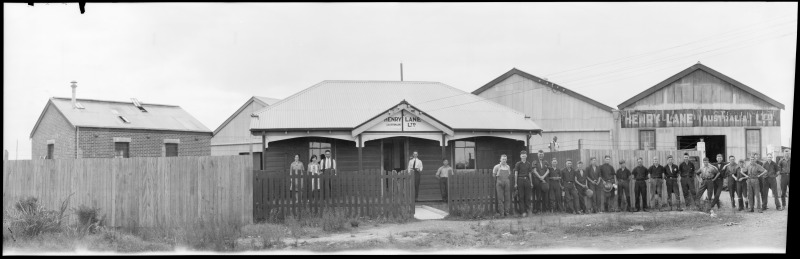

Early diagrams for a metal spring-jaw trap had been published in England in the late 1500s. By the 1700s, the design had resolved into a form similar to traps used in the 1900s. Improvements in steel quality and production methods in the 1800s saw development of a diverse variety of styles for use on all manner of mammals, many models prompted by the growing trade in fur for fashion. Established in Wednesfield, England in 1844, throughout the nineteenth century the Henry Lane Ltd company produced a wide range of metal animal traps (along with some man traps, primarily for use on private estates where poaching was a problem).

At the end of the First World War (1914-18), demand in Australia for traps was so great that Lane moved his rabbit trap production half a world away, establishing the Henry Lane (Australia) Ltd. company in Newcastle, New South Wales in 1919. After testing different steel, spring and pressure combinations, the ‘Ace’ trap came to fruition in 1935. The Lane’s ‘Ace’ design became the benchmark trap for rabbiting in Australia. Hundreds of thousands were turned out by the company and used around the country. Much copied by competitors, the traps remained in production until 1960. Although so many Lane’s ‘Ace’ traps were made, we’re fortunate to know the story behind this particular example.

Rolfe Bridle’s ‘Ace’ rabbit trap

National Museum of Australia. Photo by George Serras.” width=”440″ height=”293″> Lane’s ‘Ace’ rabbit trap used by Rolfe Bridle in the Blowering Valley, New South Wales, 1930s.

National Museum of Australia. Photo by George Serras.” width=”440″ height=”293″> Lane’s ‘Ace’ rabbit trap used by Rolfe Bridle in the Blowering Valley, New South Wales, 1930s. National Museum of Australia. Photo by George Serras.

This ‘Ace’ trap was used by Rolfe Bridle to catch rabbits in southern New South Wales during the 1930s. Made of carbon steel and weighing around 5 kilograms, time and outdoor use has lent it a patina of rust. It measures about 14 cm long. When the jaws are set open it stands about 7 cm tall. Attached to the spring end by chain is a 20 cm peg.

Born in 1916, Rolfe grew up on Brandy Mary’s Flat in the Blowering Valley near Tumut. He was one of ten children; his childhood home was a slab hut with an earth floor. Like many others of his generation, during the 1930s Rolfe lived a subsistence existence, relying heavily on trapping rabbits for food and selling their skins for 2 shillings 6 pence per pound.

In the hard times everybody, if they got out of work, first thing they’d do was have a bundle of traps and try. There was never any shortage of places to set them…. Back in the ‘30s Depression years, a lot of people would’ve starved if it wasn’t for the rabbits. It was the only meat they could ever get.

Rolfe Bridle, 1992

Rolfe often camped out in the bush when rabbiting, close to his traps. From his campsite he would set off carrying about 20 traps at a time, slung over his shoulder, holding onto them by the pegs. He would also have small pieces of newspaper pinned to his shirt; once the traps were set he would place a piece over the trigger plate to prevent dirt from falling into and clogging the mechanism.

Traps were pegged into the ground to keep them in place, however Rolfe used dogs to help locate traps in case they were moved from where he set them up. He recalled: ‘[S]ometimes there was a fox or even wallaby or kangaroo or something would get in the trap and they’d pull trap up, take it away… Well the dog’d find it’.

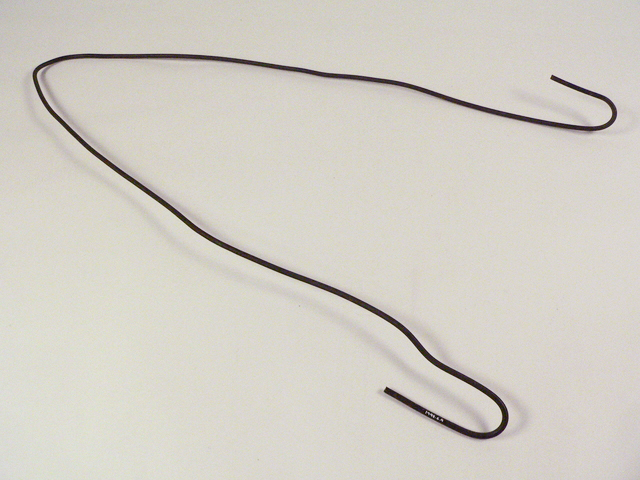

Rolfe mostly trapped for skins, as without easy access to refrigeration or a freezing works, by the time the catch was brought to the collection point the rabbits would be ‘off’. When he had caught about 20 rabbits, he would return to his campsite to skin them. Rolfe would eat some – cooking them in frypans over the fire – but mostly he discarded the rabbit carcasses. Once he had removed the rabbits’ skins, he dried them on wire u-shaped stretchers which were either stuck into the ground or hung in a tree to prevent dogs from eating them.

National Museum of Australia.

The trapper’s ritual

Rabbits are always quite silent once picked up. With no sound and no blood the killing can quickly be forgotten.

Eric Rolls, They All Ran Wild: The Story of Pests on the Land in Australia, 1977

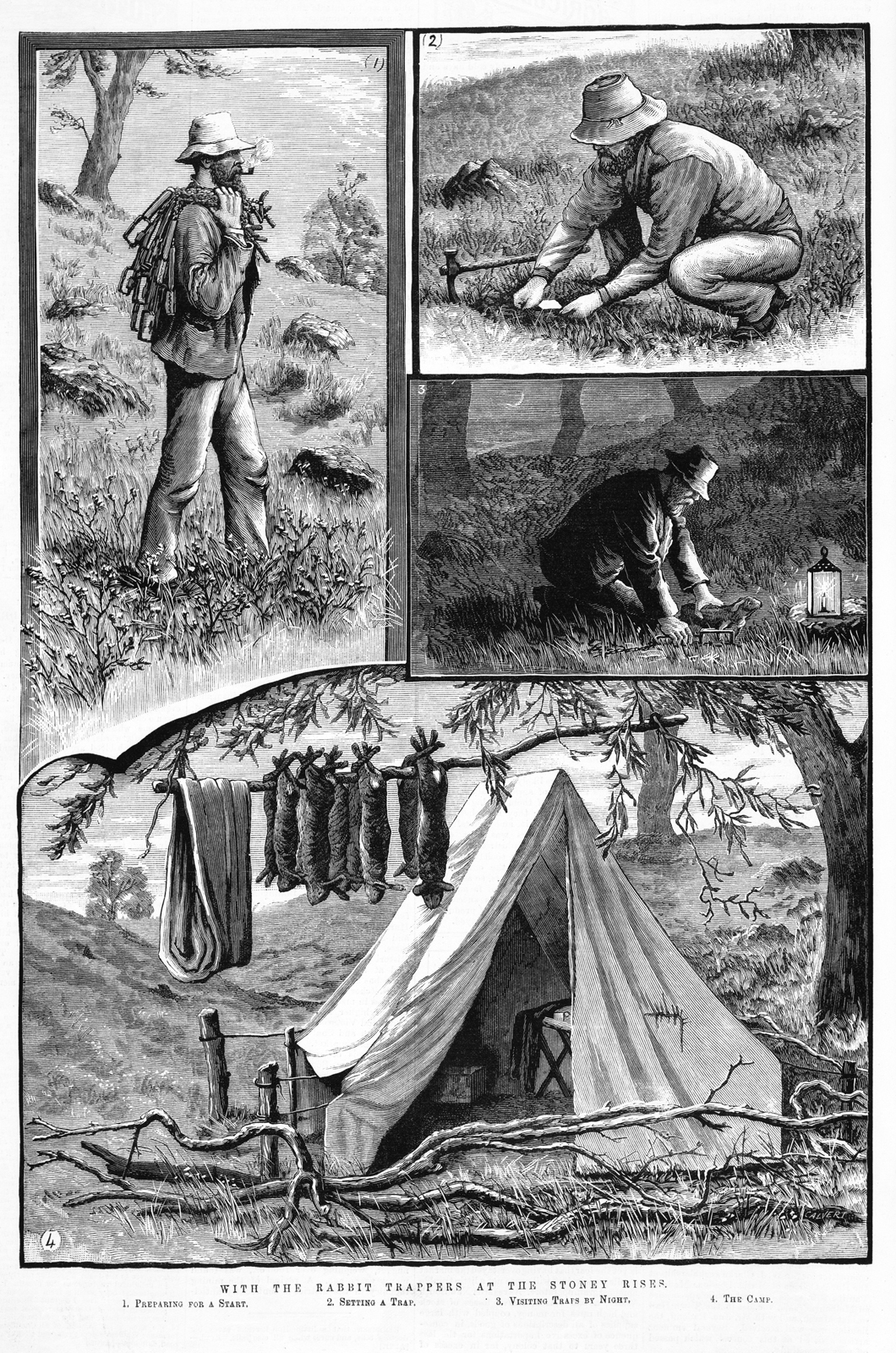

Rabbiters trapping for a living commonly worked and travelled with basic, robust equipment: bedding, a hurricane lamp, traps, a hoe, implements for skinning and drying skins, cooking equipment. Some took transport (a horse, small cart, or later, a vehicle) enabling a larger number of traps and rabbits to be carried, and used dogs. They often worked alone, in isolated locations.

State Library of Victoria.

When many traps were involved over an extended area, the work was often physically demanding. Trappers had to be able to carry traps and equipment, dig out a hollow for each trap, bang pegs into the ground, ‘set’ the jaws of traps open with their hands or using a setting-stick. They then had to return to retrieve their catch – ‘going around the traps’. In his detailed study of pests in Australia, They All Ran Wild, Eric Rolls likened the process to a ritual, noting that trappers had ‘a good memory for positions and their sequence.’ [2]

Traps were best set in spots where rabbits were active – near warrens and burrows, or around logs and dung heaps. When a rabbit stepped on the trigger plate, the trap was sprung; the weight of the rabbit depressing the plate released a catch which allowed the jaws to snap shut, holding the animal by the leg. Rabbits generally remained alive until the trapper returned and released them. Delay in checking traps could mean that rabbits had been eaten and the pelts ruined by predators such as foxes, crows or eagles.

After release, rabbits needed to be swiftly dispatched: trapping was not for those with a weak stomach. A commonly-used technique for killing rabbits involved breaking or wringing the neck (separating the brain from the spinal cord), producing a cracking noise. This method stopped breathing and blood flow to the rabbit’s brain, leading to death. Practice was required to perfect this technique, as Rolls vividly describes, ‘[t]he newcomer is likely to pull just a little too hard and finish with a jerking body in one hand and a severed head in the other. Such a mistake intensifies the deed.’ [3] Beginners faced other pitfalls.

Dead rabbits could be gutted and/or skinned, depending on whether the trapper was seeking a meal, working for saleable skins or meat. Rabbit bodies were typically carried or readied for transport suspended by their crossed feet – one leg passed through a slit in the other, creating a convenient suspension point – and paired.

National Museum of Australia. Reprography by Sam Birch.

![Inscribed postcard - 'This is one of the industries of Braidwood. This is a lorry load of rabbits being despatched to the freezing works[.] Some men earn from £10- to £12- a week trapping rabbits.They are very plentiful here.' National Museum of Australia. Reprography by Sam Birch.](/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/dams_dataprodderiv2jobswm_45806631nma-45806631-002-wm-vs1_o3.jpg?w=440)

National Museum of Australia. Reprography by Sam Birch.

Traps for rabbits were also put to other uses. Aboriginal artist Elaine Russell, who grew up at the Murrin Bridge Mission in the Central West region of New South Wales, remembers using rabbit traps to catch possums in the 1950s:

When you talk about setting rabbit traps naturally you would think it was for catching rabbits, but not in our case! My brothers and I would go into the bush and look for gum trees that had possum markings on them. Then we set the traps, put flour on them so at night the possums would see and smell the white flour and come down and eat the flour. Next morning, before we went to school, we would check to see if we had caught any possums which would become our supper that night. Mum would cook possum stew and freshly baked damper.

Elaine Russell, 2002

Work created under the National Museum of Australia Artist in Residence Program. Photograph by Dean Golja.

A profitable activity

You can’t go wrong for rabbits: they’re everywhere. And they’re as good as cash all the time.

Unnamed rabbiter quoted in the Evening News (Sydney), 25 May 1906, p4.

The ‘favourite method’ – suggests Rolls – of the Australian rabbiter, trapping was extensively used during periods of great abundance in rabbit numbers, particularly from the 1880s and into the first half of the 20th century. Though found to be inefficient as a form of rabbit control, trapping grew in popularity as value of the catch came to be recognised.

Various industries started to emerge as the commercial value of rabbits was realised. In the 1860s and 70s, rabbits trapped on properties in Victoria’s western districts (an area where rabbits brought ruin to many farmers) were principally used for food, transported the short distance to Melbourne for sale at the Fish Market. By the late nineteenth century rabbits were being sent to factories where their meat was preserved or their fur processed into felt hats; bales of pelts and crates of frozen carcases were also being exported overseas. Thousands found employment as these industries grew; more and more rabbits were needed, and destined, to supply them.

In the 1880s, schemes – designed to induce widespread action on rabbit control – involving governments and landowners paid subsidies for rabbiters work and bonuses for rabbit scalps. Open to exploitation, unscrupulous practices abounded (leaving rabbits to ensure future supply, faking or recycling scalps, inflating associated costs). The system proved very expensive for authorities and did not result in less rabbits, yet provided incentive for prospective trappers.

Many rural and urban people – unemployed and casual workers, tradesmen, professionals, families – were attracted to trapping as rabbits were easily caught and good money was able to be obtained for their skins and carcases. W. Eather and D. Cottle observed in their recent study of the rabbit industry, each time prices for rabbit carcases and skins reached new heights, more people would seek to try their luck at trapping: ‘[c]ontinual waves of new workers entered the industry, with contemporaries likening each influx to the 1850s gold rush’. [4] At times, trapping proved to be such a profitable activity that successful rabbiters were able to live very comfortable lifestyles.

During periods of economic depression, drought and war, rabbits were a free and accessible food source for many Australian families. Many improverished rural people relied on rabbits to survive; rabbit meat, however, gained negative associations. In Tooth and Nail: The Story of the Rabbit in Australia, Brian Coman wrote that until recently, rabbits were: ‘… the poor man’s food… In the eyes of middle-class Australians, particularly landholders it was something of a social stigma to eat rabbit. It was even more of a stigma to be a rabbiter.’ [5] Despite this, Eather and Cottle suggest that ‘the well-to-do also ate their fair share of rabbit’ with rabbit meat ‘consumed by rich and poor alike in cities and towns across Australia’. [6] For young people during the 1930s and 1940s trapping rabbits also provided an effective means of making pocket money.

With the start of the Second World War manpower for rabbit trapping was absorbed by the war effort. Rabbit control simultaneously suffered and in the post-war period the wild rabbit population flourished. Increased demand for skins and meat also saw ‘earnings reach astronomical levels during the 1940s and early 1950s… with some trappers earning up to £100 per week.’ [7] This was not to last.

End of an industry

From the 1950s, the deadly myxomatosis disease – developed in order to combat the rabbit problem – spread and decimated populations, with far fewer rabbits left to supply now major domestic and export industries. For Jack McCraith, founder of a successful rabbit meat supply business: ‘The myxo virus only meant you had to go further to get the rabbits… but to compensate, a world-wide shortage of rabbits meant they were worth a lot more.’ [8] The increased price also meant that many people could no longer afford to buy rabbits to eat from the local butcher. Trapping continued but in the 1960s was dealt a double blow from which the commercial industry could not recover: producers in Europe and China increased production of farmed rabbits, with China becoming the largest exporter of meat from domestic rabbits; and the introduction of battery farming for chickens in Australia offered consumers a cheaper, more reputable alternative. Large-scale commercial trapping ended at this point.

Humane alternatives

Brian Coman collection, National Museum of Australia. Photo by George Serras.” width=”440″ height=”292″> This rabbit ‘jump-trap’ with black rubber-lined jaws was designed in America as an humane alternative to traditional serrated-jaw traps. It was imported into Australia in the 1980s and used for research in Victoria.

Brian Coman collection, National Museum of Australia. Photo by George Serras.” width=”440″ height=”292″> This rabbit ‘jump-trap’ with black rubber-lined jaws was designed in America as an humane alternative to traditional serrated-jaw traps. It was imported into Australia in the 1980s and used for research in Victoria. Brian Coman collection, National Museum of Australia. Photo by George Serras.

Through the 1960s and 1970s animal welfare groups lobbied for the prohibition of serrated steel-jaw leg hold traps due to concerns over unnecessary pain and prolonged suffering faced by animals caught in them. The closing force of the jaws and placement of the serrations can damage limbs, and frightened animals can sustain further injuries attempting to get out of the trap. Most Australian jurisdictions have now passed legislation banning such traps with use subject to varying penalties that extend to large fines and/or prison terms of up to two years. Use of serrated steel-jaw traps (with cloth binding soaked in strychnine) for wild dog control is still permitted in some parts of Australia.

Australian Capital Territory – Animal Welfare Act 1992

New South Wales – Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1979

Northern Territory – Animal Welfare Act 2000

Queensland – Animal Care and Protection Act 2001

South Australia – Animal Welfare Act 1985 and Animal Welfare Regulations 2012

Tasmania – Animal Welfare Act 1993

Victoria – Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1986 and Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Regulations 2008

Western Australia – Animal Welfare Act 2002 and Agriculture and Related Resources Protection (Traps) Regulations 1982

Rabbit trapping still continues in Australia with soft-jawed leg hold traps or cage traps, however commercial harvesting of wild rabbits for food and skins now mainly involves the services of a professional shooter. Whatever the method, the boom years of big money in rabbits are long gone; the rabbits are not.

[1] G. B. Eggleton, Last of the Lantern Swingers, 1982, p14

[2] Eric Rolls, They All Ran Wild: The Story of Pests on the Land in Australia, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1977, pp80-1

[3] Ibid., p83

[4] Warwick Eather and Drew Cottle, ‘The Rabbit Industry in South-East Australia, 1870-1970’, Proceedings of the 14th Biennial Labour History Conference, eds, Phillip Deery and Julie Kimber (Melbourne: Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, 2015), pp11-12

[5] Brian Coman, Tooth and Nail: The Story of the Rabbit in Australia, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 1999, p97

[6] Eather and Cottle, op cit., p10

[7] Ibid., p15

[8] Catherine Watson, The Rabbit King, Boniyong Pastoral Co., Victoria, 1996, p172