Among the plants

Last week, we installed nine objects from the Museum’s collections in an exhibition at CSIRO Discovery in Canberra. These objects – including microscopes, a vasculum, and a billy-can – tell us much about the careers of the women scientists that used them, and about women’s participation in scientific endeavour in the last 150 years.

The League of Remarkable Women in Science exhibition has been developed by Anne-Sophie Dielen and Britta Forster, biologists working at the Australian National University, in collaboration with the National Museum of Australia.

Dielen founded the League of Remarkable Women Scientists in 2014. “I had a lot of issues with self-confidence and a belief that I wasn’t good enough to be able to do this [research work],” Dielen told the ABC. “And I found it very sad and scary to see that in some of my students too. … So I wanted to give female university students and high school students positive examples, and show them stories, and have role models and mentors.” Since then, she has interviewed more than 40 women scientists in Australia and internationally about their experiences.

The exhibition, at the CSIRO Discovery Centre, combines images and quotes from contemporary women scientists, with showcases featuring a selection of objects from the National Museum of Australia’s women scientists collections.

The National Historical Collection has a rich vein of material relating to Australian women scientists, particularly those who worked in the early to mid-20th century, largely thanks to a targeted collecting project carried out by Ruth Lane in the mid-1990s. Biologists feature prominently in these collections, because women were (and are) more strongly represented in biology than in other areas like physics or chemistry. The reasons for this are complex – and still the subject of debate and research. A century ago, when most of the women represented in our collection were at school, biology, and botany in particular, was an area of study deemed acceptable for women. Plants and flowers carried feminine associations, and natural history study had been part of girls’ education for centuries.

The Museum’s collections relating to women botanists reveal women studying plants in the field and in the laboratory. Here are some of their stories, and their objects currently on display in the exhibition. The text was written by Martha Sear (Louisa Anne Meredith and Ilma Brewer) and Kirsten Wehner (Winifred Curtis and Jean Galbraith).

Louisa Anne Meredith

Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office

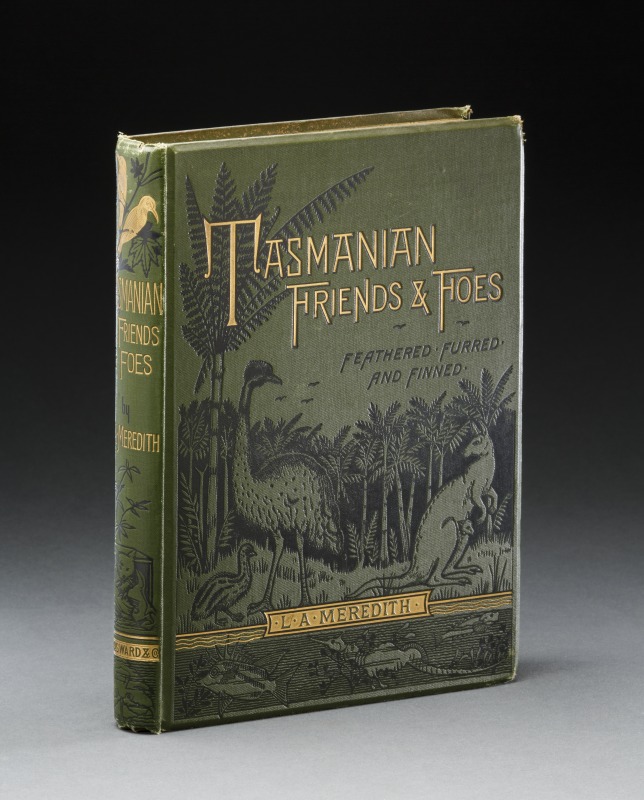

Author, artist and natural history collector Louisa Anne Meredith (1812-1895) was born in Birmingham, England, and educated at home. Throughout her twenties she exhibited paintings, published poems and articles, and supported herself financially by writing and illustrating books on British flowers and scenery. Meredith arrived in New South Wales with her husband Charles in 1839, and moved to Van Diemen’s Land in 1840. The ‘gossipy chronicle’ of their early experiences became a bestseller, and she subsequently published fourteen popular books recording her observations, with both pen and paintbrush, of colonial life, landscapes and native plants and animals. She also won prizes for her natural-history themed writing, art and embroidery at intercolonial and international exhibitions, collected plants, animals, algae, fossils, and shells, and corresponded with scientists around the world on Tasmanian natural history. She was elected an Honorary Member of the Royal Society of Tasmania (the only woman among 50 men) in 1881, and in 1884 the Tasmanian Government granted her a £100 pension in recognition of her ‘distinguished literary and artistic contributions’ to the colony.

Aimed at ‘young readers’, Tasmanian friends and foes tells the story of a family writing letters ‘home’ to British relatives about their experiences of life in the colony, including their encounters with native marsupials, birds, fish, reptiles, and insects. Most of the anecdotes were drawn from the lives of Meredith and her circle. Meredith frequently claimed, as she does here, that she did not ‘presume to offer scientific information’, but her detailed depictions of both the appearance and behaviour of plant and animals meant that her books appeared on the shelves of many scientists, including Charles Darwin. The book includes a list of algae collected by Meredith herself and scientifically-named by Swedish seaweed expert Professor C. S. Agardh.

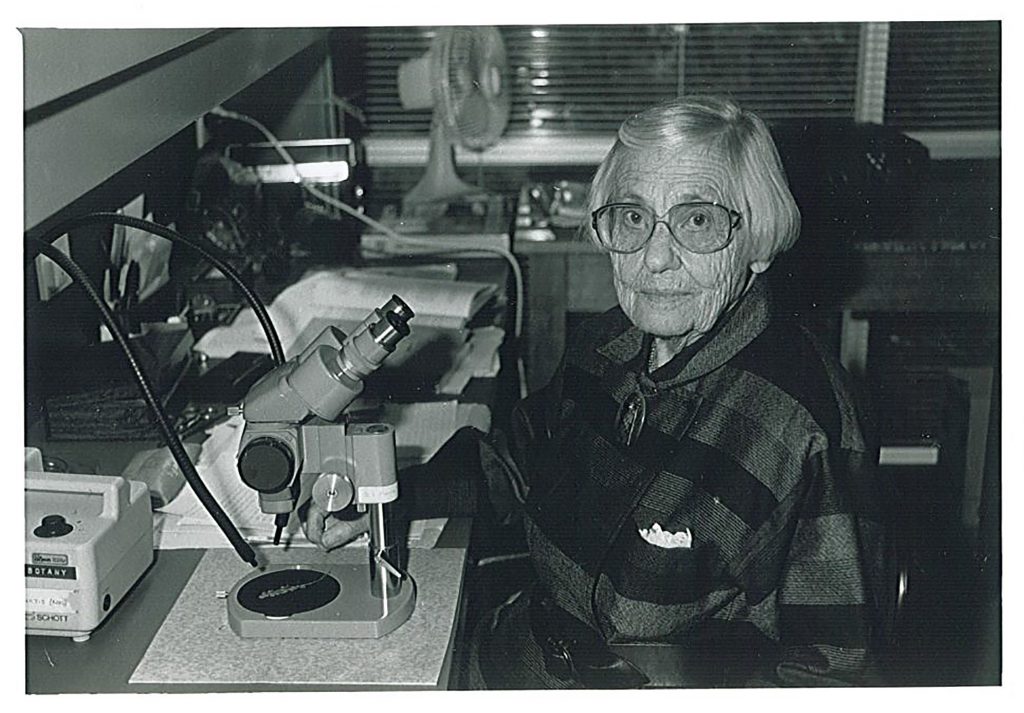

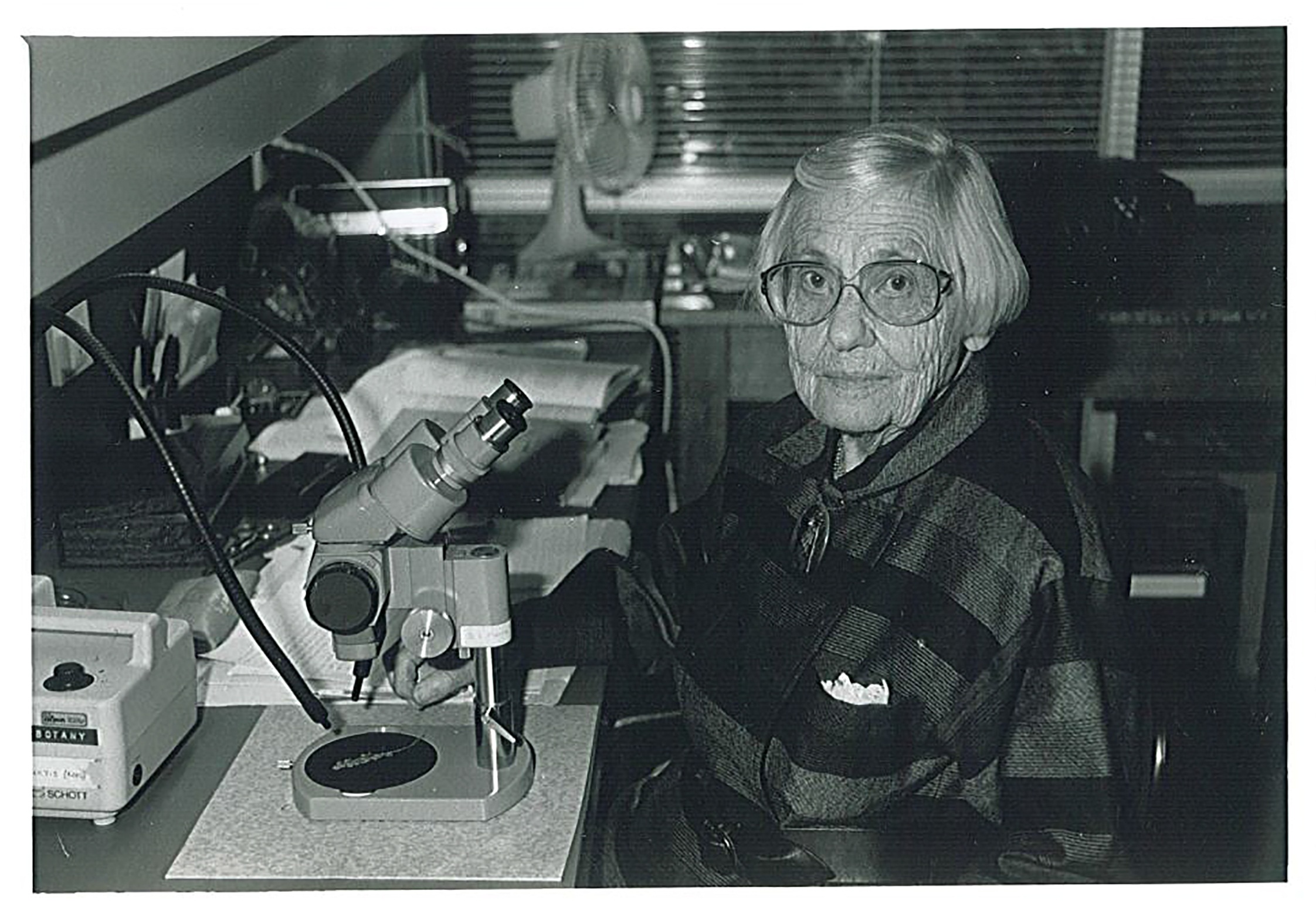

Winifred Curtis

Botanist Winifred Curtis (1905 – 2005) migrated to Australia from England in 1939 and joined the Biology Department of the University of Tasmania, the second woman appointed to the university staff. She helped found the Botany Department in 1945, eventually rising to become Reader and Acting Head, and received her PhD (1950) and DSc (1968) from University College London. Curtis conducted ground-breaking research on plant cytology, embryology and taxonomy, helped develop the Tasmanian Herbarium and published two definitive, multi-volume handbooks The Students’ Flora of Tasmania (1956 – 1994) and The Endemic Flora of Tasmania (1967-1978). She was awarded membership of the Order of Australia in 1977.

Curtis purchased this vasculum in England when she started collecting plants at around age fifteen. She brought it with her to Australia, but found it unsuitable for Tasmanian conditions. Not only did the metal get too hot in summer, but it proved too small to hold the stiff, prickly local flora. When plastic bags became available, Curtis started using them instead.

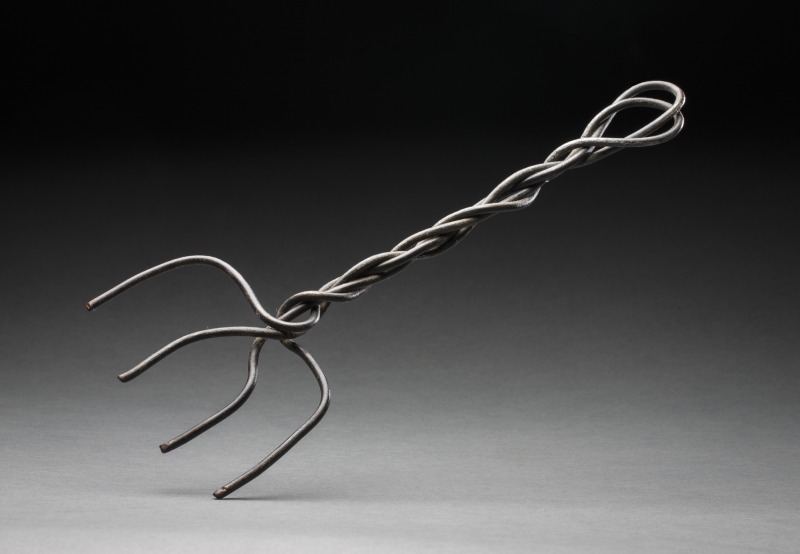

Jean Galbraith

Botanist, author and conservationist Jean Galbraith (1906 – 1999) lived in Gippsland, Victoria. She left school at age 14, but through the Field Naturalists’ Club became a skilled plant scientist. She was passionate about native flora and over her lifetime produced hundreds of articles, stories and radio broadcasts educating Australians of all ages about local plants. In 1950, she published Wildflowers of Victoria, the state’s first accessible field guide. Galbraith was also a lyrical and evocative gardening writer who inspired many Australians from the 1920s to the 1970s to grow natives.

Galbraith often camped out in the bush for extended periods, observing and recording plant species and collecting seeds and seedlings for her garden. With only a modest income and no institutional support, she frequently relied on home-made equipment.

Ilma Brewer

Botanist, plant ecologist and educator Ilma Brewer (1915-2006) was fascinated by Australian plants as a child, and went on to study botany at the University of Sydney. As part of research towards her Doctor of Science degree, Brewer (then Ilma Pidgeon) developed a new technique called ‘isonome mapping’ to study changes in the plant species seen in sandstone and dune country in central coastal New South Wales, which contributed to larger efforts towards soil conservation. She also undertook statistical analysis of the regeneration of vegetation following grazing at Broken Hill, and during World War II mapped coastal vegetation for military intelligence. In 1943 she married United States Army lieutenant Dick Brewer. As a married woman she could not hold a professional position, and for 10 years she maintained a modest research profile while caring for her husband and children, initially in Connecticut USA.

The family returned to Australia in 1948, and in the late 1950s Brewer took up a teaching role at the Botany School at the University of Sydney. Enrolments were growing, and Brewer initiated televised lectures – but soon realised students were bored by them. Inspired by overseas examples, in 1972-3 she set up a teaching laboratory based on self-paced instruction and small group learning – officially called the Ashby Audio-Visual Learning Centre, it became known as ‘The Brewery’. She retired and published a book on her teaching methods in 1978. In 1991, Brewer collaborated with another researcher to study changes in mined dunal vegetation near Hawks Nest, drawing on observations she had made in the 1930s and 1940s. Their work was published in 2003.

Students in Brewer’s teaching laboratory worked at their own pace through a sequence of recorded lectures, microscope slides, notes, diagrams and exercises, explained in a study guide like this one.

——

Do you remember these women scientists? Why have women pursued careers in botany – and what has enhanced or inhibited their participation in the biological sciences? We’d love to hear your views in the comments section below.

Hi there, great article, thank you for raising our awareness of brilliant women, but can I suggest the last paragraph should read either Do you remember, or, remove the question mark at the end of the sentence.

Oops! Thanks Susan, have fixed that up!

Shirley Jeffrey was another fantastic scientist who paved algal taxonomy in Australia.

Reblogged this on Firn Research Group QUT and commented:

Celebrating the league of remarkable women in Australian science with our pioneering naturalists that forged the way forward for understanding Australian plant communities. A must read and must see if you you will be Canberra some time soon.