Water objects in the collection

I’m a volunteer in the People and Environment curatorial team, and I’ve just started working on an online feature about water history.

Recently, on a bakingly hot day, I had my first visit to the Museum’s stores. It was a little bit Dr Who, frankly. Some of what I saw could easily have come off a set from the Tom Baker years. The Doctor, in whatever regeneration he’s in, has the capacity to produce from the bowels of the TARDIS some object that saves the day, or provides a vital clue to the mystery that’s currently baffling him. The store felt like it could easily be at the end of one of the TARDIS’s interminably long corridors.

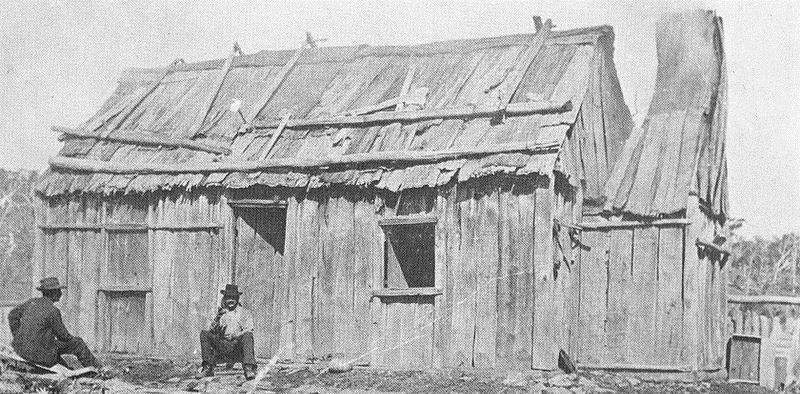

In the store, I came across an object that catapulted me back in time about a decade and a half. It was a timber cart from Yungaburra, still caked in moss and lichen despite the great gulf in climatic conditions between Canberra in a heatwave and the wet tropics in the wet season.

I’m from Perth originally, where I grew up thinking sand was soil, that it never rains in summer and that the sun always sets over water. In 2000, I moved to far north Queensland. Echoing environmental historian Eric Rolls, I thought I’d moved planets. Soil meant thick, sucking red mud, the sun sets over land and in the first week I was there, it rained more than I was used to in an entire year. It was so damp and humid that mould would sprout on any wood surface overnight, so that you could stumble out in the morning and have to disinfect the dining table before you could spread out the newspaper. Let me not mention the pythons, cane toads and ginormous spiders….

We all have set points, so to speak. By that, I mean our yardstick for normal, which is frequently a matter of instinct rather than thought. We don’t usually think we have environmental set points, until something happens to tip us beyond them. My move to the wet tropics upset every single one of mine, and was a decisive turning point for me. I was suddenly an alien, and my relatives treated me with kindly condescension. ‘It’s all right, she’s from the south. She’ll get the hang of it.’

That experience of being a stranger somewhere totally foreign is what all migrants go through. It’s just that I hadn’t left Australia. It’s no accident therefore that what became my doctoral research on water history focussed on how people understand a new environment. It’s no accident it was about water either. Having come from south west Western Australia where water availability is not exactly niggardly, but certainly constrained, to the unusual experience of saying ‘Does this rain ever stop?’, my experience of water had been enlarged. If I’d stayed in Perth I might never have thought about it any other way than how I always had; arriving in winter, refusing to play in summer. Air so dry it sucks the moisture out of your skin.

I moved back to Perth because I couldn’t hack the humidity, and stayed there for a few years until I moved to Canberra, to undertake that aforementioned PhD. I’d never lived inland before either. But I felt less of an alien in Canberra because I still recognised the vegetation. In Cairns, I had re-learn everything. While I didn’t like the heat or the humidity, I did appreciate the amazingness of green. I’d never lived anywhere so permanently lush and abundant. God, there are even trees on the beach!

Trips to the Flecker Botanic Gardens slowly got my eye used to the intricacy and variety in leaf shapes, and how many different shades of green there can be. Palms finally looked like they belonged, instead of being marooned on a western sand plain and underplanted with Iceberg roses and diosma. All that made possible by the quantity and timing of rainfall.

I’ve never treated water with the same casual comprehension again. We can’t live without water. This fact of life goes with the one about paying tax and dying. My north Queensland experience opened my eyes to how diverse water is, and now I see water’s influence everywhere.

It’s in the processing water than helped make the plastic of the keyboard I’m typing on. It’s in the water that irrigated the crops that fed me last night. It’s the restful view of the lake that this museum sits by. It’s in the cooler air beneath clumps of trees, transpired out by the process that makes likes life on earth possible: photosynthesis. It’s the stuff of political battles, and happy holiday memories. Water is integrated into our spiritualties, and in our practicalities. Every time we drink, cook, bathe and water the garden, water is there supporting us. We speak with the language of water. I’m parched, we say, or it never rains but it pours.

Over the years, societies have made a substantial array of objects to celebrate it, control it, and make use of it in a multitude of different ways. The Museum’s collection contains some intriguing and some commonplace water objects. Curators have already worked on a number of online features related to water. This new feature will complement what has already been done, by highlighting the diversity of water in Australia. It will take you through every state and territory, and from the small scale to the massive, the artistic to the practical. The feature is part of the Museum’s desire to make its collection more accessible. We recognise that our space is limited, and not everyone can visit. An online exhibition that grows over time will hopefully address some of these issues, and will give insight into both the diversity of water as a substance, and the diversity of the Museum’s collections.

I hope you enjoy it.