“If a tree falls in a forest…”: International Mother Earth Day

Friday 22nd April is International Mother Earth Day and the theme for this year is ‘Trees for the Earth’. Earth Day has been around since the 1970s, but since 2009 the day has been reconnected — somewhat quaintly — with the idea that planet earth is feminine. Interesting, but let’s leave that for another blog post. For this year’s Earth Day I decided to conduct an experiment, running a very simple search on the National Museum’s collection explorer, just to see what might pop up in relation to trees and forests.

The Museum holds a remarkable array of objects related to Australian forests, both in terms of the history of their commercial exploitation as well as the groups that have worked to protect them. The system randomly arranged images of collection objects, but it was the pairing of two intriguing images that caught my eye.

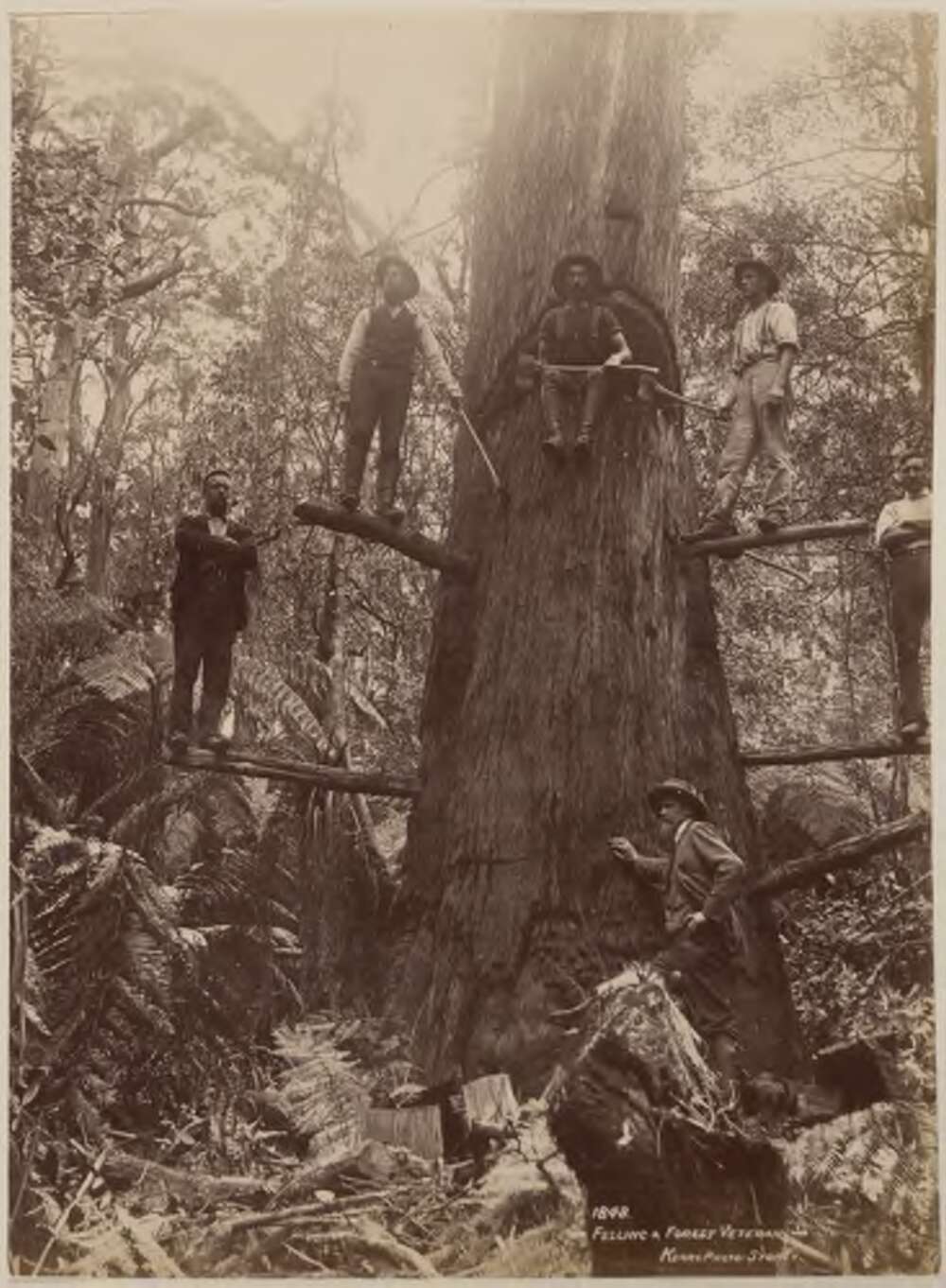

The first shows a group of loggers in New South Wales in the late nineteenth century, having paused from their job of felling a mighty tree to be snapped by popular Sydney photographer Charles Kerry. Although the men are dwarfed by the ‘forest veteran’, the image is unambiguously masculine. It suggests the rightfulness of hard labour and the idea that the abundant and limitless resources of the land would sustain the growth of Australian cities and towns.

These heroic and muscular representations of settler’s relations to trees were common for the time, but they were by no means the only kind of interactions being documented. Next to this picture on my search page, appeared a much quieter vision, but one no less affecting.

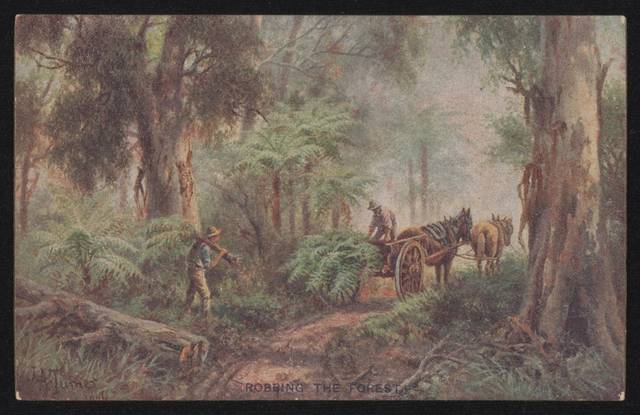

James Alfred Turner’s ‘Robbing the Forest’, painted in 1906, depicts two men cutting and loading tree ferns onto a wagon in the Dandenong Ranges, east of Melbourne. Domestic and international demand for ferns grew steadily in the latter half of the nineteenth century, and there was plenty of easy money to be made by those with the knowledge and means to access local forests. While the title leaves no question of Turner’s opinion of the exploitation he describes, as a local property owner, the vantage point for this work is of the hidden observer, documenting and reporting the interactions with the landscape. In stark contrast to the proud loggers in Kerry’s photograph, the men here work furtively under the canopy, quietly desecrating the forest.

These two representations are a reminder of how contested and vital forests have been in Australia. They are also a reminder of how early European settlers began to express their concern at the rapid depletion of those landscapes. Of course, Turner wasn’t the first to recoil at the plundering of the country’s natural resources. Environmental concern in Australia grew rapidly from the mid-nineteenth century, as the quest for gold revealed the capacity of diggers to shape and utterly transform great swathes of land.

Australian artists and photographers were among the first to record the damage to natural ecosystems and note the land’s inability to adapt to such rapid and radical over use. Although many were preoccupied on an aesthetic level with the disruption to scenes of natural beauty, their work helped inspire the emerging naturalist movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and their efforts to conserve and restore the natural world. On International Mother Earth Day, a quick scan of the Museum’s collections offers a sobering reminder of the enduring contest over the value of Australian forests and the powerful role they have playing in the national imagination, both as a fragile ecosystem to be nurtured and as a resource to sustain and extend European settlement.

What to know more? You can read about another giant Australian tree called ‘Big Ben’, and the tradition of naming trees in a PATE blog post from a few years ago.