Post-traumatic stress and the long Shadow of Ebola

After 42 days without a new case of Ebola, Liberia is officially now ‘free’ of the disease, as of 9 May 2015, according to the World Health Organization. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-05-09/liberia-declared-free-of-ebola-disease/6457992 On-going vigilance is urged; there are still new cases in neighbouring Sierra Leone and Guinea, and diseases do not respect national jurisdictions.

Liberia’s battle with the deadly disease within its borders continues too. There is a long shadow cast by the grief for the 4,716 people who have died (as of 6 May), and the 5,848 survivors and their families who are trying to rebuild their lives amidst the post-disease chaos. A disease that kills nearly 45% of those who contract it leaves survivors feeling almost guilty about being alive. Even a full recovery can be stressful. Survivors are very likely to also be grieving lost family. The disease does not ‘go away’ after 42 days. The street artist who painted a wall in Monrovia, Liberia’s capital, declaring ‘EBOLA IS REAL’ was not just providing important public health advice at the time. The shadow cast by the disease on the community could outlast the paint, and the consciousness that his wall arouses in the city becomes ever more important as the world’s attention moves elsewhere.

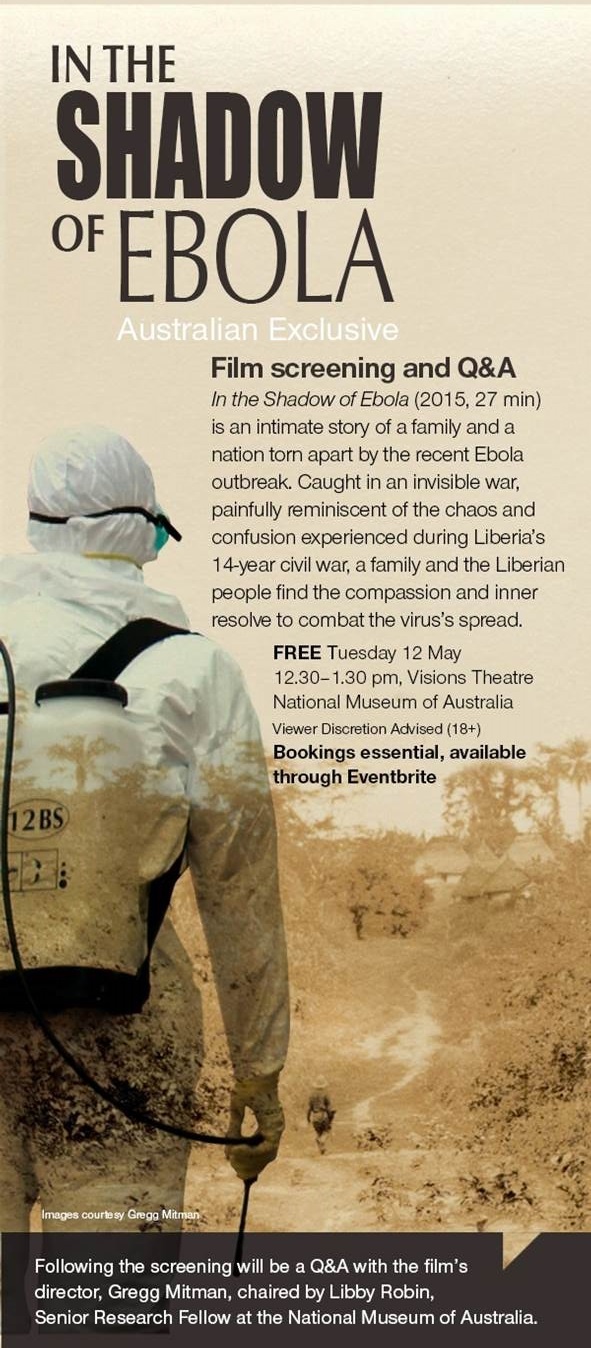

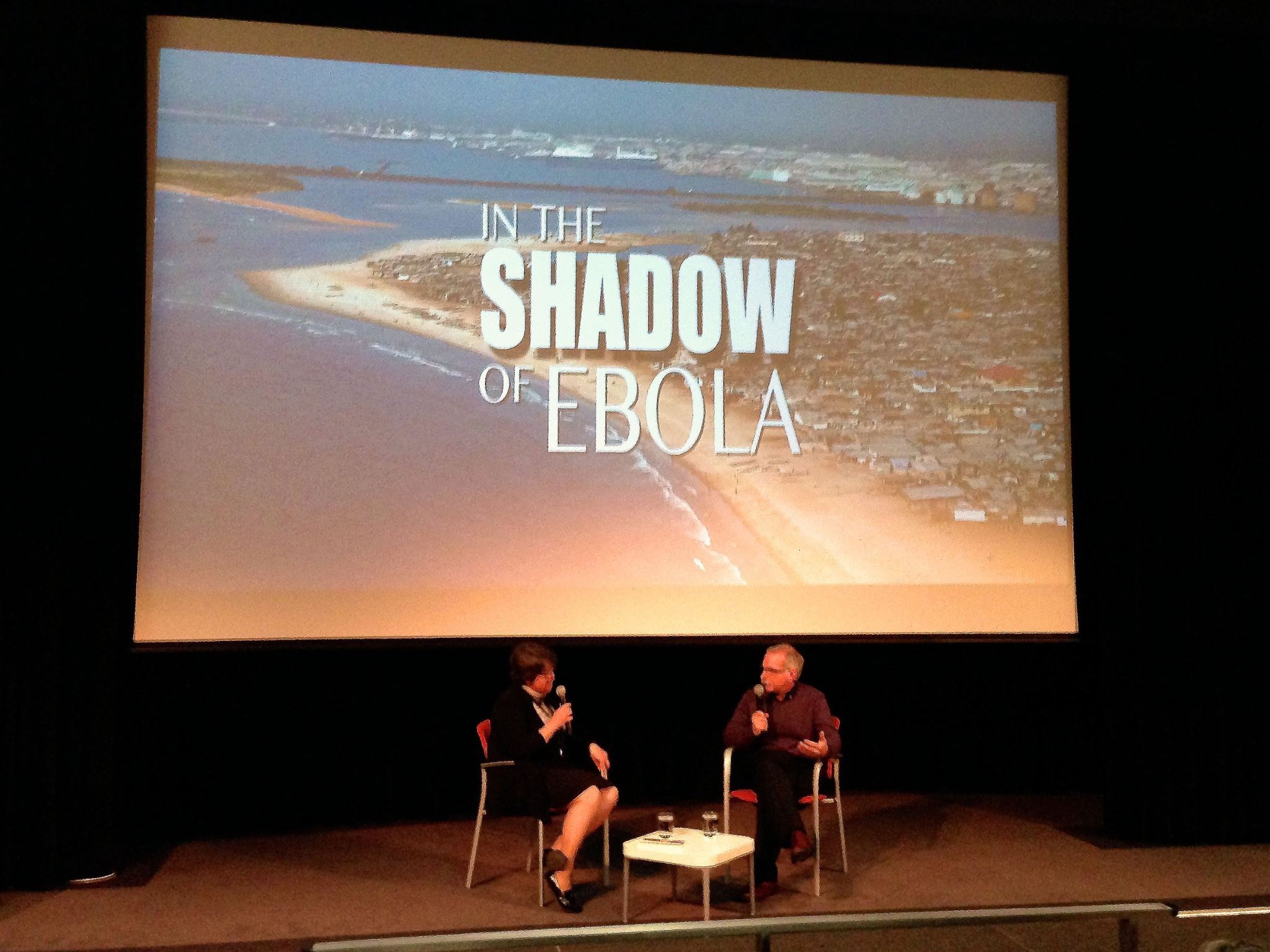

The National Museum of Australia was privileged to hold the premiere Australian screening of the new film In the Shadow of Ebola on 12 May 2015. Gregg Mitman, historian of medicine and film-maker was our special guest. The film began in June 2014 as the first cases were emerging, and at a time when no-one could foresee how it would end. It is a confronting film that portrays the difficulties Liberia faces, a country that is still reeling from successive civil wars from 1989-2003, whose people have reason to fear military-style interventions even those with a public health motive. Nevertheless it reveals the power of the Liberian people to do things for themselves, in the time before any international aid reached them.

With few doctors and very poor hospitals and clinics, the task of alerting people to healthy behaviours – “wash your hands!” – fell to Hip-Hop Disk Jockeys and street artists. It was striking that the community, particularly in the city, which was paralysed by border control against disease for months, cutting off citizens from fresh food and water, rallied and worked out solutions. The international news always concentrates on international aid, and deaths of foreign doctors, but a film like this can capture some of what it felt like to be stranded by Ebola from family abroad, from urgent supplies and from good medical advice. Australia was the first country to close its borders to West African travellers, and has the most explicit Ebola travel documents for everyone entering the country from anywhere overseas. Gregg Mitman fielded a range of audience questions about making the film and the on-going situation in Liberia now. We have established a new Australian website http://ceh.environmentalhistory-au-nz.org/2015/05/shadow-of-ebola/ to enable the conversation to continue with Emmanuel Urey, the Liberian star of the film, who is based with Gregg at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

|

In the Shadow of Ebola (2015, 27 min) is an intimate story of a family and a nation torn apart by the Ebola outbreak. Caught in an invisible war that is painfully reminiscent of the chaos and confusion they lived through during a fourteen-year civil war, a family and a people find the compassion and inner resolve to combat the virus’s spread. Trailer: https://vimeo.com/123541483 Comments: http://ceh.environmentalhistory-au-nz.org/2015/05/shadow-of-ebola/ |

At times Australia feels very far from West Africa and its concerns. Yet on the day of the film’s screening, the Camp Draft was cancelled in Aberdeen, New South Wales, because of the fear of another bat-borne haemorrhagic disease, Hendra, a disease in the same family as Ebola. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-05-12/bats-cancel-campdraft/6463992

Following the major floods in the region, Grey-headed Flying-fox Pteropus poliocephalus had migrated in vast numbers, posing what public authorities felt to be a major disease risk to horses and their handlers, so organizers decided to postpone the event http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-05-12/6464102 . There was also discussion about closing the local school next to the Flying-fox colony.

The NMA hosted the screening of In the Shadow of Ebola as part of a longer interest in using history as a tool for communities to take control of their lives after stress. The National Museum and the Centre for Environmental History were leaders of a bushfire project in Victoria that undertook work in a small community affected by the 2009 fires, which I reported in an earlier People and the Environment blog: https://pateblog.nma.gov.au/2013/12/16/stories-for-healing/ Post-traumatic stress is an important element in these very different events, and historians and film makers are working to contribute in complementary ways to medical professionals, as well as to document initiatives that might be helpful for people under stress in future epidemics, fires and other traumatic events, both in Australia, and around the world.

David Quammen, the distinguished science writer, produced a wonderful book, Ebola: The Natural and Human History of a Deadly Virus (Norton 2014). If it were to become a film, it would be the chase for a ‘cause’ of the disease – and the race for a ‘cure’. Gregg Mitman, as a historian telling a story in place, as it unfolds, has given us quite a different film: it is not about the cause, but rather its effects. Mitman recognises that the story of an epidemic is not just about the disease, but also about how the people affected live with it, and adapt to the stresses of its long shadow on their lives. Good public health policy depends on both perspectives: a scientific understanding of how the disease emerges and can be treated, and a historically nuanced, compassionate understanding of how people can support each other through the post-traumatic stress of an epidemic.

STOP PRESS:

If you missed the screening on 12 May, due to popular demand, there is to be an extra screening of In the Shadow of Ebola in the Australian National University’s John Curtin School of Medical Research on

Wednesday 3 June at 12.30

Finkel Lecture Theatre, Level 2 (Room 2.006) Building 131, Australian National University

(near the Vanilla Bean café)

Further details on the website: http://ceh.environmentalhistory-au-nz.org/2015/05/shadow-of-ebola/