The Chinese in Bendigo – processioning towards acceptance

A spectacular Chinese ceremonial costume was recently installed in the Museum’s Landmarks: People and Places across Australia gallery and it got me thinking about the lives of all those who for over a century wore this intricate creation – proudly and somewhat defiantly – as part of the annual Bendigo Easter Fair. You see, before this costume and many like it joined the extensive regalia collection at the Golden Dragon Museum, they played a functional and public role in the life of Bendigo’s prominent Chinese community and, by extension, the town’s general population. Yet the costume’s most important role, I suspect, was as a powerful emblem of cultural identity for the Chinese residents, who faced prejudice and discrimination both on and off the goldfields.

The Chinese – predominantly men from the southern province of Guangdong – first arrived in the area within a couple years of gold being discovered at Bendigo Creek in late 1851. Having escaped major political and social upheavals back home, they were lured by Victoria’s alluvial gold deposits and hoped to make a good enough living to send remittances to their impoverished families in Guangdong. Between 1854 and 1859, 30,000 Chinese travelled to the Victorian goldfields and, by 1857, they made up nearly 40 per cent of Bendigo’s male population.

Diggers from all over the world, including Europe and America, joined them at the diggings, but the flow of Chinese prospectors created fear and resentment among the European population, who regarded them with general suspicion and mistrust. In June 1854, a mass meeting of European miners condemned the ‘Chinese invasion’ and threatened to forcibly expel all Chinese from the Bendigo field. The action never eventuated, but resentment continued to simmer and the colonial government introduced discriminatory taxes in an attempt to discourage Chinese migration. These included a ten pound tax imposed from 1855 by the Victorian government on each Chinese immigrant arriving in the state, as well as an additional residential levy imposed on residents of Chinese camps, which were administered by European authorities.

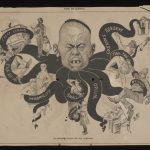

A cartoon and accompanying article that appeared in The Bulletin on 21 August 1886 unashamedly captured the discrimination and racial vilification to which Australia’s Chinese residents were widely subject. The illustration, which appeared in a special edition devoted to exploring the issue of Chinese immigration, depicts a grotesque caricature of a Chinese face with eight tentacles emerging from it, each labelled with an alleged vice or threat associated with Chinese immigration. The accompanying article – ‘The Chinese in Australia Their Vices and Their Victims’ – further sets out The Bulletin’s concerns about Asian labour undermining Australian workers’ wages and accuses Chinese migrants of directly causing an alleged increase of social ills such as prostitution, gambling, drug addition, disease and corruption. A clipping of the newspaper’s overtly racist and biased feature is held by the Museum and features alongside the costume in the Bendigo section of the Landmarks gallery.

By the time The Bulletin began its prominent anti-Chinese editorial position in the 1880s, many Chinese miners had already returned home over the preceding two decades after alluvial gold ran out in Bendigo and the Chinese found themselves largely excluded from mining the rich gold deposits found in the quartz veins that lay deep beneath the town. Those who remained turned to other occupations that serviced the miners who continued on in Bendigo – becoming successful market gardeners, opening stores and taking up various other trades and professions. Many of those that remained lived in settled camps, or protectorates, which allowed their residents to enjoy social life, religious traditions and cultural practices alongside their compatriots. Europeans sometimes stigmatised the camps as unsanitary and immoral, though they were actually relatively clean for the conditions of the time, but the general distrust with which the Chinese tended to be regarded made them anxious to contribute to the welfare of the Bendigo community.

One of the earliest and most effective ways in which the Chinese were able to not only ingratiate themselves with the goldfields’ other inhabitants, but also gain respect for their cultural practices, was through participation in public performances and festivities. Theatrical troupes, formed by Chinese migrants, sprung up soon after migration from China to Victoria began. Boasting displays of dance, mime, sword-play, music and acrobatics, they toured Victorian gold diggings and initially performed only within their own camps, though occasionally they were joined by Europeans who had succumbed to that irrepressible human condition – curiosity. By 1858, however, what had been considered for years as a ‘fringe’ activity made it into the mainstream when a troupe performed at Haymarket Hotel’s theatre in Bendigo to a mixed crowd of delighted Chinese and somewhat confused but fascinated Europeans. Over the following decade, Chinese operas, which drew on traditional folklore, legends and famous historical events, regularly appeared in mainstream theatres and, judging from their promotion in newspapers such as the Bendigo Advertiser, regularly drew European audiences.

Having found a common ground and wanting to contribute further, from 1859 Chinese theatre companies followed a precedent well established by European theatres and began putting on benefit performances for charities, leading to their participation in the Bendigo Easter Fair. The Fair, which bad began in 1869 as an event aimed at raising funds for the local hospital and Benevolent Asylum, first attracted modest Chinese participation in 1871. By 1879, however, the Chinese had secured a formal place in the proceedings and became the main attraction of the Easter Monday procession, with video footage captured a century later confirming their lasting popularity. Through this participation, the traditional performances and festivities of Australia’s Chinese migrants – previously considered just a marginalised curiosity of the camps – were effectively transformed to the centre-stage of a public event that celebrated civic values and goodwill, and was shared by the whole community.

Demonstrating their determination to attain respect and build mutually co-operative relationships, the Chinese community spared no effort or expense in their contribution to the fair, and in 1882 commissioned from Canton (Guangzhou) a hundred crates of ceremonial regalia for use at future processions. The arrival in 1892 of an additional 200 crates filled with more costumes and ‘Loong’ – a 60-metre imperial dragon – meant the Chinese of Bendigo were no longer forced to borrow regalia from other districts and indeed enabled them to loan out their holdings to other Chinese communities as far afield as Tasmania and Sydney.

The jacket recently installed in the gallery is believed to have arrived as part of the first shipment and represents the procession’s ‘General of Military Forces’. A highly regarded position sometimes charged with leading the Chinese contingent, it was shared by both Chinese and European men (as seen here, here and here) and women over the history of the event. The intricately embroidered jacket was worn with pantaloons, shoes and headdress, however the style of the additional items depended on the gender of the wearer. Illustrating a female performer’s use of this jacket, or another just like it, is a series of studio photographs of Mabel Wong – a member of the Chinese community is Sydney who often also performed in Victoria.

The ‘General of Military Forces’ costume, which was used regularly from the 1880s until being replaced in the 1980s, is currently on loan from the Golden Dragon Museum for display in the Landmarks gallery. It replaces a processional Princess costume that was likewise loaned from the Golden Dragon Museum, which holds a world-class collection of Chinese ceremonial regalia – much of which dates from the 1880s and boasts long-term use in the Bendigo Easter Fair processions. Engaged in not only collecting, preserving and caring for Chinese cultural material, the Museum also aims to ‘promote goodwill and understanding between Chinese Australians and people of other races and nationalities’ – an aspiration so closely and beautifully in keeping with the spirit of its charges.

If you would like to find out more about the Chinese in Bendigo, check out our recorded curator’s talk or visit our generous lender, the Golden Dragon Museum in Bendigo, who we’d like to sincerely thank for their support and congratulate on a fabulous collection.

Top Image: Ceremonial ‘General of Military Forces’ costume used in Chinese Procession of Bendigo Easter Fair, 1880s. Courtesy of Golden Dragon Museum. Collection Bendigo Chinese Association.

I like this article. Maybe I am bias because I worked with Russell and Joan Jack in building the Golden Dragon Museum. While many of the historical facts were well known, your article, however, is insightful. The Chinese not endured severe hardship after they have landed in Australia, they also suffered terribly during their voyages from China to come to this land of hope. Over two third were indentured labourers “selling the piglets” and were confined to the lowest level of the ship. Sometime in cages. 2 or 3 of them were tied together by their pigtails/queues to prevent them from escaping. Almost a third perished on the voyage over.

The dragon is in the Golden Dragon Museum is actually the largest one of its kind in the world and definitely worth checking out if you down there for any one interested. Thanks for the article Karolina, its always inspiring to here about anyone that travels far for their own success and overcome adversity. It’s really makes you think, the Chinese were willing to travel so far for what they wanted , live with racism and over come it. What can we do with our own lives. There are so many opportunities out there, how far will we go to make things better for ourselves and our families. ( it may not be in distance but in other areas if that makes sense)