Museums as Places for Imagining the Future of Cities

Dr Steven Fleming has been poking the hornets nest that is urban planning for over a decade, with his mission to put cycling on the agendas of architects, politicians, designers and academics. Together with his colleague Professor Angelina Russo, he has been holding a series of provocative workshops around the country to get people thinking about the potential for bicycles to change the shape of our cities and the way we live. What’s different about these workshops is that they are being hosted by museums and will be run in conjunction with the National Museum’s Freewheeling: Cycling in Australia exhibition.

So why are Museum’s the best place to re-imagine the physical and cultural fabric of our cities? I’ll hand over to Dr Fleming, for his point of view……..

Isn’t it fascinating, given all the possible fates for our species (from life in deep space to loosing our war against microbes), that when anyone talks about the city of the future having more cars, taller buildings and wider roads, our response is to shrug and say, “yep, that sounds about right.” That’s what most Australians are doing right now, as we have a national conversation around what have been dubbed the “roads of the 21st century”. On both sides of politics it is assumed that new roads have more lanes, wider lanes, more cars… more speed. Any debate is around whether rail would not be a wiser investment, not whether roads in the 21st century might throttle car traffic. It seems unthinkable to us in Australia that new roads in this country might be like the new roads London has just started building, with fewer lanes, to carry less cars.

If London is building new roads for fewer cars (my god, what a concept!) well then according to those of us here in Australia that would just be because London is a whole other beast. We think of it as a city from the old world that has just been dealt a dud hand. London’s streets are barely wide enough for two donkeys to pass—or so we tell ourselves here.

If London is building new roads for fewer cars (my god, what a concept!) well then according to those of us here in Australia that would just be because London is a whole other beast. We think of it as a city from the old world that has just been dealt a dud hand. London’s streets are barely wide enough for two donkeys to pass—or so we tell ourselves here.

At the same time we tell ourselves that our own cities were designed for cars from the outset. But hang on, weren’t Australian cities and European ones all defined, size wise, by the same growth spurt? The industrial revolution came to London first, but not by hundreds of years. And wasn’t the industrial revolution more or less over before cars were prolific? By the way Australians speak about our cities being built around cars, you would think all our property alignments were surveyed in the 50s. Most of our streets are much older.

There is no point asking what makes Australians so stupid. Emotionally, mathematically, and in spelling tests, we do fine. It’s only with our U.I.Q.s (urban intelligence quotients) that we fall down.

The real question, is who gave us this warped understanding of our own urban planning genetics? We have a meta-narrative about roads carrying more cars by the decade and roads getting wider until all of our buildings are like pencils on-end. We need to know the source of this furphy.

The real question, is who gave us this warped understanding of our own urban planning genetics? We have a meta-narrative about roads carrying more cars by the decade and roads getting wider until all of our buildings are like pencils on-end. We need to know the source of this furphy.

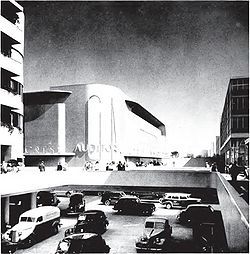

Here are some names of designers to google: Sant’Elia, Ludwig Hilberseimer, Bryan de Grineau, Harvey Wiley Corbett, Le Corbusier and Norman bel Geddes.

We would not know any of these visions or names though, were it not for their backers: powerful car manufacturers like Voisin and General Motors, manufacturing demand for their products, and producing space where their products could be put to full use. Yes, the sad truth about our shared vision of the “city of the future” is it came to us via commercials. The most powerful was GM’s Futurama exhibit at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York.

And haven’t these ads been successful! Just look at how much of the land area in this typical Australian town centre (Launceston) has been designed with the automotive industries’ customers at the forefront of everyones thinking. (Image source.)

If you want to walk in an Australian city, rather than using a car to drive from one store to the next, you will be confined to narrow footpaths, and even then not have the freedom of walking. One must be ready at any moment to stand aside for drivers as they barge in and out of car parks mid-block.

In these ways the automotive industry has been winning more public space for its customers by the year. But there is a new territorial claim. Lobbyists for pedestrians, cyclists and public transport, have found a raw nerve. It’s not the death toll, pollution or the cost to the government of sedentary lifestyles. It is the urban mobility challenge. On roads laid out before WW2, cars can’t deliver people to jobs as quickly as buses, cycling and walking can. Wider footpaths, protected bike lanes, designated bus lanes and next to no room for private cars is the new future vision for inner suburbs and city centres. The automotive industry has reason to fear that vision for London, pictured above, will become the shared vision all over the world. Yes, even in a car-obsessed place like Australia.

Their answer: autonomous cars. Controlled by computers these promise to be able to platoon at high speed in the city and negotiate intersections without ever having to stop or slow down on approach. An image emerges of streets like conveyors, sorting and distributing more people by car than healthy-and-green modes can ever compete with.

[vimeo 37751380 w=640 h=385]

As someone who has studied urban cycling in places like the Netherlands today, and elsewhere in the past, I’m not quite so in awe of computers steering cars through intersections like this. Groningen’ssimultaneous green traffic light phasing shows that cyclists can do the very same thing, without crashing, at close to their full cruising speed, even when they are banked up and released all at once.

But for Australians, I know there are two problems with this example. First, it is from a city that be can dismissed as belonging to the old world, where people have been dealt a dud hand. Never mind the actual width of Groningen’s roads (most are quite wide) we tell ourselves they’re all medieval. Second, examples from the Netherlands lack the sublime power of technological visions. Show us pneumatic trains, maglev and robot cars. Since the mid 1800s (eg 1,2,) it has been the hi-tech means of connecting people to jobs that Australians, the British and Americans crave. It seems oxymoronic to say this, but the conservative approach to urban mobility is to look for experimental technology.

In our own homes, of course, the scales are reversed. Filling ones kitchen with electronic gadgets from infocommercials is viewed as shortsighted. The thinking person looks to simple tools sanctioned by centuries of faithful service: wooden chopping boards and knives built forever; scissors; mortars and pestles; gas burners; hand-held whisks, and such utensils. When deciding what to buy for ourselves the progressive choice is time-honoured. When deciding what to invest in as a society, the conservative response (as mad as this sounds) is to take a wild punt on some new contraption.

One way to tackle this, is to ask where the future is imagined. I don’t mean, “where is the future imagined to be?” like on one of Jupiter’s moons. I’m asking where people are gathering to imagine the city of the future. In most cases, alas, their desks, computers and meeting rooms are on commercial premises, serving vested interests. The public enterprise of imagining the future is being undertaken by private entities. In the tradition of Le Corbusier imagining a city for Voisin automobiles, or Norman Bel Geddes imagining a city for General Motors, car companies are once again sponsoring leading designers to imagine the city of the future, this time driverless cars at the centre. Audi’s patronage of Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) is a prime example, although there are others.

Looking at BIG’s work for Audi you could start to believe the automotive industry is investing billions to create a cyclists’ and pedestrian paradise! Crossing a road filled with one continuous platoon of cars will not (as I would have thought), be like sticking your fingers into a fan. No, the robot behind every wheel will be Astro Boy. It will be programmed to do no harm to no person, not even mischief makers bringing the system undone for a laugh (as I would do) or wanting to use streets for free (as I would do too, on my bike).

Following is a more realistic vision of a future of autonomous cars, not sponsored by the car industry, and in this case exhibited in a public museum.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I6_yLXQkK40?wmode=transparent&fs=1&hl=en&modestbranding=1&iv_load_policy=3&showsearch=0&rel=0&theme=dark]

That example shows the power of creative artists and public exhibition venues to critique privately sponsored visions that really only exist to manufacture demand and lay claim to space. Work I’ve been doing with the National Museum of Australia (NMA), The Queensland Museum (QM), Professor Angelina Russo (a Museums sector expert at the University of Canberra), and community members who have come to our workshops, shows the power of museums, visionary thinkers, and people with no profit motive: we are able to conceive alternative visions. They may not be as futuristic as any imagined by purveyors of autonomous cars, but they are more progressive, in the sense that a kitchen with better utensils and a tighter ration of modern appliances is considered progressive.

Encouraged by the NMA’s Freewheeling: Cycling in Australia exhibition (that includes some of my own explorations into the architecture of a purpose-built bicycling city), we have ran workshops in the QM and NMA, with more planned for other museums. Each workshop has started with a bicycling tour to gauge the distance, by bike, to underdeveloped brownfield and greyfield land in each city. That is followed by a tour of the Freewheeling collection to gain an historic sense of the bicycle’s role in the development of this nation; as Jim Fitzpatrick has explained, it was the bike, not the horse, that enabled many of Australia’s industries to source labour.

Photo from Brisbane bike tour by Angelina Russo

Then it’s over to me. My job has been to explain a hypothetical model for city planning that promises average commutes of 18 minutes in cities of six million people. I ask workshop participants to imagine a 15km diameter circular city with the same average population density as Manhattan, ie, 3o,000 people per square kilometre. Next they are to imagine this hypothetical city having such a tight ration of motorised vehicles that cyclists are never held up. Finally, I ask them to imagine an utterly permeable ground plane, achieved by a combination of short blocks, chamfered corners and buildings partially raised on piloti. (The architectural forms that I believe would optimise cycling are the subject of this article I wrote for ArchDaily.)

- ©cycle-space.com

- ©cycle-space.com

- ©cycle-space.com

With a little maths, and a little rounding of figures up and back down, it can be shown that any parent with a baby and some groceries aboard a Dutch box bike, could complete two thirds of all possible trips in 18 minutes on average. That’s one way of saying a purpose-built bicycle city in the 6,000,000+ population category would save people a third of the time Texans spend commuting in conurbations with the same populations. Here’s a link to those calculations. (They can send me the nobel prize in the mail—it might be too far for me to ride to accept it in person.)

Image: Martin Ebert

The role of workshop participants has been to imagine ways this imagined model might be incorporated into their own city (so far, Brisbane and Canberra) without necessarily impacting people in those cities who are attached to the car and sprawl lifestyle.

Photo from Brisbane workshop by Angelina Russo

As it happens, most Australian cities have enough negative space within a 15km diameter sphere, that a few million extra souls could live in the manner I just described.

In the case of Brisbane, a lot of the under utilised land is low lying. Every major Dutch city could be built in the space that Queenslanders have rejected because it seemed easier to extend roads to highlands than protect the lowlands from flood.

Photos from Brisbane workshop by Angelina Russo

When finished, a similar map of Canberra that my office has started will show an equal amount of left-over space. In Canberra’s case it includes a lot of lake-side land that can’t be accessed by vehicular traffic because the arterial roads bordering those sites cannot have spurs added without interrupting the flow of car traffic. This is of no concern though for anyone happy to access a new development solely by bike.

Photos from Canberra workshop by Angelina Russo

At the risk of pre-releasing key findings (these workshops themselves are the subject of an ongoing study), I’ll venture to air a few private impressions. I am being reminded with each workshop that imagining the city of the future is a battle between dogmatic positions.

My own is no secret. I can’t see how six billion extra people can use cars the way two billion of us are using them now, without there being all kinds of catastrophes. Neither can I see why we would want an expensive, unenjoyable and unhealthy mode of urban mobility when one that is free, fun and fat-blasting could give us even faster commutes. All a city needs for its transport are six million bikes and a handful of electric carts and mobility scooters on standby for days when we really can’t pedal.

I don’t see the point of adding such a pure vision to existing cities in the way that one might add coloured ink into water. Better to let bicycling heterotopias (other spaces) be like wax in a lava lamp. Thankfully, there is enough Space Left Over After Planning (SLOAP), as well as under utilised brownfield and greyfield land in post-industrial cities, for an alternative development paradigm to thrive in the margins.

My segregationist stance reflects a range of influential texts in my own professional field: “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias” by Michel Foucault; Collage City by Colin Rowe; Queer Space by Aaron Betsky. As architects we take a perverse delight in cities of contrast.

Town planners are of a different persuasion. They would like all districts to satisfy the needs of all people. If I were to tell them that car land and bike land are like oil and water, they would say to shake them together to form an emulsion.

Those identifying as urban designers are another breed yet again. To my mind, as an architect, they have some formulaic views derived from 19th-century urban development patterns that their key authors (eg. Jane Jacobs, Leon Krier and Jan Gehl) have observed throughout Europe. I’m just as dogmatic about the need for invention, and notcopying what might have worked in a small city predating the invention of bikes.

If the fault lines dividing built environment professionals seem irreconcilable, they are nothing compared to those that separate cyclists, one from another. At one extreme are the vehicular cyclists, embarking on a right-verses-might crusade to ride in the carriageway on any road they have bought with their taxes too. Until a decade ago they presumed to speak on behalf of all cyclists. But then surveys began to reveal that they only spoke for around 1% of the population. Nearly two thirds of all people would like to ride bikes for their transport, and have even bought a bike with that intension, but they are waiting for the construction of routes that protect them from cars.

Once those routes have been built, bike mode shares increase, but not to levels where they rival the car share if parking and road networks are already in place. The best illustration of that point is Rotterdam, a city with unsustainably high levels of car use if the whole world could afford it, and with low rates of cycling—at least by Dutch standards (ref).

Rotterdam shows us that if bicycle transport is ever going to make a real difference to the health of a city’s whole population, or put a serious dint in the overall energy used to get people to jobs, then cities need to be designed to make cycling as convenient as driving has gotten to be in cities with parking garages. Unfortunately, it is often those using safe cycling infrastructure, rain hail or shine, and who make do with fowl bikes that don’t entice thieves, who object to proposals, like roofs over bike paths, or indoor bike parking, that would make cycling as easy as driving.

At least in a museum we can have these discussions. When planners and advocates of different persuasions all come together in City Hall it is to win or lose in a real contest for public space. If they meet in a university, it is to be talked down to by professors who claim to know better. Meeting in cyberspace is not meeting at all. It feels more like a park with no limit on the number of soap boxes.

Museums are different. Their collections, whether historical, critical or educational, act as triggers for the imagination to play with.

Living in Tasmania I take my kids to the Mona a lot. Free entry makes us totally indifferent, and strangely predisposed to engaging more strongly with whatever we see than if we felt we needed something back for our money. The last time I was there I found myself in a wave of conversations with my 15 year old son about immortality, the art world, mimesis and how my dad (my son’s grand dad who he never met) was a moulder. We were looking at a series of huge, expensive and improbable works by Matthew Barney. I felt like I was in a church of free thinking.

That is why I’m so pleased to be working with the NMA, QM, Angelina Russo, Daniel Oakman and of course all of the people who have donated their time to be a part of these ongoing inquiries into a possible future for cities. The city of autonomous cars, if it comes into being, will commodify mobility, consume at least as much energy and confine an already overweight society to even more chair time. It is a civic duty to imagine alternatives, and take advantage of the institutions best placed to facilitate that kind of work.